Marilyn Hardisty still remembers where she sat her final year at the log schoolhouse in Jean Marie River before her uncle moved her desk to build a stage for the students.

“The last time I went to school here, would have been December 1966,” she said. “We had a Christmas concert and I think it was one of the best Christmas concerts they ever had.”

Hardisty is part of a unique history. A story of courage when her community of Tthek’éhdélį First Nation, Jean Marie River, constructed its own school to keep the youngest children with their parents and away from residential schools.

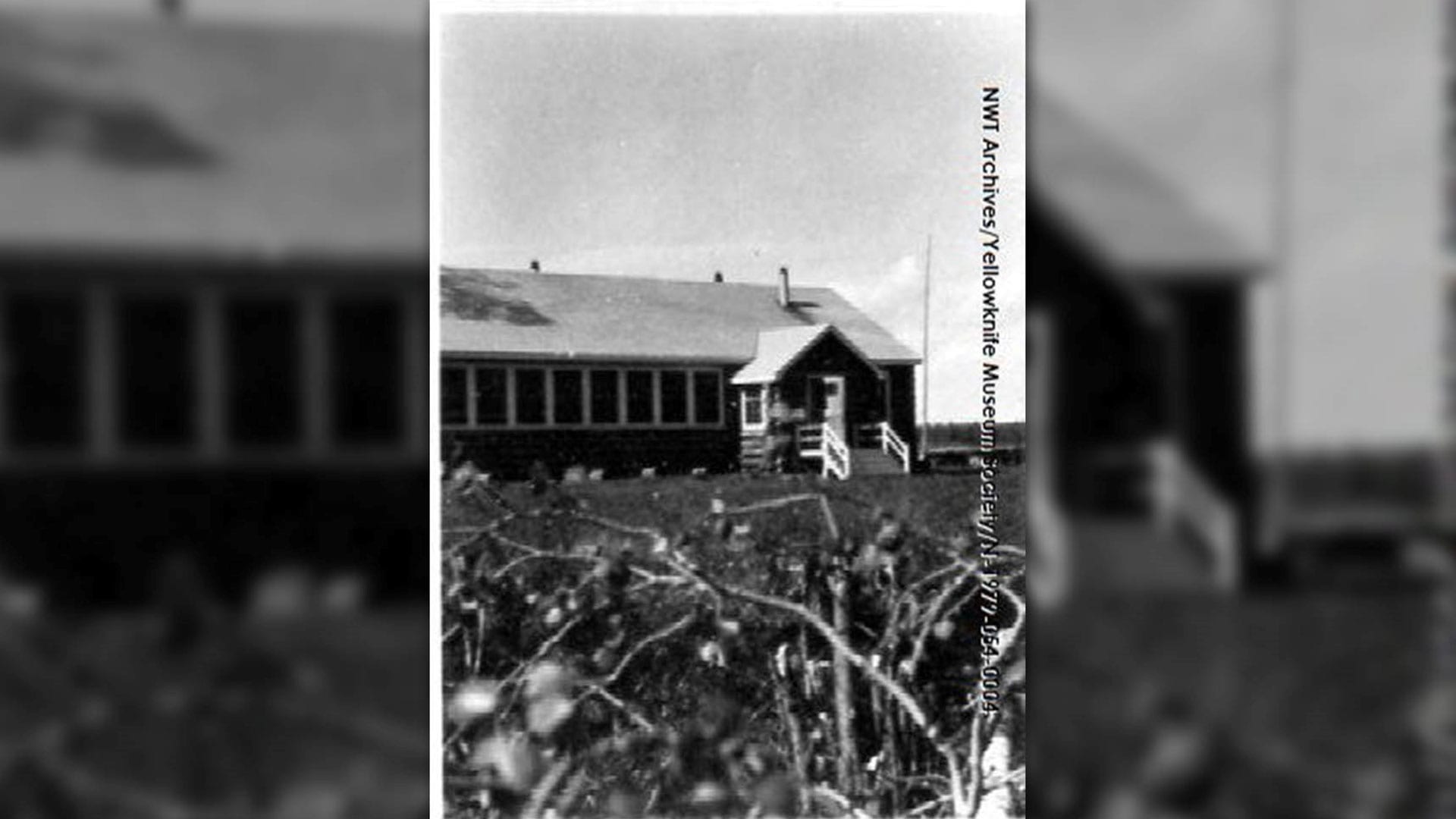

Nestled where the Jean Marie River flows into the Mackenzie River in the western region of the N.W.T., Jean Marie River was a vibrant and traditional community in the 1950s consisting of roughly 70 Dehcho Dene with lots of kids and hard working parents.

“A lot of the things they did there were with no government assistance. It was all on our own,” she said.

”They made extra money by selling logs because they had a saw mill and I believe they sold some fish in Fort Simpson.”

But when government officials did come to town, Tthek’éhdélį’s former chief Louis Norwegian refused to send kids away to attend residential school in the neighboring community of Łı́ı́dlı̨́ı̨́ Kų́ę́, Fort Simpson – a long commute by boat, float plane or dog team.

He wouldn’t settle for a federal day school either – instead he told Ottawa that the band would find a teacher and the kids would receive their education in Jean Marie River.

Norwegian worked with June Helm and Teresa Carterette, two southern anthropologists who were hoping to study northern communities.

They did just that, in exchange for the research opportunity.

Over a dozen teachers would take on the role of educating, sometimes on the banks of the river and in the schoolhouse during its operational years of 1951 to 1980.

Hardisty came from a family of eight and the school became a hub for many.

“A lot of things happened here [at the log schoolhouse] because we didn’t have a community hall. We use to have dances and movies, all sorts of gatherings here,” she said.

The school taught up to grade six and after that kids were shipped to Fort Simpson to complete Grades 7 to 9, and then either Fort Smith or Yellowknife for Grades 10 to 12.

“The biggest thing is we didn’t have to go to Fort Simpson, not right away. Until we reached Grade 7. I really appreciated the school. I was only 13, but I remember the years after that. In the fall time I just start walking around with a lump in my throat and you know the plane’s going to be coming to take you away,” Hardisty said.

Once she went off to LaPointe Hall residential school, she noted that the quality of her education degraded.

“They were more concerned with our spiritual growth than why we were there to begin with. I never remember any of the supervisors checking to see if our homework was done. We were never punished for bringing home a bad report card. Looking back I feel there wasn’t enough support given to our education,” she said.

During the 1950s and onward, the federal government and territorial government operated several federal day schools where children were educated in their own community.

Marie Wilson, a commissioner with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) spoke to APTN News about the various experiences shared through the hearing and statement gathering of survivors who did not attend residential school until a later age.

“The children who stayed home longer had a sense of home and could remember home. Many had a grounding in their language and their culture. Many of them talked to us about having had the benefit of puberty rights and ceremonial rights. Some spoke to us about knowing how to pray in their traditional way, things they have a grounding in already,” Wilson said.

Although there is no one single story of the residential school experience, the commissioner explained how critical the memory of home was for those students who stayed in their communities until they were older

“They [residential school survivors] put and sometimes talked about this; escaping in their mind to home, to a place that they could remember that was a place of peace and safety. That isn’t true for everyone. For the little ones the issue for life after residential school was really marked. Because they no longer had access to language, they’d missed cultural teachings and there was a lot of shame around that,” she said.

Part of the TRC’s 94 calls to action include commemoration and commemoration fund of the legacy of residential schools. But Wilson stressed that those projects alone were not going to be enough.

“In terms of the Jean Marie story, it’s fascinating because it isn’t really a residential school that is being upheld do we keep it or do we not? Rather, you could think of it as a building of resistance that tells a story of what happens when you have your children in your midst, in the fold, in the community and they have access to all the teachings that they have to offer,” she said.

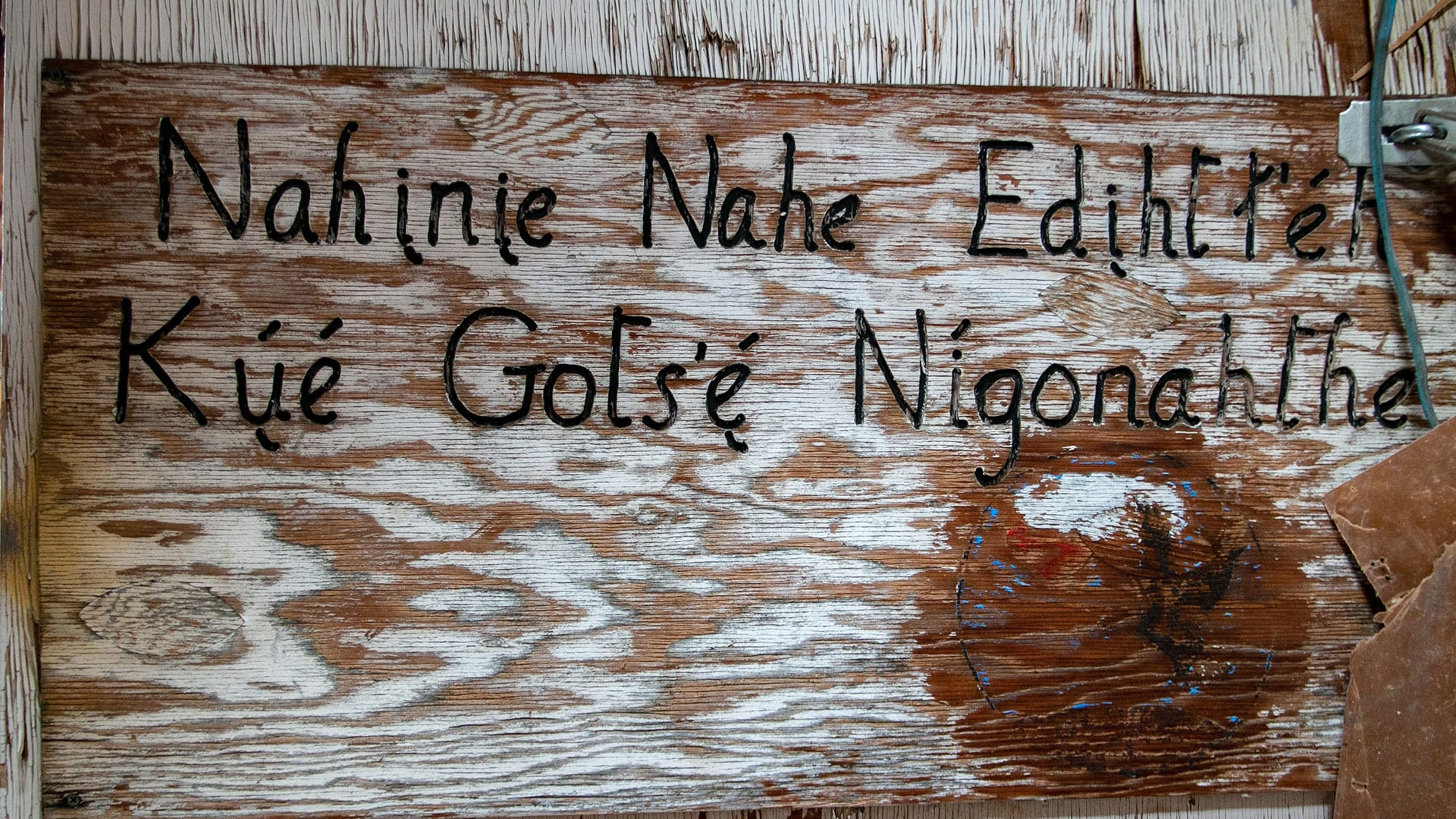

The old sign on the front door of the school house in dene zhatıé. Photo by: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs

In 2016, Hardisty decided she wanted that legacy of resistance to be part of the community’s teaching to the next generation.

The schoolhouse had stood empty for decades, but she got to work writing grant proposals and finding money through the territorial department of industry, tourism and investment and through the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency to restore the building.

“The plan was part of the building was going to be a community museum. We use to be a very traditional community at one time. Lots of people still have say dog harnesses, old traps and that kind of stuff. Then, there would be a small coffee shop and gift shop,” Hardisty said.

Stanley Sanguez, chief of Jean Marie River, said he supports the project and wants the history of his community put on display on their traditional lands and not kept housed in museums his members cannot access.

“The Canadian government wanted to know why JMR was so successful. Just before the teacher June Helm passed on I asked her what she was going to do with her if she would donate them to the Prince of Wales Museum in Yellowknife. She did. Now, when you look at those pictures it tells the richness of our community here, I hope they can come back here,” Sanguez said.

The project was placed on hold in 2018, after Hardisty had tapped into all of the money she could at that time for the project. She was only paid 10 per cent from the grants she pulled in to cover her administrative and labour costs.

But she noted should the band allocate funding for a permanent position, she would be more than willing to come back and to finish the work she had started.

“It was all our elders that built this and they are all gone now. I just want it here as a visual reminder for the next generation. The coming generations of what our people were capable of at one time. I want this to be a standing legacy to them,” Hardisty said.