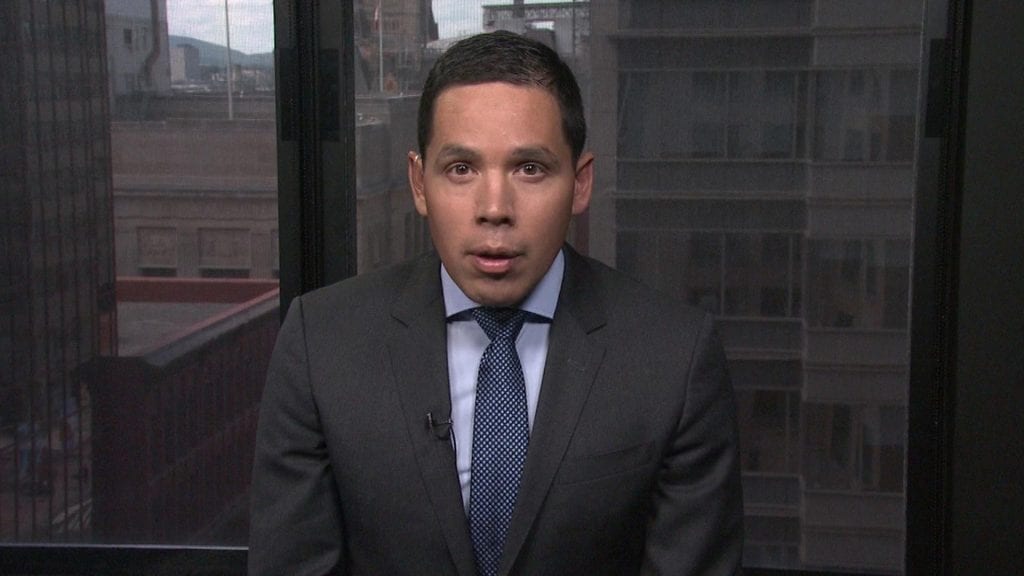

ITK President Natan Obed said governments have sat on their hands for too long and failed to address the urgent crisis of food insecurity. Photo: APTN

A new strategy from a national Inuit organization spells out a plan to tackle food insecurity in Inuit communities and calls on the federal government to address what it calls a national public health crisis.

The new document from Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, called the Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy, says 76 per cent of Inuit over the age of 15 in Canada experience food insecurity, the highest rate of any Indigenous population in a developed country in the world.

Inuit Nunangat covers 53 communities in Nunavut, Nunatsiavut in Northern Labrador, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories and Nunavik in northern Quebec.

The strategy lays out Inuit-driven solutions that it wants to see supported by all levels of government to address food insecurity and create sustainable food systems in all four Inuit regions in Canada.

“It is alarming and it’s a crisis for our communities,” Natan Obed, president of ITK, told the Canadian Press.

The strategy sets out five priorities for investment and action, including: food systems and well-being, legislation and policy, programs and services, knowledge and skills, and research and advocacy.

It also makes 33 recommendations to federal, territorial and provincial governments to address food insecurity through policies such as food programs, transportation costs and education.

Obed said the document is also meant to educate Canadians living outside of Inuit Nunangat about the ongoing food security crisis.

“They’ve probably heard of the $80 12-pack of water or the $150 turkey that sometimes makes the rounds on social media, but this strategy aims to educate Canadians on why that is,” Obed said.

One of the biggest reasons, he said, is the extremely high cost of transporting food to the North and the barriers Inuit face to accessing traditional foods.

“Just imagine if all food in all the grocery store had to be flown in to urban centres from the Prairies. Just imagine what that would be like and how much more food might be. These are things that I think Canadians should understand,” Obed said.

One of the strategy’s recommendations is to reform Nutrition North Canada “into an evidence-based food security program,” including an audit of the program.

The strategy also calls for the support of Inuit country food and harvesting systems, including harvesting infrastructure and integrating local foods into supply chains.

Poverty, overcrowded and inadequate housing, and lack of education and employment all contribute to food insecurity, the strategy says.

“The median individual income for Inuit 15 years and older in Inuit Nunangat is $23,485 compared with $92,011 for non-Indigenous people living in the region and $34,604 for Canadians as a whole,” the strategy states.

The strategy notes that Inuit food systems changed drastically starting in the early 1900s through colonial policies like settlement programs, relocation and residential schools.

The cost of living in Inuit Nunangat is also the highest in Canada, with the weekly cost of providing a healthy diet to a family of four in an Inuit community ranging from $328 to $488. The same basket of goods would cost approximately $209 in a city in southern Canada, according to the strategy.

It also highlights climate change as a threat to food security because it will make harvesting more expensive and more dangerous.

Obed hopes the federal government will allocate funding to implement the strategy, which he says many in cabinet are aware of.

Obed said ITK is finalizing an implementation plan for the strategy.

“Inuit food insecurity is not a new issue, and it amounts to a shameful human rights violation that Canada is legally obligated to remedy. Governments have stood by for far too long, prioritizing incremental actions and investments that do not remedy the root causes of food insecurity,” Obed said