Pamela Freeman’s apartment is filled with photographs of her grandson Devon.

They are a memorial of a life cut too short, one filled with pain and loss but also love.

“He started to have struggles when his mom passed away and he was only six,” Freeman remembers.

“But he never cried, his only way of expressing himself was anger.

”Devon Freeman, from Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in Ontario, was diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder and struggled with mental health challenges throughout most of his young life.

When the Children’s Aid Society of Hamilton suggested he be moved to the Lynwood Charlton Centre, a group home licensed by the Ontario government, his grandmother was hopeful that he would finally receive the treatment he so desperately needed.

She still remembers the last walk they took together on the 10th anniversary of his mother’s death.

They talked about Lynwood, Devon wanted to come back home but his grandmother urged him to stay.

“I said, Devon I want you to have treatment, because it’s important,” Freeman recalls. “Prove to me that you’re going to follow this program and then we’ll go from there. And that was September 30, and I didn’t hear from him after that.”

Around the same time that Devon freeman’s body was discovered behind Lynwood, a coroner’s panel was in the process of reviewing the cases of 12 other youth that died in foster care or group homes in Ontario.

Kids who never made it out of the system like Tyra Williams-Dorey.

“She was really a wonderful soul, a wonderful human being,” her father, Nygel Dorey remembers.

“I would have loved to see the women she would have became today.

Five years down the road, a grown woman.

She passed at 17, it would be nice to see who she’d be at 22.

”Williams-Dorey was not Indigenous, but her death fits a pattern of negligence at Lynwood.

She was just 17-years-old when she was sent to the institution’s Augusta site, following multiple suicide attempts and hospitalizations.

Read more:

First Nation teen wasn’t first to die by suicide involving Hamilton treatment centre

Like Pamela Freeman, Dorey was also hopeful that his daughter would receive the care and treatment that Lynwood was supposed to provide.

What he can’t understand is why she was left alone on Mar. 2 – the day she had told her social worker at Lynwood when she was planning to end her life.

“I mean being that there was two attempts already, everybody was most definitely on high alert,” Dorey says.

“Everybody was in communication about March 2 and what may or may not transpire on March 2. I just don’t know why she was left alone that day. I really don’t know why she was left alone.”

When Dorey got the call that Tyra had gone missing on Mar. 2, he gathered as many family members and friends as he could and started searching for his daughter.

He was still out looking when police eventually found her body.

She had died by suicide and was found hanging from a tree in a small wooded area near downtown Hamilton, Ontario.

“I don’t think you can heal from something like this,” Dorey says. “I say it all the time, I would not wish someone losing a child on anybody.”

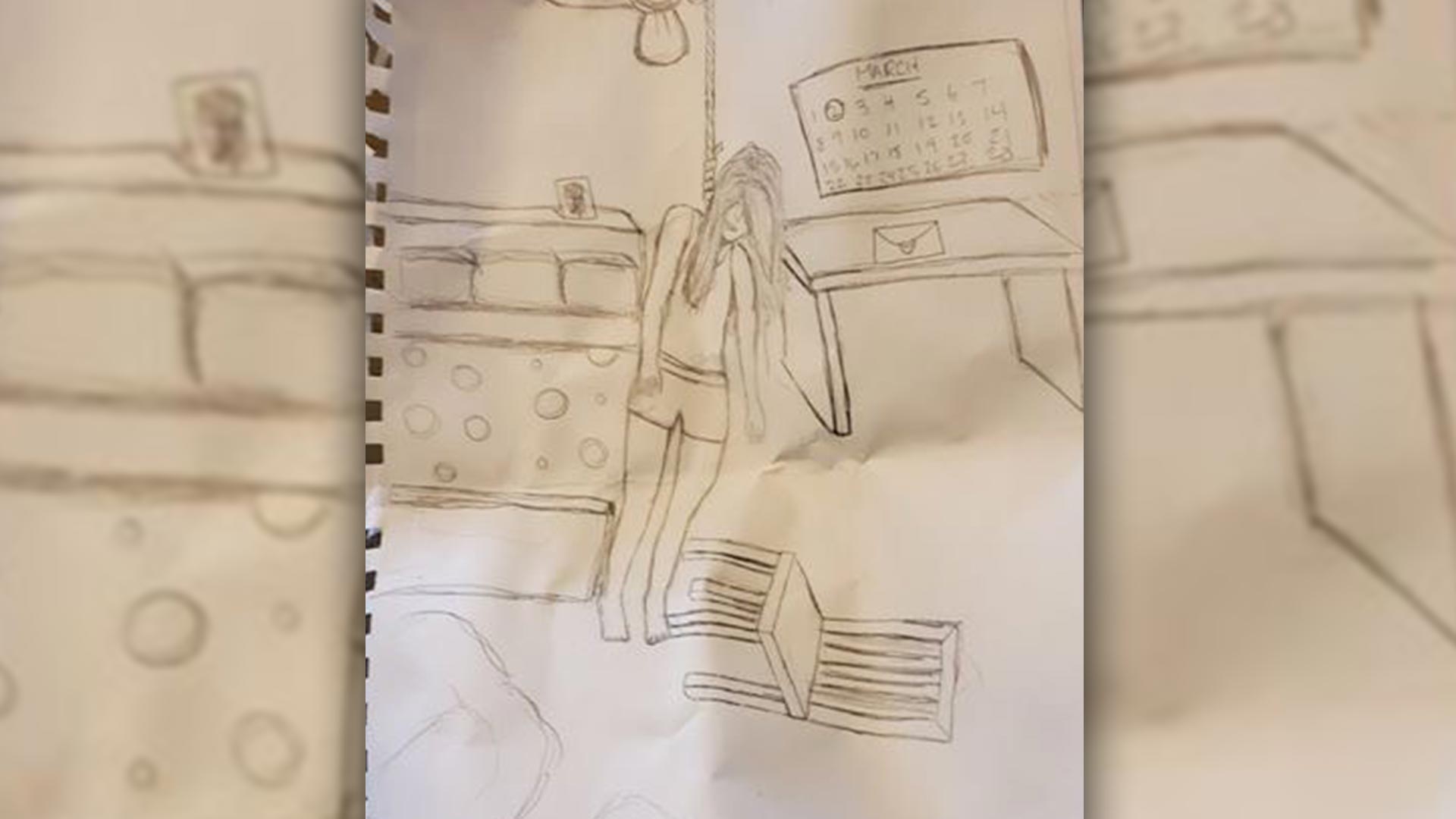

A short time after his daughter’s death, Nygel Dorey received her belongings from Lynwood.

Along with her personal items, was as a sketch she had drawn showing how she was planning on ending her life – with the date March 2 circled in the background.

What wasn’t returned to him was Tyra’s suicide note.

“I always found it odd that there was no letter,” Dorey says. “But when I asked about a letter initially, nobody knew of a letter. And I found it odd but I was like okay, if there was a letter, I’m sure it would have been returned to me in her belongings.”

It was actually Kenneth Jackson, a producer with APTN News, that discovered the existence of Tyra’s suicide note – nearly five years after she died.

The note and the fact that Tyra had told her social worker about what she was planning were both reference in her coroner’s report.

“We know this part of who we were is no longer here,” Dorey says. “Tyra was very much who I was as a person. God willing, it’s supposed to happen, that we’re supposed to go before them and they’re supposed to live on and carry our generations into the future. That didn’t happen with Tyra. I don’t wish that on anybody.

“It’s horrific, it really is.”

Read more:

Social worker knew teen was planning suicide day she died says coroner

It’s been over two years now since Devon Freeman’s body was discovered in the woods, steps away from his group home.

The tragic circumstances surrounding his death have only left his family with more questions than answers.

“The first thing that was in the paper when he was found, he was found in a wooded area, no foul play suspected,”

Devon’s grandmother, Pamela Freeman remembers.

“And I thought, how dare somebody make it seem like he wasn’t a person. Why can’t people be honest and say, yes he was on the grounds? But that wasn’t allowed to come out.”

But that wasn’t the only piece of information that was being held back.

Five months before he died – Devon Freeman made another attempt on his life, still while in the care of Lynwood.

His family was never told.

Pamela Freeman only found out about the previous suicide attempt from her lawyer, after she started pressuring the government of Ontario and the coroner’s office for an inquest into her grandson’s death.

Those types of investigations aren’t mandatory for children who die in care of the system.

“They were giving blocked out information, they didn’t share a lot of stuff,” Freeman says. “Then when she contacted me and said, did you know about him trying to commit suicide before? And I said, no I didn’t know. Why was that such a secret?

“You know, like we’re his family.”

APTN Investigates reached out to Lynwood for comment.

We wanted them to help explain the circumstances that led up to the deaths of Tyra Williams-Dorey and Devon Freeman.

Specifically why Tyra Williams-Dorey was left alone on the day she had told her social worker she was planning on dying by suicide? Why her suicide note was never sent to her family? Why Devon Freeman’s family was never informed about his previous attempt to take his own life? And how Devon Freeman’s body could have gone unnoticed for over six months, less than 35 metres away from their back door?

This is the response we received from Alex Thomson, executive director of the Lynwood Charlton Centre: “As you will know a public inquiry has been approved by the Provincial Coroner. Lynwood Charlton Centre will fully participate in the inquiry process. We anticipate that any questions will be asked and answered through the provincial inquiry.

“We continue to work collaboratively as a community to bring our resources to support vulnerable youth and our sympathies go out to the families, and all those impacted by these tragedies.”

Pamela Freeman is hopeful that the inquest will help prevent similar tragedies from occurring in the future.No date has been set.

“There’s people that need to hear this, people that are grieving, people that are in the same situation, wondering what else they could have done,” Freeman says.“All I hope for is change. Don’t make it like this child was found in the woods like nobody cared.

“Because all these kids were loved.”

I spent 17 years in the prisoner of war/foster care. When I was five I was placed on a farm, my family did not know that a week after we Cuyler kids were placed there we were suppose to be returned to our parents, but the social worker hid us and we four were made wards of the state, where I spent fifteen years. I endured what no person should ever go through. When I was fourteen years old I decided I had enough and tied a noise on my lariet got up on a milk stool, placed the rope around my neck and kicked out the stool. Thankfully the rope was old and broke. My foster dad, who I love to this day talked to me about suicide.

“You may end your pain, but the pain for your family would just begin”

My foster parent, she was mean, her husband was an amazing man. I’ll never forget those words.