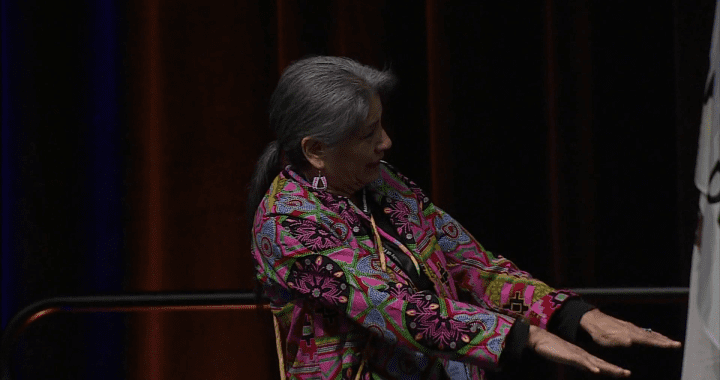

Chief Jerry Jack sits and listens to the debate on a resolution calling for a public inquiry into police in Canada on Dec. 4. The resolution passed unanimously. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN.

The chief of Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation in British Columbia says he was saddened to leave his career as a police officer with the RCMP but the racism was too much to handle.

Jerry Jack, who is attending a gathering of chiefs at the Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa, told APTN News he was an RCMP officer in B.C. for 17 years starting in 1996 but racism from some commanders and fellow officers ultimately led to him leaving the force.

“I was saddened to leave. I just felt cheated out of a career. I don’t get a pension like other officers and one of the reasons I joined the RCMP was to get a pension,” Jack said.

Jack shared how when he was starting his career, he attended an event on a reserve with his non-Indigenous detachment commander.

“We’re in this building, named after somebody, [First Nations]and he’s cussing and swearing about why they named the building after this person,” Jack said.

He said having police training and having a badge didn’t spare Jack from police-inflicted violence.

“I was in Victoria. He said to keep myself busy ‘til midnight, so I started walking around and I ended up having a cider in a pub,” Jack said. “I ended up having three or four ciders and I figured I shouldn’t drive after, so I started to walk to my room and two officers come around the corner with their lights on. They jump out and ask me what I was doing.

“They told me I scared this lady and I told them ‘I didn’t talk to anybody.’ They told me I was a liar. One of them came running up to me and punched me in the mouth. I said again ‘I didn’t talk to anybody’, and I was still speaking very calm, and he punched me in the eye.”

The officers ended up putting Jack in handcuffs and taking him into custody.

“It was scary. When I was in the force, in all the years, I never slugged anybody. I was the only one there and I knew that putting in an assault complaint wouldn’t go anywhere because police investigate their own, and they look after each other.”

Over the years, he heard other officers make derogatory comments about First Nations people saying things about them being poor, or depending on the government.

Jack said he still considers many members his friends and calls the RCMP his family. But he said he believes the systemic racism within policing hasn’t changed, especially in light of the number of deaths of First Nations people throughout the late summer and fall in police interactions.

“They (police) haven’t changed since I was in there and it’s going to take a while to change. The first problem is that they send police officers to First Nations communities that don’t want to be there, ” Jack said.

“It really shows in their work and how their attitude is when you sit and talk to them.”

The chiefs in assembly voted unanimously in favour of a resolution calling for a national inquiry into systemic racism in policing and First Nations Peoples’ deaths. The new voting system in use by the AFN does not count abstentians.

Jack is hopeful the resolution will do some good.

“I hope that it reaches the top brass. I think the [RCMP]commissioner should be here,” Jack said, “because he has to see the look on our peoples’ faces about how his officers treat our people. He’s not here-he’ll get a report, he’ll read something on paper or on a computer, but it doesn’t mean anything.”

Jack said he just had a one on one meeting with the RCMP commissioner in B.C. and told him he needed to come to his meetings in person.

“I told him ‘I want you to look into these people’s faces when they talk.’ I said it will be more meaningful and you’ll do something about it, because it’s going to affect you. And he agreed,” Jack said.

Another part of the resolution asked that immediately after a serious incident involving police and a First Nations person has occurred, that a trained First Nations person be included in the investigation. Independent investigation units in each province are often made up of retired police officers. Jack agrees.

“Because I don’t think investigations are done right [without First Nations involvement] especially when someone is hurt or killed at the hands of police, RCMP or municipal,” Jack said.

“Our people will put trust back into the system, because we don’t have that right now.”

Importance of having tribal police

For years, the issue of racism or poor service in Canadian policing has been a topic of discussion at meetings and gatherings across the country.

The current call for a national inquiry into police and First Nations people comes after 13 Indigenous people died during various forms of interaction with Canadian police forces.

Communities across the country are continuing to argue the case to develop their own police forces and not have to rely on the RCMP or in Ontario and Quebec, provincial services.

In northern Ontario, the Anishinabek Police Service patrols 16 communities around Lake Huron and Lake Superior.

Jeff Skye, chief of the APS told APTN there is an element of racism with how First Nation police services are funded.

“We are very underfunded,” said Skye. “We do not have the adequate resources to properly police our communities and it’s why we launched a human rights complaint against Public Safety Canada regarding the systemic discrimination because the issue surrounding that is all the police services in Canada are never get their funding cut.”

Skye said if communities have access to their own police services, the outcomes for dangerous calls are different.

“We lead in statistics that we have a very high crime severity index, which means our officers right across Canada… under the First Nation policing program run into some very serious crimes going on in First Nation communities because of the underfunding.

“Criminals know that and bring that criminal element to our First Nation communities.

“It is very rare First Nation service officers ever use lethal force on anybody. And it’s because we know how to deal with our people. We know we have the patience to talk to them and talk them out.”