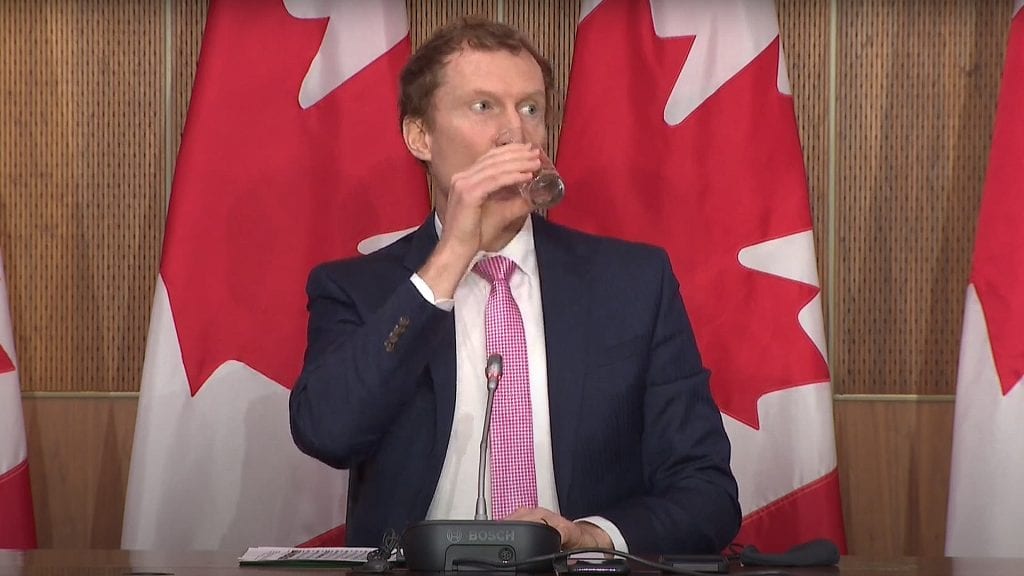

Minister Marc Miller addresses reporters at a press conference on Feb. 24. Photo: APTN

Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller sat down at a news conference on Wednesday, took off his mask and gulped from a tall, crystal-clear glass of H2O.

Light sparkled on the glass as he proceeded to rattle off cash investments and progress the Liberals have made providing First Nations reserves with potable water.

“In 2015, we made a commitment to First Nations. It was one to have access to clean and safe drinking water,” he said, “and we remain committed. We will not stop until all long-term advisories are lifted, regardless of the challenges faced in getting there.”

The water that shoots from the tap in some communities doesn’t look anything like the thirst-quenching, translucent substance on Miller’s desk.

Maybe it has an oily sheen, or a sickly brown hue. Maybe you can’t drink it without boiling, or maybe it’s best not to touch the stuff at all.

In some cases, water that is treated at a facility in a community doesn’t run to homes because no pipes exist.

Reporters promptly grilled Miller on Ottawa’s failure to supply First Nations communities the same substance that sat inches from his hand.

“Once we began the work, it became clear that transforming water infrastructure on reserves also meant confronting a large system of patchwork policies and historic underfunding,” Miller said.

“Each community has its own set of challenges. And from the beginning, we’ve worked directly with community leaders to identify and formulate the best path forward.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, during his first election campaign, promised to end all long-term drinking water advisories on reserves by March 2021.

Despite progress, the Liberals acknowledged late last year it’s a goal they won’t meet.

The minister is bracing for a federal audit of his department’s efforts on that front. The auditor general examined the matter and will table a report in the House of Commons on Thursday afternoon.

The auditor general aims to serve Parliament by providing objective, fact-based information and expert advice so politicians can hold the federal government to account for its use of taxpayer cash.

“I expect that it will reflect what I’ve noted in my own department since I came into this position 15 months ago,” said Miller.

“I’m expecting that the auditor general’s report will reflect that reality, and reflect the fact that a great deal of work remains to be done.”

That reality is stark.

The audit comes as a broad journalistic collaborative led by the Institute for Investigative Journalism unveils the findings of a thorough investigation called Clean Water, Broken Promises.

The consortium, that includes APTN News, found a systemically underfunded machine marred by questionable construction practices and long-entrenched colonial systems.

The findings suggest the constitutional division of power that places “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” under federal jurisdiction has created a racial divide.

Reserves can find themselves without clean water, relying on the feds, while neighboring municipalities under provincial authority shower in the stuff without a second thought.

The jurisdictional vacuum is a familiar one that has also created gaps in other essential services and infrastructure.

Miller acknowledged all these colonial systems make supplying reserves with clean water no easy task.

Some communities might not have the necessary infrastructure – like year-round roads – needed to support a treatment facility, he said.

Even having a state-of-the-art plant is no guarantee. The facilities require advanced knowledge in chemistry and mathematics to operate. Yet, the minister conceded, on-reserve water operators aren’t getting equal pay for equal work.

“Who’s going to blame that person for wanting to go to a community that may more often than not be non-Indigenous and make more money?”

Finally, Miller noted the government is wary of imposing solutions from above and wants to respect the sovereignty of First Nations.

“We know from decades of mistakes that the last thing we should be doing is imposing,” he said.

“The comment I hear is, ‘Give us the money and get out of the way.’ It’s something that we take to heart.”

He said Ottawa has committed to a policy shift as well as another injection of $1.5 billion promised during the fall economic statement.