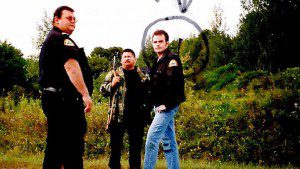

(Some of the weapons used by the First Nation police force in the botched Jan. 12, 2004, raid. APTN/File photo)

Jorge Barrera

APTN National News

Kanesatake’s post-Oka “dark time” suddenly resurfaced this week after the community’s abandoned police station was torched Monday.

The incident appears to be a response to the jailing earlier this month of four people for their role in the community’s reaction to a botched, federally-funded “illegal” raid by “an army of mercenaries” that ended in disaster more than a decade ago.

The post-Oka era in Kanesatake, which sits near Montreal, reached its nadir when 67 heavily-armed First Nation police and auxiliary officers recruited from several Algonquin and Mi’kmaq communities attempted to raid the community on Jan. 12, 2004.

The operation, which received direct funding from the Paul Martin Liberal government, ended in disaster after the raiding group became trapped in the Kanesatake Mohawk Police (KMP) station which was surrounded by angry community members and Mohawk Warriors. The officers were freed following the intervention of Peace Keepers from Kahnawake, a sister Mohawk community which sits south of Montreal.

The four men involved in Kanesatake’s reaction to the raid—Bradly Gabriel, Hubert Nelson, Allister Nicholas and Terry Yazley—surrendered to the Surete du Quebec (SQ) on Oct. 2 following a Sept. 1 Quebec Court of Appeal ruling which upheld jail sentences originally handed down by a Quebec judge in 2005, said their lawyer Dylan Roberts.

Ten days after the men turned themselves in, the abandoned KMP police station, which was the epicentre of the raid, was burned to the ground in the early morning hours on Monday. A pick-up truck was seen in the parking lot of the station shortly before it was set ablaze.

Some in Kanesatake are drawing a link between the blaze and the jailing of the four men.

“I think that the reason that the station went up in smoke maybe was to send a message,” said one community member, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Kanesatake Grand Chief Serge Simon said the majority of the community is only now learning of the sentences and it is reopening old wounds

“Since 1990, we went through hell here,” said Simon.

The 1990 “Oka crisis” was triggered in Kanesatake after the neighbouring village of Oka tried to bulldoze Mohawk burial grounds to expand a golf course.

Cabinet secrecy shrouds decision-making trail

Much remains shrouded in cabinet secrecy about the decision-making that led the Paul Martin Liberal government to transfer $900,000 to help fund the raid which was described by Jacques Chagnon, Quebec’s public security minister at the time, in a Radio-Canada interview as an “illegal” operation executed by an “army of mercenaries.”

The operation did not have the backing of the RCMP or the Surete du Quebec (SQ) because of the high risk it posed. Some of the First Nation police officers involved were not trained to use some of the high-powered weapons bought for the operation, according to records from Quebec’s Police Ethics Commissioner.

Simon said he wonders why the four men are being sent to jail when those in the Martin Liberal government who facilitated the raid continue to go unpunished.

“There is a lot of things that this community would just as soon be done with and forget about, but there are people who did some wrong and that needs to be exposed, even at the high level of the Liberal government who were involved,” said Simon. “Who is really breaking the law here? Was it the individuals who were simply defending their territories from an outside police force?”

NDP leader Tom Mulcair says, if elected, he would re-open the file to find those long-hidden answers on the Liberal government’s shadowy dealings in Kanesatake’s post-Oka era.

“The first thing we would be able to do would be to look at what was already there,” said Mulcair. “The problem of course, if you recall at the time, was that a lot of the documents were being kept secret.”

The Stephen Harper government launched a forensic audit on March 6, 2007, into what occurred in and around the time of the raid.

The Harper government, however, would only delve so deep into what happened.

The auditing firm, Navigant, was prevented from uncovering the decision-making trail because key documentation was kept out of their hands by government officials citing cabinet confidence. What the auditors did find was involvement on the file not only from Public Safety and Aboriginal Affairs (known at the time as Indian Affairs), but also by the Privy Council Office, which is the prime minister’s department and the nerve centre for the federal bureaucracy.

The auditors also discovered Aboriginal Affairs and Public Safety used police funding to back Grand Chief James Gabriel, their preferred Kanesatake band leader.

After Navigant completed its final report on April 28, 2008, Stockwell Day, Harper’s public safety minister at the time, refused to pry any further.

The issue was one of the first Mulcair championed when he entered Parliament for the first time and he called on the Harper government to launch a public inquiry into the events in Kanesatake.

“Will we ever know everything that happened? Who pulled the strings at Indian Affairs (now known as Aboriginal Affairs) to keep (Gabriel) in place? What Liberal interests were protected? Only a public inquiry can answer these questions,” said Mulcair, during question period on May 1, 2008.

Day dodged and weaved at the time saying it all happened under the Liberal government and that the Conservative government was concerned about what occurred.

Now as an NDP leader running on a platform that includes a promise to hold an inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women, Mulcair says an NDP government wouldn’t have to spend public money on an additional inquiry to uncover the real story.

“Kanesatake has continues to have serious management problems for itself and for its people and that’s not their fault. It goes back to this dark time when things really went off the rails for them so I think that is what I would do is make sure I looked at what was already there before I went through any other public expense on this,” said Mulcair, an interview with APTN National News. “I think the community itself continues to need constructive help to continue to move forward from those dark days.”

One of the targets of that raid, former Kanesatake police chief Tracy Cross, said he was “glad” to hear Mulcair committed to re-opening the issue. One of the first acts of the raiding police force in 2004 was to remove Cross from his post as police chief.

“It goes right to the top,” said Cross, referring to the Martin cabinet, Walter Walling, the Aboriginal Affairs lead on the file, and Eric Maldoff, the Liberal-appointed chief negotiator.

The Richard Walsh Affair

The 2004 incident, however, was the most explosive of a series of strange events that extended throughout most of Kanesatake’s post-Oka history.

Cross, a former Canadian Forces soldier, was also the target of an undercover operation that lasted from 1997 to 1999, that was funded by Aboriginal Affairs and run by Gabriel along with the former KMP police chief Barry Commando.

Gabriel hired a man named Richard Walsh, who had a criminal record, to dig up information on the Warriors and others in the community suspected of links to organized crime. Walsh was paid by the band under contracts for things like an underwater analysis and search and rescue training.

In 1998, posing as a KMP officer, Walsh went to CFB Petawawa and obtained Cross’ personal military file by claiming he was trying to trace the source of stolen explosives.

A year later, the OPP arrested and charged Walsh after he was found in possession KMP police uniforms, a police officer badge, warrant card, hand-cuffs and a red police strobe light. Walsh was also found with CPIC print-outs, which can only be accessed by law enforcement agents, and Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) reports. The CSIS reports were later determined not to be of a confidential nature.

Walsh was paid at least $100,000 between 1997 and 1999 for his undercover work, including $25,000 allegedly set aside specifically for the operation by Aboriginal Affairs’ negotiator on the file, according to Kanesatake band council resolutions obtained by APTN.

Many questions still remain around the Walsh affair. The Kanesatake band council has in the past called for a public inquiry specifically into this issue.

RCMP, SQ backed away from raid

But that was before the 2004 raid.

The seeds of the raid were planted in April 2003 during meetings between Gabriel, Public Safety and Aboriginal Affairs officials, according to the Navigant report. Then, in October of the same year, Gabriel requested money to “address criminality in the community” during a negotiation session on Kanesatake’s land claim. Gabriel also sent follow-up letters to Public Safety and the Quebec government asking for money claiming the situation in the community demanded immediate intervention by Canada and Quebec. A letter was also sent to the federal government’s chief negotiator Maldoff, according to the Navigant report.

That same month, Gabriel met with the RCMP and the SQ. The police agencies were not swayed by the planned operation and told Gabriel they needed more information before deciding on their role, according to an SQ affidavit obtained by APTN National News. Gabriel told the SQ and the RCMP that the operation aimed to change the KMP police chief, target the cigarette shacks in the community and “neutralize” organized crime.

In November 2004, Public Safety released $900,000 to Gabriel. The money was termed an extension to the existing funding under the community’s tripartite policing agreement. The Navigant report found that PCO and Treasury Board both approved the extra funding even though Quebec, which was part of the tripartite agreement, was not involved on the deal.

The Navigant report couldn’t determine whether Public Safety received cabinet authorization for the move.

It appears that about $62, 296 in federal dollars were used to purchase 10 M15 assault rifles, one HK MP5 SD sub-machine gun, one sniper rifle, 15 Beretta pistols and 40 Tasers which were used during the operation.

To prepare for the operation, Terry Isaac, the man Gabriel wanted to replace Cross as chief of the KMP, began trying to recruit First Nation police officers. Word began spread that something was afoot in Kanesatake and it reached the Mohawk community.

Isaac recruited officers from Listuguj, Manawan and Kipawa Eagle Village Lac Simone, among other communities.

Four days before the raid, on Jan. 7, 2004, the SQ and the RCMP told Gabriel during a meeting that they would not participate in the raid. According to an SQ affidavit, the operation had numerous problems including no identified suspects and no evidence to obtain warrants. The SQ also believed the plan carried too high a risk.

Gabriel and his “mercenary army” proceeded anyway, right into disaster.

After the 67 First Nation police and auxiliary officers entered the police station to relieve Cross, community members and Mohawk warriors surrounded the building. Kahnawake Peace Keepers, from the Mohawk community of Kahnawake which sits south of Montreal, were eventually called in to free the trapped officers.

Gabriel’s house was also burned to the ground at the time.

Several people from the community were convicted in 2005 for their involvement in the reaction to the botched raid.P

The convictions and jail sentences were then appealed while the Crown also appealed some of the acquittals. The case slowly grinded through the court system over the past 10 years, finally ending with a ruling from the Quebec Court of Appeal handed down Sept. 1 which essentially upheld the 2005 results.

Bradley Gabriel was sentenced to 12 months, Hubert Nelson received six months, Allister Nicholas received four months and Terry Yaxley three months, according to the Quebec Court of Appeal ruling.

@APTNNews