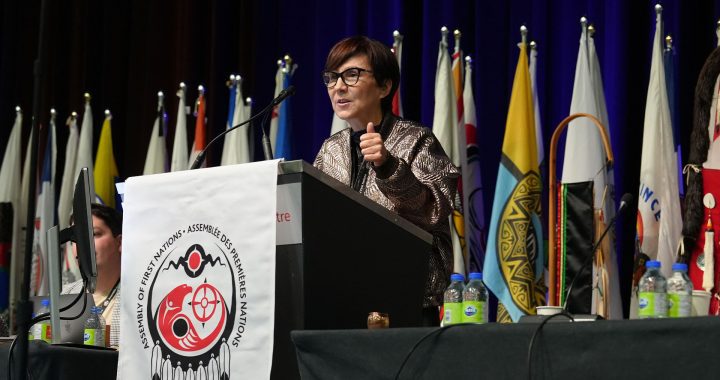

From left to right: Kevin Verch, Jordan River Anderson and Jeremy Meawasige. Jordan and Jeremy's lives made Jordan's Principle a reality for Kevin. Photo: APTN

It felt like winning the lottery – an incredible gift.

Jessica Verch was elated when she learned that, under Jordan’s Principle, Indigenous Services Canada would pay $2.8 million for a groundbreaking new drug her infant grandson Kevin Verch needs to stop the progression of his rare disease.

It was late on Jan. 8, a Friday after a hectic week. But she hopped in the car with her husband Tim and drove 45 minutes to the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation, which is about 145 km west of Ottawa, to break the good news.

“We gathered around in the kitchen area, and I asked if I could hold Kevin,” she recalled.

“Then I said, looking into Kevin’s eyes, ‘We got you your treatment, Kevin – and it’s 100 per cent covered under Jordan’s Principle’.”

Family members cried with joy. A flurry of questions followed.

“It was a really good feeling,” said Jessica Verch. “You ever hear the story of somebody winning the lottery? That was our lottery.”

Kevin, or Lil’ Kev, has spinal muscular atrophy type 2 (SMA2). It’s a debilitating neuromuscular disease that can result in weakness, paralysis or – if left untreated in its severest form – death.

Federal officials had assessed the request and approved it within 72 hours of opening the application process.

It won’t cure Kevin’s disease, but it gives him a chance at a full, normal life.

A tribute to those who came before

Securing help through Jordan’s Principle wasn’t always like this, said Cindy Blackstock.

Even five years ago, Kevin’s request might have been denied because Canada was using stricter eligibility criteria.

She said his story illustrates how over a decade of drawn-out legal battles are bearing fruit and forcing Canada to change.

“Government didn’t create change. They responded to change in the form of legal orders,” said Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

“It’s really, really important that we continue this litigation so that Jordan’s Principle becomes fully honoured – and that future governments don’t backtrack.”

Read More:

Algonquin toddler approved for $2.8M treatment through Jordan’s Principle

Algonquin community rallying behind toddler diagnosed with rare disease

She calls Kevin’s positive experience “a tribute” to Jordan River Anderson, the young Norway House Cree Nation boy whom Jordan’s Principle is named after.

Jordan was born with multiple disabilities in 1999. He died in hospital at age five – having never lived anywhere else – while Manitoba and Ottawa squabbled about who would pay for his in-home care.

“I’m glad this family got what they needed. That’s the way Jordan’s Principle is supposed to work,” said Blackstock.

“But it has to work for every single kid, and First Nations children shouldn’t still have to apply to be treated equally.”

She vows to fight as long it takes to get there.

A long fight for equality

A rejoicing Jessica and Tim Verch sat down the next day and watched Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger.

The film tells the story of Jordan’s life and the fight for equality he ignited.

It left the grandparents feeling grateful for those who battled and suffered to make the process easier. They sent it to Kevin’s parents Brody Verch and Dana Pearce to make sure they knew.

“There was a whole ton of work that we had to do to get there in those three days,” said Jessica Verch. “But nothing compared to what other families have had to battle (through).”

Jonavon Meawasige belongs to one of those families.

He knows the battle well.

The 31-year-old lobster fisherman from Pictou Landing, a Mi’kmaw community in Nova Scotia, has been battling most of his life.

His younger brother Jeremy Meawasige has hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, spinal curvature and autism. He can speak few words and can’t walk without help. He needs 24-hour care.

Jonavon had to grow up quickly, and it wasn’t always easy.

“My mom was a single mom taking care of two boys,” he said.

The round-the-clock care was consuming, and the family struggled at times. Their mom, Maurina Beadle, was Jeremy’s champion.

“My mom gave him that care all the time, even at the cost of my care – and I understood. Like, not my care, but there was a lot of things that I couldn’t do,” Jonavon recalled.

“I had to grow up and be the man of the house before I even wanted to.”

Beadle, with Jonavon’s help, cared for Jeremy at their home on Pictou Landing until she suffered a stroke in 2010.

Then the band council payed for Jeremy’s home care after Canada refused.

But the cost was steep and unsustainable. The only other option was long-term care in a provincial facility outside Pictou Landing.

The province would have covered the cost, but Jeremy would’ve had to leave his home.

Beadle and the band council took Canada to court over it and, in 2013, won. They argued that Canada’s refusal to pay the cost of in-home care violated Jordan’s Principle.

Federal Court Justice Leonard Mandamin agreed. In his decision, he likened Jeremy’s struggle to Jordan’s.

“He, like sad little Jordan, would be institutionalized, removed from family and the only home he has known. He would be placed in the same situation as was little Jordan,” wrote Mandamin.

Beadle received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for her care, advocacy and efforts to uphold Jordan’s Principle.

The battle continues

But she wasn’t done fighting.

In 2019, as his litigation guardian, she added Jeremy to a class action against Canada. She suffered another stroke a few months later. It proved fatal, and she died on Nov. 13, 2019.

Now Jonavon Meawasige is taking up his brother’s cause. He seeks to be appointed as Jeremy’s new litigation guardian so Jeremy can remain a plaintiff in the case.

Lawyers also filed an affidavit requesting Jonavon be added as a plaintiff in his own right. He would represent family members of children who were denied services under Jordan’s Principle.

“Where she left, I’m going to pick up and keep going, try to fill her shoes,” he said.

“They’re some big shoes to fill, but I’m going to make sure that Jerm’s going to be well taken care of and that he’s going to stay at home.”

Home is where Jeremy is now. It’s a place filled with childhood memories. Jonavon said he hasn’t changed their mom’s room all that much. Sometimes Jeremy will idle in the doorway, as if missing her and remembering.

Jeremy turned 26 last month. He likes to swim, visit the beach and go for cruises around town. A nursing care company looks after him full time.

But he needs a new wheelchair. His house could use repairs and upgrades like new padded flooring and handlebars on the walls to help him walk.

Jonavon isn’t certain where that money will come from. The nursing costs are covered and he’s working with Pictou Landing to figure it out.

“It’s tough. It’s on and off. There’s still that fine line: who’s paying what and who’s paying this,” he said. “There’s some things that are still up in the air. The main thing is he’s taken care of.”

There is still a chance Jeremy could have to go into a long-term care institution to receive continuing care, Jonavon said, though he’ll fight just like his mom.

“She said over her dead body, and I’m going to (as well). Over my dead body. I’m going to keep him home,” he declared.

“My community shows Jeremy a lot of love, and without that love in your community, it’s really hard.”

An evolving legal rule

Things have changed but gaps remain, said Blackstock.

In a landmark 2016 decision, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruled that Canada systematically discriminated against First Nations kids by “willfully and recklessly” underfunding child and family services on reserves and in the Yukon.

The tribunal noted that an $11-million fund provided by Health Canada to cover Jordan’s Principle costs was never accessed.

Canada was “stingy” and “interpreted away Jordan’s Principle” by using criteria that was too strict, leaving tens of thousands of kids to either suffer or be placed in out-of-home care, according to the class action documents.

Since 2016, Indigenous Services said it has committed almost $2 billion to Jordan’s Principle and approved 777,000 products, services or supports.

Canada also now acknowledges that Jordan’s Principle is not a program but a legal requirement it is obliged to uphold.

Briefing documents prepared for Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller in 2019 state that Ottawa is “legally responsible for ensuring that all First Nations children have access to the health, social, and educational products, supports, and services that they need.”

Yet Blackstock points out that Canada fought in the courts to limit this responsibility – and continues to litigate.

Canada has appealed two tribunal orders via application for judicial review.

The first ruling ordered Canada to pay children $40,000 each in damages for harms they suffered as a result of the state’s discriminatory policies. Some family members are also eligible.

Miller said they are committed to compensating but would rather do it through the class action.

Ottawa also appealed a Nov. 25 tribunal order that made more First Nations kids eligible for supports under Jordan’s Principle.

Miller said Ottawa disputes the tribunal’s authority to issue rulings on issues of identity and belonging in First Nations communities without broad consultation.

Blackstock said it’s part of the “old mentality” on Parliament Hill when it comes to First Nations.

“That’s the type of duplicity that has always been part of the government’s response to Jordan’s Principle,” she said. “They often want to take credit for Jordan’s Principle while they fight Jordan’s Principle.”

Kevin Hart, Manitoba regional chief at the Assembly of First Nations, called the court challenge a “stab in the back to us as leadership” and “a slap in the face to our First Nations children.”

In an interview with The Canadian Press, Hart called the eligibility ruling “historic” and Ottawa’s reasoning “flawed.”

He said Canada will find the AFN in court ready to fight.

Read More:

Feds agree not to fight certifying child welfare lawsuits

Remembering Maurina Beadle, the Mi’kmaw woman who fought Canada on Jordan’s Principle and won

APTN News requested an interview with Miller but he wasn’t made available. He didn’t answer directly at a press conference in Ottawa when we asked him why he disagrees with the AFN.

“We are implementing the spirit of the order, but as we have said at the very beginning of this case, we do have strong jurisdictional challenges to the authority of the court,” Miller said.

“AFN has always said that it is not a rights holder. It has advocated very forcefully on behalf of Indigenous peoples. I would invite you to ask them the same question on those particular issues of identity and belonging and not so much the ruling itself of the court.”

Blackstock fears gains could be rolled back in the future if Ottawa is successful.

“They didn’t want to implement this and make this group of children eligible, and now his (Miller’s) argument is really, ‘Trust us.’ Well, that hasn’t worked out very well for First Nations kids,” she said.

“The sign that they’re judicially reviewing it suggests that they want to overturn it.”

Jonavon watches the battle unfold with frustration and some hope.

“It was my mom’s legacy. She did a lot for it. I’m just glad that it’s starting somewhere, like people are starting to benefit from it,” he said.

“But, it’s just, why battle for it? Why do you have to keep battling? Why does the government have to keep battling for it? Why do they got to keep appealing?”

Meanwhile, activity continues behind the scenes that could eventually lead to a broad settlement for Jeremy, Jonavon and many others.

Mediation began on Dec. 10, 2020 and is expected to continue through 2021.