When Nunavut was founded, the plan was to have full Inuktitut instruction available in schools in 20 years.

It is 20 years later; and the government of Nunavut has decided to push that goal back another 20 years.

Bill 25 – the legislation to amend the Education Act – was introduced in the Nunavut Legislative Assembly in the session that ended last week.

It has received a second reading and will be up for debate and vote in the fall session, in October.

Louise Flaherty is Nunavut’s deputy minister of Education.

She won’t comment on why 20 years to achieve Inuktitut instruction was missed so badly.

“I can’t speak for why it wasn’t done, I can only speak for what we are doing now, because I wasn’t here 20 years ago,” explained Flaherty.

When asked if this same problem could be faced 20 years from now, Flaherty – who has a background as an Inuktitut teacher and publisher of Inuktitut books – says the difference this time is there are reporting requirements in place.

“With Bill 25 we have accountability on the minister [of Education] to do the reporting on the progress that is being done,” she said.

“On where we are at with the resources to achieve the language of instruction.”

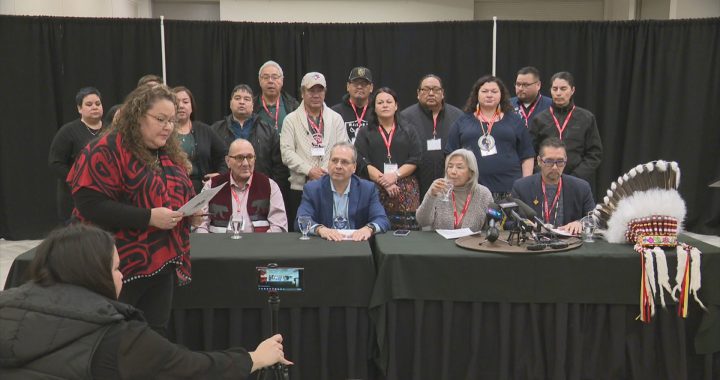

(“Teachers are still saying that they need more resources,” says Louise Flaherty is Nunavut’s deputy minister of Education. Photo: Kent Driscoll/APTN)

Alassua Hanson is a part of the class of 2019 at Inuksuk High School in Iqaluit.

She seeks out chances to learn about her Inuit culture, she is a member of the school’s drum dancing choir, and will be attending Nunavut Sivuniksavut in the fall.

That is a program where Inuit youth from across Nunavut learn about the Nunavut Land Claim.

Hanson said despite her obvious interest in all things Inuit, she didn’t learn very much Inuktitut in school.

“I haven’t had a very good experience in learning Inuktitut,” said Hanson. “Mostly because in Inuktitut classes, you’re colouring or watching movies or playing Inuit games.

“Inuit games are fun, but more learning is what I wanted.”

It’s a common complaint among Nunavut parents – kids come home from Inuktitut class with word searches or sewing, but not language skills.

One Iqaluit school didn’t even include an Inuktitut mark the last report card, because there was no teacher available to teach it.

Despite that, Flaherty disagrees with the idea that Inuktitut class has become arts and crafts time.

“I would say that is not the reality, because we have a lot of trained teachers in Nunavut, and that is not the intent and the goal or the outcome that we expect from a full Inuktitut class,” said the deputy minister.

One major problem – that both Hanson and Flaherty agree on – is a lack of resources for Inuktitut teachers.

With little direction or support, the teachers are left to design their own programs from scratch. Teaching in English, teachers can go online and find almost anything you need, not so with Inuktitut.

“I think it is because there is no knowledge of how to teach Inuktitut. Our Inuit elders need to know how to teach Inuktitut, instead of telling students to colour,” Hanson said.

Flaherty agrees, saying, “Teachers are still saying that they need more resources. They are still experiencing what I experienced as a classroom teacher, which is, a lot of the onus is given to the teacher to create their own resources.”

Nunavut Tunngavik – the representatives for Nunavut Inuit under the Nunavut Land Claim – has come out against the proposed amendments.

They say they weren’t consulted enough, and only received the final version of the bill the day it was tabled in the assembly.