Mary Jane Logan McCallum, Christa Big Canoe and Josée Lavoie – Special to APTN News

The inquest into the death of Joyce Echaquan began May 13, 2021 in Trois-Rivieres, Que.

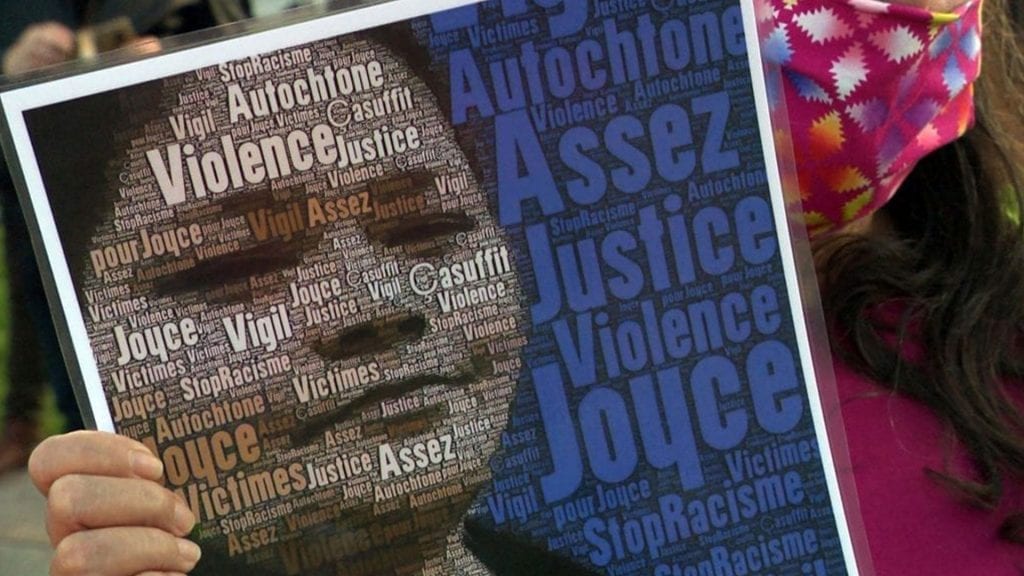

Echaquan, a member of the Manawan First Nation and mother of seven, was only 37 years old when she died at Joliette Hospital on Sept. 30, 2020 in a racist, hostile and unsafe environment.

A coroner’s inquest process is different from a criminal trial.

Whether it is a coronial or judicial process, inquests in Canada do not make findings of criminal or civil liability. The mandate of the coroner, in this case, Géhane Kamel, is not to assign blame for Echaquan’s death.

She is not a judge and she does not render a decision over the case. Rather, she will write a report that describes the probable causes and circumstances of Echaquan’s death and will make recommendations in order to avoid similar tragedies from happening in the future.

In order to write this report, she will examine oral evidence from various witnesses and experts and accept documentary reports and evidence as well. The examination is being conducted in French, with translation of Atikamekw testimonies in French, any one can watch the proceedings on a public platform.

Sherene Razack , the author of Dying from Improvement: Inquest and Inquiries into Indigenous death in custody, argues, when an Indigenous person dies in custody, the testimonies and evidence gathered centres on the deceased’s role in their own death.

Razack argues and other legal practitioners and professionals agree, that inquiries and inquests into untimely Indigenous deaths often focus their energy on blaming the descendant’s behaviour as a contributing factor to their death.

Dr. Razack explains that evidence in inquests are predominantly about the “… mental illness, alcoholic belligerence, and a mysterious incapacity to cope…” that Indigenous people experienced in life before their death rather than what action or omission occurred leading up to the death.

She argues that “the legal proceedings declare that there are no villains here, only inevitable casualties of Indigenous life.”

The biggest disappointment for Indigenous families and communities engaged in any inquest process is that the most relevant evidence rarely seems present.

The focus on toxicology, or what the Indigenous descendant did in their lifetime becomes the focal point of the process—without the benefit of the deceased testimony to explain their own story.

The system generally relies on medical evidence and third parties to address these issues instead of who did what or failed to act.

Even in this inquest, there is a ban to publish the names of some of the healthcare workers although anyone watching online will be able see who is speaking.

In part this is because the process cannot find blame but given the inquest cannot find blame, it seems unclear why some witnesses, who provided care to Ms. Echaquan are protected in this manner.

Families become frustrated with a process that is designed to find the truth and reasons for death to prevent similar future losses, but seem to miss the most obvious causes and contributions of the death.

This can be caused by focusing on science, medicine and other institutional issues instead of racism or bias that drove actions, reactions or inaction by people charged to care for them.

As far as Indigenous families are concerned the answers are often right in front of coroners, if any of them are brave enough to acknowledge that discrimination and racism were contributing factors to the death they are exploring.

Failure to recognize them in the context of these legal processes just perpetuates the long existing colonial attitudes that focuses blame on an Indigenous individuals life experiences instead of asking what steps should have been taken to stop the medical distress they were experiencing.

In Echaquan’s case, her cause of death remains unknown to the public, however we ask that as we hear the testimonies, we contextualize them in the circumstances surrounding her death – these are not unrelated.

In a significant and resourceful act, Echaquan used her cell phone to record the nurse and aide who were charged with her care, where Echaquan had a right to medical treatment.

In the video, we hear Joyce expressing concern that she was being over-medicated and that she was being given medication she has previously had negatively reacted to.

Witnesses to the video can also hear the health care providers say unspeakable racist comments that demonstrate their biases impacted their decision making ability and actions.

As we have seen in so many other cases, including that of Brian Sinclair, indifference to Indigenous suffering and life has tragic consequences.

Indeed, systemic racism in our health care system prevails. The persistent refusal to see racism as a systemic, social determinant of ill-health, perpetuates and validates racist actions that results in lack of care and death.

Unfortunately, coroner’s inquests demonstrate a similar indifference to Indigenous life when they refuse to address all forms of racism that were engaged when an Indigenous person came to their death in a circumstance like the one we all watched in horror because of Joyce’s quick thinking to broadcast her peril.

Inquests must produce concrete recommendations to prevent further deaths therefore addressing systemic racism head on is the only way to make truly impactful recommendations that can change the standards and combat the status quo.

As this inquiry began and we listened to the opening address by Ms Kamel, we are hopeful that under her leadership the results for this inquest may have a different outcome.

Mary Jane Logan McCallum, Christa Big Canoe and Josée Lavoie are members of the Brian Sinclair Working Group, which was formed in response to Sinclair’s death and the following inquest, and the questions it raised for health care, the justice system, Indigenous people and the province of Manitoba.