There’s a Secwepemc creation story that guides Ronald Ignace as he works on revitalizing Indigenous languages across Turtle Island. It tells of a hero whose grandmother passes down the knowledge and wherewithal he needs to defeat a group of wicked cannibals.

“So he builds himself a mica shield and goes and transforms these cannibals—and lays down the law of reciprocal accountability and quiet enjoyment of the land,” Ignace said Thursday on Nation to Nation. “To me, this Indigenous language legislation is like that shield.

“No more will our children have to fear their mouths being washed with soap, or being beaten for speaking their languages or for parents or elders teaching their children their Indigenous languages. That’s what that signifies to me.”

The legislation, the Indigenous Languages Act, received royal assent in 2019. The law created the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages and gave it a broad mandate to promote, revitalize and reclaim the tongues while also educating people about them.

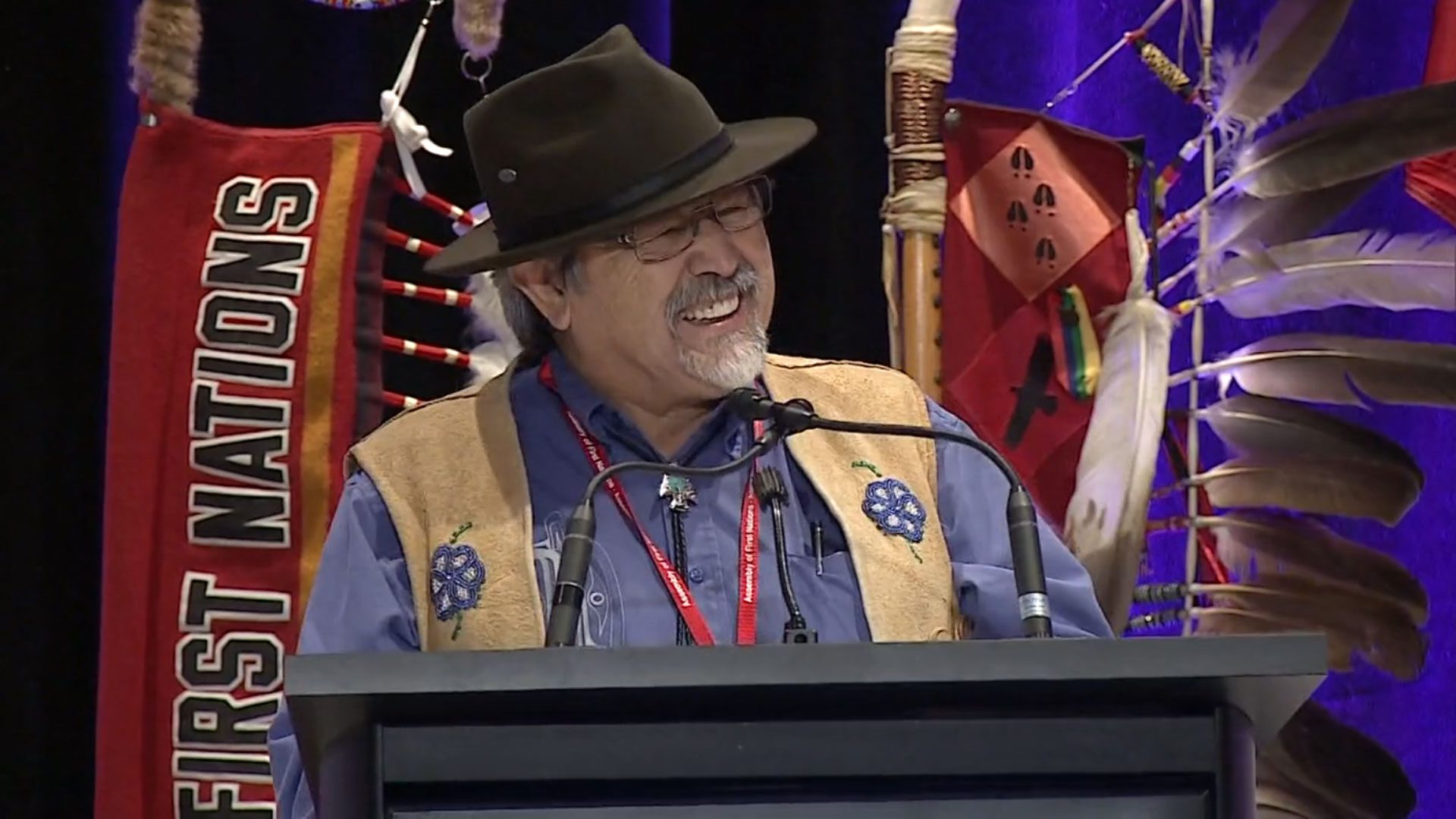

Ignace, a former 30-year elected chief with a PhD from Simon Fraser University, was appointed to head the commission in June 2021 along with three directors who have expertise in First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures respectively.

The law empowers the commission with the statutory authority to assert constitutional Aboriginal language rights, Ignace said.

That’s the mica shield. And the cannibals? They symbolize the policies of colonial erasure and assimilation the commission must transform.

The metaphor hints at the Canadian state’s deliberate efforts to destroy First Nations, Inuit and Métis as distinct peoples through a nationwide system of residential schools that operated for more than 160 years and which about 150,000 children were forced to attend.

The system aimed to “kill the Indian in the child” by attacking, destroying and devouring his or her culture just as mythological cannibals might attack, destroy and devour their foes.

They were schools only in name, and language was the first thing they assaulted.

Read more:

Canada unveils Indigenous Languages bill to fanfare, criticism

Trudeau government preparing for long-awaited Indigenous Languages Act

In the late 19th century, church and government officials formalized a policy “to rigorously exclude the use of Indian dialects” in the institutions, making English or French mandatory. Children could be beaten or whipped for breaking the rule.

Ignace himself ran away from the Kamloops Indian Residential School in 1962. Nearly 60 years later, he decided to establish the commission’s office in the old school building, thus headquartering the work of revitalizing languages in a place that tried to engineer their extinction.

“It’s an honour to be back, as the first Indigenous languages commissioner of Canada, in such a facility,” Ignace remarked.

The horrors of being in the Kamloops school were highlighted in May this year when Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc announced a ground-penetrating radar search confirmed the existence of 215 probable unmarked graves on the former grounds.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) concluded the system was a central element of Canada’s broad policy of “cultural genocide” when it delivered its final report in 2015. In its 15th call to action, the TRC urged Ottawa to create the post Ignace now occupies.

For him, language revitalization is a form of self-determination that reaffirms Indigenous Peoples’ identities as nations and their place as such within Canadian society.

“My view is that no language ought to be left behind and nor should it stand in the shadow of others,” he said. “It’s an important component of who are as a people and our rights as nations across the country.”

Because of the immensity and complexity of its mandate, Ignace said the new commission is currently in the process of laying the groundwork and trying to build a solid foundation.

“We don’t have a blueprint on which to build the commission,” he explained. “We were appointed as commissioners. Now we’re constructing the commission from ground zero.”

That includes doing a costing study. No one knows how much cash it’ll take to bring languages back from the brink. He said it requires between 2,000 and 2,500 hours of study for someone to become an able speaker. The commission has to look decades rather than weeks or months into the future.

“The systemic, colonial and racist policies that have led to the death of many of our people and the destruction of our languages and cultures is a hard, long struggle to transform,” Ignace said.

But he sounds up to the task. It certainly won’t be easy.

There are more than 70 Indigenous languages spoken across the country, and, according to UNESCO, more than a third of them are endangered.