There was once a time where Germany had the world’s second-largest market for Canadian seal pelts.

Except in 2021, Germany still has an active ban on the sale, or trade, of seal products.

Twenty-six other countries in the European Union have instituted similar bans based on the long-held belief among animal activists that seal culling is an “inhumane” practice.

In a statement at the start of the 2021 Canadian seal hunt, the Belgium-based International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) said the ongoing practice is “beneath the dignity of such a progressive nation as Canada.”

Governor General Mary May Simon, who proudly wore sealskin accessories during her recent state visit to Germany, says she hopes to counter that ongoing narrative.

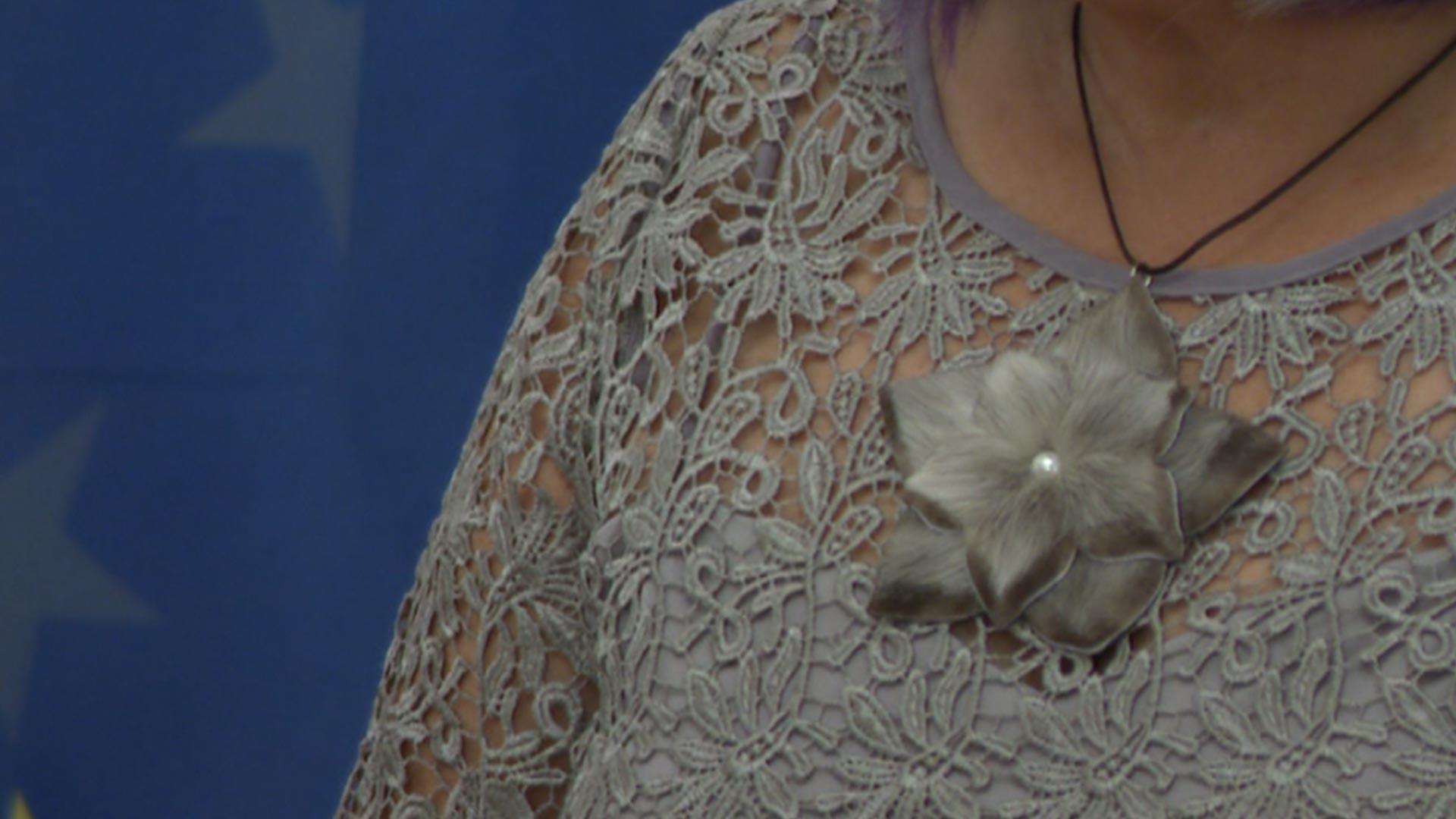

Simon notably wore an Iqaluit-made sealskin flower necklace during a black-tie dinner with Germany’s president, and again during a sit-down interview with APTN News.

“[Seal] portrays our culture and a very important part of Inuit culture. We depend on the seal for food and for many other things – and also for the fur. We use the whole animal,” Simon explained.

“When they ask me about my necklace, I get to talk about it like that – so I’m educating people in Germany about who we are, as well as learning about Germany. So it’s been a very good dialogue.”

The 2016 National Film Board of Canada documentary Angry Inuk by Alethea Arnaquq-Baril chronicles the impact of the EU’s sealskin ban on Inuit in Canada – mainly how it fuels poverty and affects international perceptions of Inuit culture.

Through their accessories, Simon and other Inuit delegates also pushed back against these misconceptions during the recent state visit to Germany – Canada’s first held in 20 years.

“We cannot adapt, we cannot start growing cows in our homeland – and we’re not going to. We’re not going to change that because another culture is telling us that we should,” said Lisa Koperqualuk, vice-president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, while wearing a beaded sealskin collar necklace.

“I really want people to know it’s part of who we are. I want it to be seen that I support our Inuit harvesters. And if people ask me ‘oh what is this made of’ and I say ‘sealskin’ and they say ‘Oh, poor baby seal’ – I say, ‘well, poor baby veal’ or ‘poor baby pig,’ you know? It’s so important for me to show that it’s part of our culture.”

While she didn’t don sealskin during her rafter-rattling performance at the Frankfurt Book Fair, Inuk soprano Deantha Edmunds – a distant relative of Simon’s – touched on the importance of fashion in Indigenous self-expression.

“I find fashion is a wonderful way to share our culture and history, and nowadays there are so many incredible Indigenous designers,” Edmunds told APTN while wearing a caribou antler and fur collar by Inuk designer Hovak Johnston of Nunavut.

“I felt grounded, and I felt like my ancestors were with me,” Edmunds added.

Simon has donned Inuit designs since the beginning of her tenure as governor general, starting with a beaded dress jointly designed by Kuujjuaq-based artist Julie Grenier, and Victoria Okpik – the first Inuk woman to graduate fashion design at Montreal’s Lasalle College.

The decision to wear a sealskin necklace in Germany continues this pattern – while also making a statement about cultural practices.

“It’s from Iqaluit, and I had a friend bring it to me because I wanted something to wear in Germany that was made from seal,” Simon explained.

“[The controversy] doesn’t stop us from showcasing it – we have always done that, and we will continue to do that.”