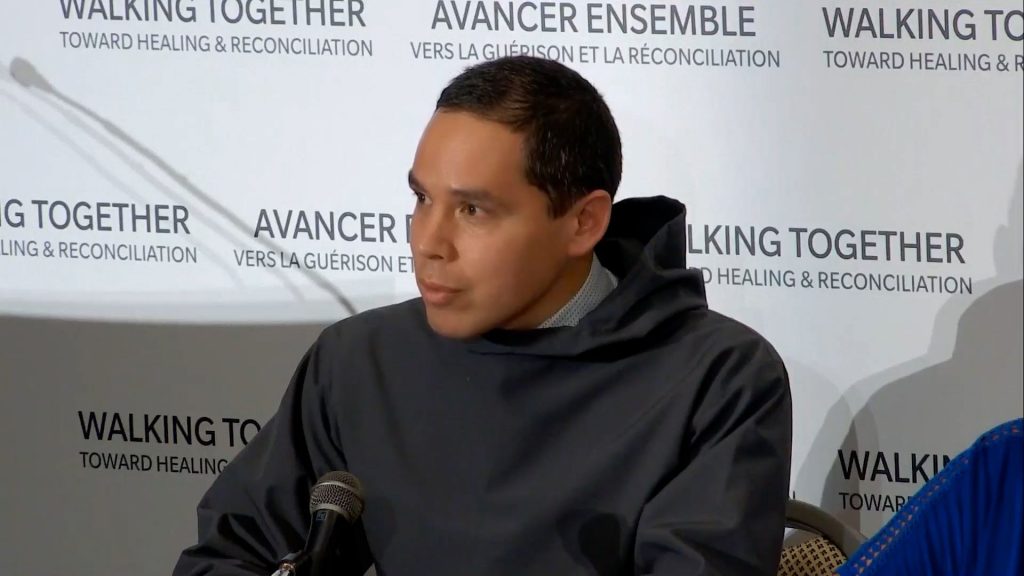

The Inuit Nunangat Policy will guide federal government officials in their dealings with Inuit across their traditional homelands. Photo: APTN

Whether in Nunavut, his home region of Nunatsiavut, or now in Ottawa as president of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Natan Obed has spent his career sitting across tables from federal politicians and their bureaucrats.

He’s worked with many who’ve expressed keen personal interest in understanding the Inuit world.

“But then I’ve also experienced and witnessed many departments or many individuals that just didn’t necessarily care,” said Obed in an interview, “or understand the Inuit reality in relation to First Nations or Métis.”

It’s this lack of understanding that Obed, now in his third term leading the national advocacy organization, hopes the Inuit Nunangat Policy, which was endorsed formally by Inuit leaders and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during a Thursday meeting in Ottawa, fixes.

“My experience has been spotty in that we can get very far with specific departments and specific ministers or specific deputy ministers who are willing to understand,” he said, “but there has not been an obligation to understand within the federal public service in any co-ordinated way, and this changes that.”

The policy recognizes the Inuit homeland, or Inuit Nunangat, as a distinct geopolitical space that comprises roughly a third of Canada’s landmass and 70 per cent of its coastline. Inuit Nunangat consists of 51 communities spread across four regions which are covered by five modern treaties or land claim agreements.

The regions are Inuvialuit in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik in northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in northern Labrador. The policy applies government wide across some 30 departments and agencies and will guide the design, development and delivery of policies, services and programs.

It’s intended to be “transformational” while supporting modern treaties and helping implement Inuit rights as laid out in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Sec. 35 of the Canadian Constitution, according to the federal government. It comes with $25 million for implementation.

The Canadian government is often accused of making high-profile aspirational pledges then failing to deliver, something Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller hopes the policy helps rectify.

He told APTN News it’s intended to bring the behaviour of government officials in line with their political masters’ lofty rhetoric.

“We’ve been good over the years and as a country in making promises or setting principles and then often shying away from those, and that’s sort of characterized our history,” said Miller in an interview. “This is a policy that is designed to outlive politicians and to make sure that the civil service is accountable to it.”

Miller agreed with Obed that a lack of a coherent framework has hindered Inuit-Crown relationships and forced Inuit leaders to spend too much time giving government officials crash courses in basic facts — for example, that Inuit aren’t, and never were, subject to the Indian Act.

“Whether it’s defence, whether it’s fisheries, (the new policy) cuts away that time that the Inuit have spent educating ourselves about our own agreements we’ve made towards them,” Miller said. “Obviously, the test to that will be the implementation of that policy.”

Given it was only adopted this week, it’s unclear how it will impact grassroots people living across the Inuit territories, and Miller said he expects some roadblocks and challenges over the next year as they come up with a plan.

He said “the proof will be in the results” when asked how the policy will impact regular people’s lives, pointing to the 2022 budget allocation of $845 million over seven years for housing across Inuit Nunangat as perhaps the first major program area where the policy will be applied.

And while it governs only the conduct of the federal civil service, which is Canada’s largest employer, “the expectation will be that provinces and territories also follow those guidelines,” said Miller.

“Provincial and territorial governments are looking at this with some trepidation asking themselves what the impact will be on them,” he admits. “It is certainly something that they will have to focus on.”

Katherine Minich, a Carleton University lecturer who studies Inuit self-determination practices, described the policy endorsement as a “savvy” piece of political work by ITK and other Inuit organizations.

She explained that the federal public service doesn’t employ many Inuit and doesn’t have much of a footprint in Inuit Nunangat, and so Inuit visions of self-determination and sovereignty have often taken a backseat to “a revolving door of bureaucrats” and “revolving visions of the Arctic” that are potentially paternalistic, colonial and ignorant.

“It’s a complement, I think, to the Arctic and Northern Policy Framework,” said Minich, who is Inuk from Nunavut, in an interview. “It’s adding a layer of Inuit specificity that is a good shift for these Inuit organizations.”

One of the policy’s main elements is the regionwide recognition of Inuktut, which is the first and preferred language of the majority of Inuit Nunangat’s residents. Despite that fact, Ottawa was never obliged to deliver services and programs in that language, which changes under this new plan.

Minich said Inuit leaders and grassroots may see their visions of self-determination as more achievable in areas like, for example, Inuktut early childhood education now that the government has a comprehensive policy in place.

“Grassroots people can be so far from a policy like this, so this isn’t necessarily a bridge to the grassroots, but I don’t know if that was ever its purpose,” she said.

“It might be written more for the federal bureaucrats to coach them into understanding that self-determination cannot be assigned to Inuit, that Inuit are the ones who voice it and propel it into reality.”