Brandi Morin

APTN National News

With the world focusing on climate change leading up to the COP21 United Nations gathering in Paris at the end of November, some Indigenous elders in Canada say it’s an issue that they’ve been witnessing unfold for decades.

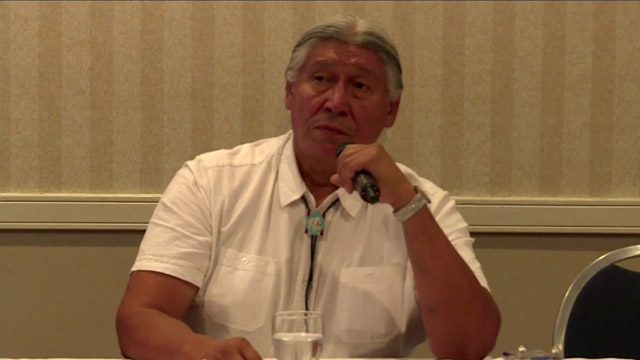

Francois Paulette from Smith Landing First Nation in the Northwest Territories (NWT) has been speaking out about changes to the landscape in his home territory.

“The north is a very sensitive, delicate place with impacts from pollution to the air and water,” said Paulette.

It’s something he said that is happening in his own backyard and becoming more noticeable.

“I live right in the bush, I can see the impacts, I can see the water changing,” said Paulette. “I can see the fish and the birds that are impacted. Even the mosquitoes, there’s hardly any this past year. What are all the birds that feed on the mosquitoes going to feed on?”

Paulette believes pollutants from the Alberta tar sands are being carried by rivers flowing to the north.

“People are starting to find fish around here that are being affected. There are changes happening to our global system of life here. And it’s affecting the way of life for the Dene,” said Paulette.

This past summer Paulette noticed that the Slave River, which flows from Lake Athabasca in northeastern Alberta to Great Slave lake in the NWT, was the lowest he had ever seen it and feared that fish that normally spawn there didn’t because of that.

Climate change is showing up in the weather patterns, he continued. The ground didn’t freeze this year when the snow fell, something that is unusual for a terrain famous for its frozen deltas.

Paulette said impacts to human health are also becoming more prevalent. He works as an elder at the Stanton Territorial hospital in Yellowknife and said unique illnesses are surfacing like rare forms of stomach cancer.

He said if something isn’t done soon to curb over development and resource extraction, which he believes is contributing to global warming, a disastrous future awaits life on earth.

To help stop climate change, Paulette is joining the Indigenous delegation heading to Paris and is accredited to take part in the UN negotiations to help create solutions.

He said Canada is at a critical crossroads and governments should commit to making fundamental changes and start to move away from a dependency on fossil fuels.

“The price of oil is low. It’s not going to go up again, the creator is telling people in a very direct way,” said Paulette. “Now you have time to listen to your conscience instead of listening to oil industry and about all the job losses etc… the answers are out there.”

The Paul First Nation sits about 40 kilometres west of Edmonton on the eastern shores of Wabamun lake.

That’s where you’ll find elder Violet Poitras harvesting roots and medicines on the traditional territory of her ancestors.

To the south of Poitras and the Paul band, on the same lake, is Canada’s largest coal fired generating plant. It’s owned by TransAlta, a private company that owns power plants around the world including six generating units in Alberta. It also operates the country’s largest surface strip coal mine that covers more than 12,600 hectares.

While Alberta’s tar sands usually attracts widespread attention due to its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) the province’s electricity sector generates almost the same amount of carbon pollution according to a recent report by the Pembina Institute.

According to the report, Alberta burns more coal for electricity than all provinces combined. And releases roughly the same quantity of GHG as half of all the passenger vehicles on the country’s highways.

“It’s not good,” said Poitras, 72. “We’ve been noticing lots of changes in the plants, the animals, the birds, and the waters have been receding and disappearing, drying up. And we’re thinking the emissions from these power plants is helping with that change, making everything worse for us and everything on earth.”

Poitras said she feels that some of the younger generation has been asleep to the issue. She’s troubled by the drastic changes to the environment she’s seen developing since she was a child.

And that hundreds of years ago elders predicted the destruction of Mother Earth and changes in the land they’re seeing today.

“All of us elders that work with Mother Nature here, we worry because we’re seeing it happen. The earth is now powdery when you dig in the ground. It used to be moist, it used to be healthy and it’s not like that anymore,” said Poitras.

She said modern technology and progress is good, but worries overproduction of industrial activities like factories and corporate farming is taking its toll. She worries it might be too late for Mother Earth to recover. She watches in horror as medicinal plants are being swallowed up by foreign plants at an alarming rate.

“Everything is going, flowers, plants they disappeared, I know, there’s some shrubs that are gone and replaced by some other plants that are mysterious to us and they look ugly to us, they’re not healthy,” said Poitras.

She hopes younger generations will start to become more aware of what’s going on. That the blindfolds of easy cash, and the easy route of modern day life will come off, because ultimately material riches will mean nothing if the earth is destroyed.

A solution to saving Mother Earth is complicated, she added, but it’s important for all people to unite on the issue.

“We all need to come together. And try to find a way to stop this killing of mother earth.”

Another elder, who grew up on the land near the mountains in Jasper agrees that people need to unite to take action,

“Our people and the whole world need to come up with a plan,” said Jimmy O’Chiese, also an Indigenous knowledge teacher.

“But it won’t happen if they keep taking and taking and taking…,” he said. “We (Indigenous Peoples) always payed respects to the land. It’s very important to have that spiritual connection to the land and respect for what you take from the land. Anytime you take something you always put it back.”

Investments to the renewable energy industry is projected to sky rocket following the COP21 event.

O’Chiese said a shift to renewable technologies is a good idea, but emphasized the need to heal the remnants industrial “destruction” will leave behind.

“There’s still that healing part that has to happen,” said O’Chiese. “So now we have to figure out how are we going to do that? We can do all that stuff with renewable energy, but that doesn’t fix the destruction that happened.”

The impacts of climate change not only surface in a physical sense, but affect the culture, traditions and spirituality of Indigenous Peoples way of life, said O’Chiese.

However, a return to the original ways of being and an interconnected relationship with the earth will be key to survival, he said.

“Without our help the earth won’t be restored. It’s very important that we realize ‘hey, somethings going on here, we better balance it out.’ We have to work to bring back nature to order to the way it was.”