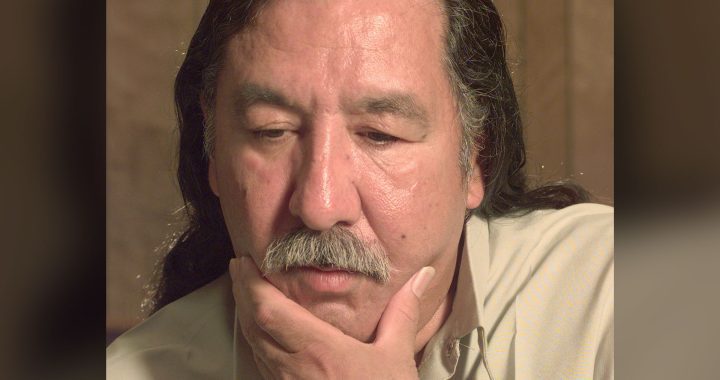

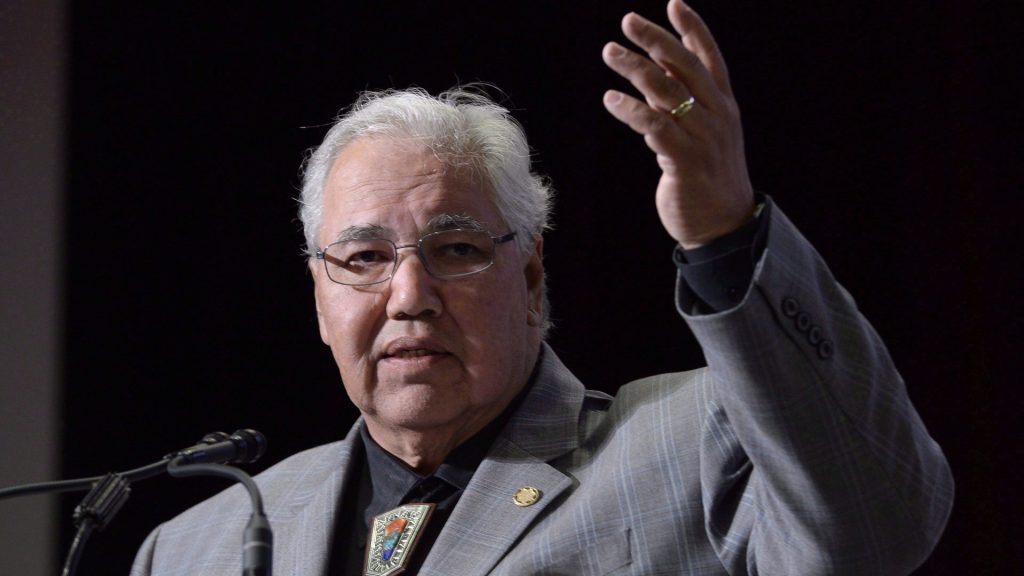

Anishinaabe from Manitoba, Murray Sinclair was a judge, senator and chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. He died Monday at 73.

His name is synonymous with reconciliation.

But Murray Sinclair, who died Monday at 73 following a lingering illness, was also a prominent Indigenous judge, advocate and leader.

“He wanted to create change,” says Sheila North, executive director of Indigenous Engagement at the University of Winnipeg and former grand chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak.

“Not only with non-Indigenous people, but also with Indigenous people.”

Sinclair was a member of Peguis First Nation and raised on the former St. Peter’s Indian Reserve north of Winnipeg. His traditional Anishinaabe name was Mizhana Gheezhik, which means The One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky.

Sinclair graduated law school from the University of Manitoba and was later named Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge, where he served in the provincial court.

“He talked about times when he was the only Indian person in the room,” recalled North, of Bunibonee Cree Nation in Manitoba. “And, he talked about the time when he would show up as the judge and the security staff were questioning what he was doing there and why he was there.

“I think, one time, they thought he was one of the accused.”

But instead of bitterness and anger, Sinclair channeled his experiences into powerful messages, whether he was steering the country through its colonial past or advising articling lawyers on racism in the justice system.

“He was a mentor,” says Harold (Sonny) Cochrane, who welcomed Sinclair as a partner at his Winnipeg-based Cochrane Sinclair law firm in 2020.

“It could be as simple as me knocking on his door and having a chat with him for a half hour in his office talking about certain legal issues,” says Cochrane, who grew up on Fisher River Cree Nation north of Winnipeg.

“He really encouraged anyone to essentially call him any time. I know many lawyers called him on his cellphone or he would come in for a particular meeting. (He) was very, very open.”

The two first met on the golf course.

“He was very, very genuine. Very wise,” added Cochrane. “He looked at things, I believe – these are my words – very equitable. Understanding there are some historical wrongs that have to be addressed but also very fair.”

Cochrane feels Sinclair, a twice-married father of five, developed that outlook from his time on the bench and in the Canadian Senate.

“He was very impartial, very fair. He was not by any means an angry individual. Very balanced.”

Patrick Deane, principal (president) of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., knew Sinclair professionally from Winnipeg.

When Sinclair was unanimously nominated as the first Indigenous person to hold the position of chancellor at Queens, Deane called him on a Saturday afternoon.

He was floored when Sinclair returned his call almost immediately.

“He told me that he has never agreed to be a chancellor at any university, but he’s been asked plenty of times,” recalled Deane. “But this was one invitation he was of a mind to accept.”

Sinclair served in the voluntary position from April 2021 to June 2024, and then agreed to stay on in a consulting role.

Deane says Sinclair delivered memorable convocation speeches.

And elevated Queens’ reputation and standards.

“He left us a very different institution,” says Deane, particularly when it came to the controversial issue of Indigenous identity of academic staff members.

“His passing is an incalculable loss.”

Sinclair was appointed to represent Manitoba in the Senate in 2016. He helped form the Independent Senators Group and sat on half a dozen senate standing committees.

“I describe him often as the type of leader who led from within,” says Sen. Kim Pate. “He inspired all of us to do the best we could, and to always remember the generations to come in everything we were doing.”

Pate says Sinclair leaves behind an “amazing” legacy that she’s sure came at a cost to his family and community.

“So thank them for that,” she says, “and (let’s) demonstrate our affection, our care and honour his legacy by actually continuing the work.”

Personally, Pate says she was struck by Sinclair’s humility.

Here was this influential force against racism and injustice who had overseen intense public inquiries into anti-Indigenous bias spreading messages of hope and joy. The recipient of numerous honorary degrees, Sinclair heard in-person the stories of roughly 5,000 residential school survivors during six years with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

The commission’s resulting 94 calls to justice showed the country how to make amends with Indigenous Peoples.

“How do you sum up a lifetime of working to ensure fairness, justice, equality (and) love for people?” Pate wondered.

North, a former journalist, says Sinclair provided counsel on everything from working in the media to calling out racism in the courts. He was co-chair of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in 1988.

“He built people up,” she says. “You didn’t feel offended you just felt educated about a truth you needed to hear.”

She remembers Sinclair phoning after she grilled a First Nations chief during a television interview.

“He said it was important to be held accountable, that leaders need to be accountable to their people.”

In private, she describes Sinclair as laid back and curious, with a sense of humour.

Kind of like a favorite uncle.

“I don’t think we’re ready to see him go. His presence with us is going to be tremendously missed and leave a void.

“He’s like no other in our community.”

Sinclair has left part of himself behind in those he inspired, and his recent memoir “Who We Are: Four Questions For a Life and a Nation”.

The book spans decades of Sinclair’s life in a series of letters written to his granddaughter, Sara Sinclair. When he became too ill to continue, his son, Niigaan Sinclair, a university lecturer, newspaper columnist and APTN National News pundit, completed it.

With files from Leanne Sanders.