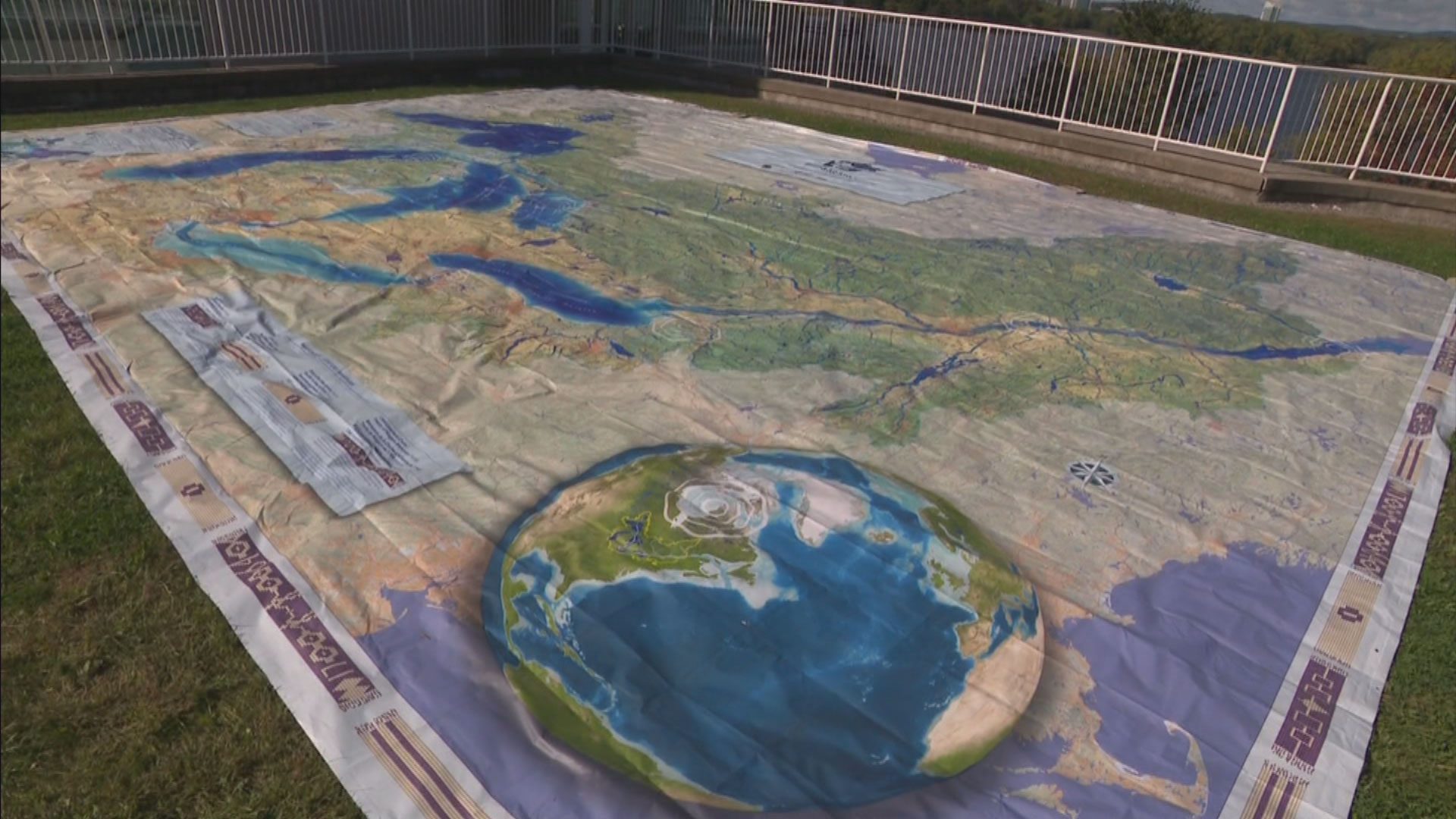

It’s the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem and also the subject of a new giant floor map that relies heavily on Indigenous knowledge.

The Biinaagami Giant Floor Map, which spans the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River watershed was unveiled in Ottawa on Thursday.

It is a collaboration between Canadian Geographic, Swim Drink Fish and Avara Media.

Biinaagami means clean, pure, water in Anishinaabemowin and Kitigan Zibi Elder Claudette Commanda told a crowd gathered at Canadian Geographic’s headquarters on Sussex Drive what it means to her.

“We are coming in with a good heart, a good spirit with kindness and love for the water,” she said. “Each and every one of us as human beings, no matter the title we hold, no matter the colour we are, no matter the creed we follow – we all come from water. Each and every one of us and we must thank the water and we must respect the water.”

Katie Doreen is the education coordinator with Canadian Geographic and she said the map is the product of extensive interviews with elders where they led the way on how the map would be constructed and what it should say.

“We weren’t just thinking up things or finding things on the internet and going to find elders to get more information out of them and share as we pleased,” she said. “We sat with the elders and it took months to build these relationships and over time we found out what was important to them and we amplified those voices in a way that was going to be guided by them.”

The map uses what’s called augmented reality meaning you can point a smart phone or tablet at different places on the map and its story will come to life on that device.

It currently contains seven different stories including ones that allow the user to swim the St. Lawrence Seaway with beluga whales, walk along the lake beds of the Great Lakes and chat with a life-sized moose at water’s edge.

Patrick Madahbee is the commissioner on governance for the Anishinabek Nation and he is also a member of the Biinaagami Shared Circle.

He said one of the goals of the giant floor map project is to share Indigenous knowledge of the Great Lakes area with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth.

“What we want to do is get out and engage with young people, especially in the schools,” Madahbee said. “Not only on the reserves around the Great Lakes watershed but in various communities – the non-Native schools. I think it’s really, really super important that people learn about our history.”

Canadian Geographic Vice-President of Learning and Reconciliation Charlene Bearhead said there are a number of things that make the map special and this includes the unique way it looks at land and water.

“We reframed the thought of territory or place or land by the waterways,” she said. “I think that’s one of the things that when you step on this (map) you can’t help but realize how significant and prevalent water is.”

The map is available to the public in a number of ways.

In person at places like the Canadian Geographic office in Ottawa, online and in lesson plans that are being made available to schools.

For more information go to the Biinaagami website at https://www.biinaagami.org/.