The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) says it plans to push for “fisheries reconciliation” after a federal court judge ordered a judicial review of a decision by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) to transfer fishing licences off the coast of Nunavut to a non-Inuit company.

DFO’s decision came after a Jan. 26, 2021 request from Clearwater Seafoods, which was in the process of being sold to FNC Quota – a consortium of seven Mi’kmaq communities in Nova Scotia – and Premium Brands (PB), a company in British Columbia. The deal included the transfer of the fishing licences it held in Nunavut to FNC Quota.

After a series of consultations, DFO officials recommended then minister Bernadette Jordan approve the transfer.

On July 16, 2021, she made it official.

Shortly after, QIA and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI), two organizations that ensure the treaty rights of Inuit are protected, opposed the transfer claiming the minister didn’t take into account Article 15 of the Nunavut Agreement, a treaty signed by Canada and Nunavummiut in 1993.

The Article requires “special consideration be given to the principle of adjacency and the economic dependence of communities in Nunavut when allocating commercial fishing licences within Baffin Bay and Davis Strait.”

The application for judicial hearing was heard in October 2023.

In his April 26, 2024 ruling, Justice Paul Favel agreed, in part, with QIA and NTI, saying there were “four main reasons” the DFO decision was “unreasonable” when taking into consideration the Nunavut Agreement.

“The Minister failed to give special consideration to the principles of adjacency and economic dependence by not recognizing that without the reallocation of at least some of the Clearwater licences to Nunavut fishers, Nunavut interests are unlikely to gain access comparable to other provinces due to the permanent nature of these licences,” Favel wrote.

The minister “failed to give special consideration to the principle of economic dependence of Nunavut communities on marine resources, despite the significant annual landed value of the Greenland halibut and Northern shrimp fisheries,” he continued.

“This landed value is significant in the context of the smaller Nunavut economy relative to the economies of other provinces.”

Richard Paton, assistant executive director of Marine and Wildlife Conservation at the QIA, told APTN News none of Favel’s conclusions were new to Inuit.

“It has been an ongoing issue to which Inuit have continually raised,” Paton said. “That line of thinking around prioritizing where quota goes to and where it stems from goes back to the early 1990s. There was the creation of what was the Northern Turbot Development Program, which on part of the turbot created significant opportunities for southern Canadian companies to get involved in fisheries in adjacent [Nunavut] waters and excluded Inuit for the most part.

“And that’s the line of thinking the department has been one of which they’ve maintained over the last three decades.”

In his 42-page ruling, Favel said Jordan “inappropriately prioritized” a commercial fishing deal over Inuit treaty rights and “failed to grapple adequately” with whether giving the consortium the licences would hamper Canada’s obligation to “promote a fair distribution of licences” and recognize the monetary value of the stocks off Nunavut.

Commercial fishing and the principles of adjacency

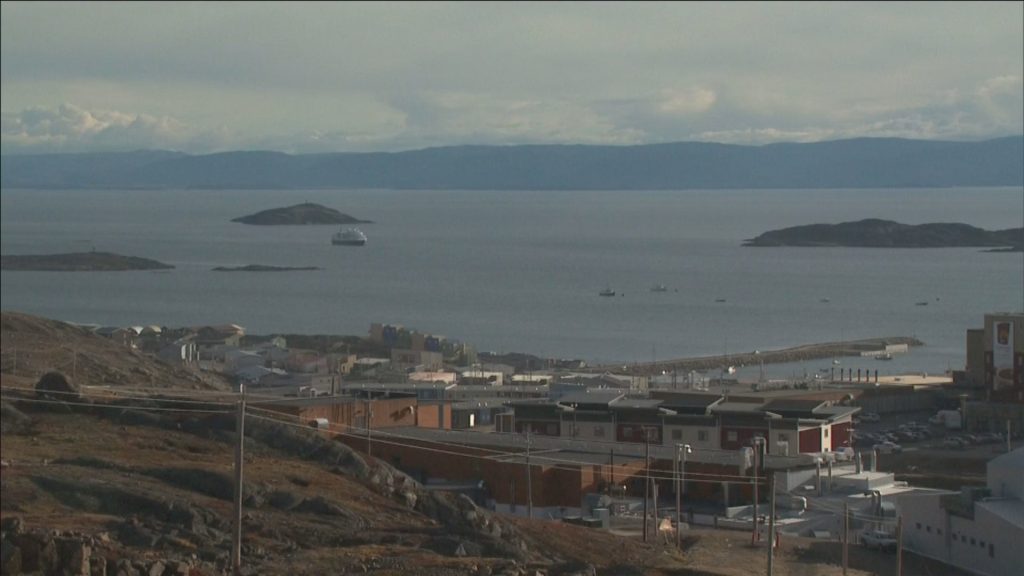

The eastern portion of Nunavut is called the Qikiqtani Region. On a map of Canada, the region includes Baffin Island and the islands that progress northward to the tip of Nunavut taking in what most people know as the top of Canada.

Thirteen of Nunavut’s 25 communities and most of the territory’s population are in this region.

The disputed licensing area is off the coast of Baffin Island.

In the world of commercial fishing in Canada, all the waters off the three coasts are broken into “zones.” Off the eastern coast of Nunavut are Zone I and Zone ll which contain Zones 0A, 0B, 1A, 1B down to 1F.

The zones are in the waters of the Davis Strait, a part of the North Atlantic Ocean that runs north along the Labrador coast before being sandwiched between Nunavut and Greenland and into Baffin Bay.

Commercial fishing is heavily regulated in Canada. Companies or individual fishing ventures need to buy a licence to harvest different kinds of fish in each zone. DFO is responsible for issuing and regulating the licences.

These licences can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars or even millions depending on the zone and species being fished. That doesn’t, at times, include the cost of boats and crew.

In this case, Clearwater asked the minister to transfer its licence for Greenland Halibut, also known as turbot, and two of its licences for northern shrimp, according to court records. All three licences permit fishing in zones off the coast of Nunavut.

Here is where the challenge comes in.

There is also something in Canada known as the principle of adjacency. That’s where the community closest to the resource has priority in terms of licensing and economic benefit. In Nunavut, and especially in the Qikiqtani Region, Nunavummiut haven’t been on the winning end of that principle.

Nigel Bankes, a retired law professor at the University of Calgary, worked with Tunngavik Federation of Nunavut, the predecessor to the present day NTI. In the 1980s and ‘90s, he helped develop the Nunavut Agreement.

“Justice Favel is not saying the transfer should never have happened, he’s simply saying that you [the minister] need to do a better job of showing how you gave special consideration to these principles in making your decision,” said Bankes, “so the minister, she or he, has got the opportunity to be redo the job, even if there is no appeal.”

Bankes said one of the issues is that southern companies have been fishing in Nunavut waters for a long time.

“I think like much else in this area it’s all history and when this turbot fishery developed in the 1970s and 1980s Inuit didn’t have the capital, didn’t have the vessel to be able to engage in that,” he said, “so the licences were allocated to both international specialists from Spain, Portugal, and another countries and also to Atlantic provinces.

“Once they’ve been allocated … it was kind of a presumption of entitlement. And that is what Inuit of Nunavut have been fighting against for 30 years.”

According to QIA, Inuit hold approximately 38 per cent of the shrimp fishery in the region. On the Turbot side, Paton said Inuit have 100 per cent of the fishery in the northern zone but the “majority of that fish is not fishable today in a sense that the majority of that area is continually covered by ice.”

“In total we have about 76 per cent of turbot in adjacent waters and 38 per cent of adjacent shrimp in those waters,” said Paton. “What Inuit are seeking is simply a fair process that outlines an equitable distribution of the fishery and we have, as our stated goal, (is) achieving parity with other Canadian jurisdictions.

According to a report by QIA, the fishery in Nunavut is an “underdeveloped pillar of the Nunavut economy” and Nunavummiut have lost out on $1.4 billion in economic benefits since 1993 when the Nunavut Agreement was signed.

“The result of the analysis revealed that significant direct and indirect economic benefits for Inuit are being lost,” said the report. “These economic losses are likely to extend into the future if there is no change in approach and decision making in Nunavut’s adjacent waters fisheries quota by the Federal Government.”

Is the Mi’kmaq consortium’s ‘leading global position’ in the seafood world in limbo?

It was a big deal.

On Jan. 25, 2021, PB and FNC Quota announced the purchase of Clearwater, the largest seafood company in North America. PB and FNC each had a 50-50 share in the company.

According to quotes from Membertou First Nation Chief Terry Paul at the time, the purchase is the “single largest investment in the seafood industry by any Indigenous group in Canada” and catapults “First Nations into a leading global position in the seafood industry.”

The price tag? A cool $1 billion.

To raise part of the money needed for its half of the purchase, FNC Quota turned to the First Nation Financial Authority (FNFA), an independent agency that provides “First Nation governments investment options, capital planning advice, and perhaps, most importantly, access to long-term loans with preferable interest rates.”

“FNFA has approved a $250 million loan to the Mi’kmaq First Nations Coalition to purchase Clearwater’s Canadian offshore fishing licenses,” said a Nov. 10, 2020 statement from FNFA. “Under the announced agreement, the First Nations will receive contractual revenues on a quarterly basis from Clearwater which will have a significant impact by creating revenue and boosting their economies.”

The transfer of the $250 million licences played a large role in the deal, as noted in Favel’s decision.

“The Transaction required completing the Licence Transfer, including transferring the associated quota from Clearwater to FNC Quota,” Favel wrote. “The Mi’kmaq Coalition financed its contribution through the First Nations Finance Authority [FNFA] which required collateral.”

FNC Quota argued as much at the October hearings in Iqaluit.

The “Minister’s refusal to approve the transfer of licences would have a far more devastating impact on the Mi’kmaq Coalition’s prospects of achieving economic justice than its approval would have on the Applicants’ preferred method of increasing its share of adjacent quota,” the consortium argued.

APTN requested an interview with Paul about the judicial review and FNC Quota’s financial share in Clearwater. APTN received a statement instead.

“At this time, we are still reviewing and further understanding the decision,” said the statement. “With recent industry transactions, we’re confident in our valuation, and this doesn’t impact the Mi’kmaq’s ownership in Clearwater.”

APTN also reached out to FNFA regarding the loan it made to FNC Quota.

The FNFA was born out of federal legislation called the First Nations Fiscal Management Act of 2005. It’s not a Crown corporation or agency of government, however, it does receive federal money.

Since 2017 it’s received $91.4 million in public money as mandated through the act according to the federal government’s website. According to its 2023 annual report, the FNFA has financed $1.8 billion in loans to 85 First Nations who are members.

When contacted, FNFA wouldn’t speak about Favel’s ruling or the implications for FNC Quota.

APTN also reached out to DFO for comment.

“After a thorough review of the Court’s decision, DFO will not appeal this decision,” said a spokesperson.

Patton said QIA plans to keep talking about the issue. He said because of Favel’s ruling, “the fish on hand cannot be used in any way during the upcoming season until such time as a redetermination and reissuance of the licenses and a decision on that is made.”

“(QIA is) seeking opportunities to connect with [DFO] Minister [Diane] Lebouthillier that will allow for that discussion to be had on the factors that give special consideration to Inuit in adjacent waters,” he said.

“The next step in our process is to advance fisheries reconciliation with Inuit in the Qitiqtani Region.

APTN asked DFO if there was a timeline for completion of the review by the minister. A spokesperson said the department is looking into it.

Editor’s Note: Richard Paton was originally credited as president of QIA. His title is assistant executive director of operations and benefits. QIA’s president is Olayuk Akesuk. We apologize for the error.