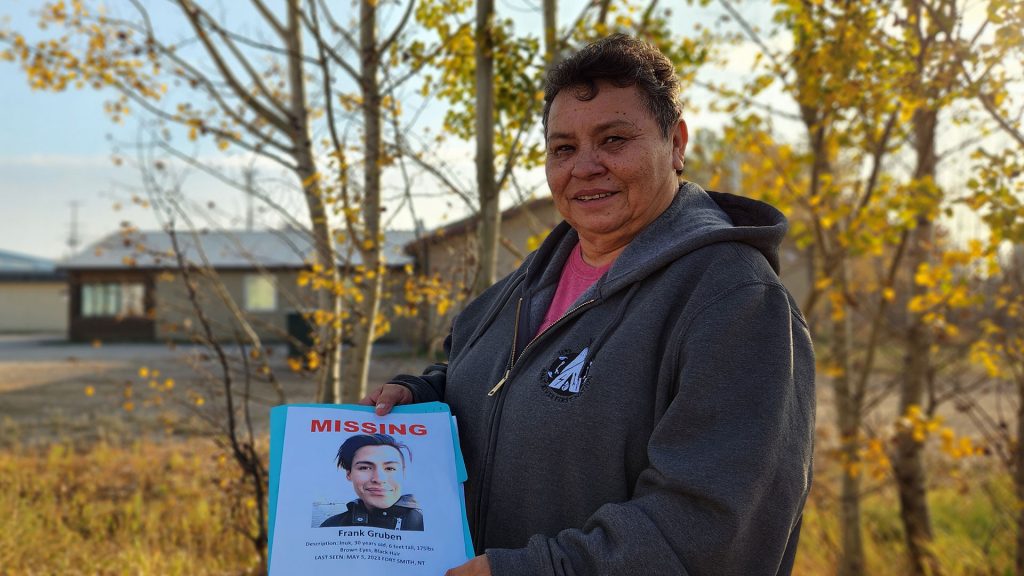

Jenny Cumming volunteered to help search for Frank Gruben. Photo: Karli Zschogner/APTN.

This is part two of a four-part series by APTN Investigates looking into the disappearance of Frank Gruben.

Fort Smith is on the Alberta border and along the turbulent waters of the Slave River. The community is situated next to Salt River First Nation and Smith Landing First Nation. On May 6, Frank Gruben went missing from Fort Smith and hasn’t been seen since.

Close by is Wood Buffalo National Park, covering almost 45,000 square kilometres, one of the largest parks in the world.

According to the Town of Fort Smith, they do not have any formal search and rescue body, but they sometimes receive support from the volunteer fire department.

On May 10, four days later, RCMP released a statement asking for the public’s assistance. Then they asked any residents who have cameras on their property to get in touch.

At that time, 11 volunteer community searches began. The search included drones and by volunteers on ATVs. A helicopter operated by the territorial government was also used to search along the riverbank.

Fort Smith’s Jenny Cumming had never met Frank Gruben but felt compelled to help.

“There was like 27 people walking in the bush, like arm length,” says Cumming. “We had people walking through the bush by the Co-Op. We also had people walking down the hill towards the riverbank behind the police station. We had people searching their yards underneath their sheds, we asked them to do it twice.”

Cumming says people from neighbouring communities also aided in the search efforts.

“We had people from Fort Resolution coming down from on the [Slave] River looking on the banks, we have people in Fort Smith searching with boats,” Cumming says.

“Knowing people in the community that are here to help us, I’m just beyond grateful for that,” says Virginia Kotokak, a friend of Frank’s who was struggling with shock and disbelief.

With local fundraising, Frank’s mother Laura Kalinek and brother Steven Gruben were able to fly to Fort Smith in the early days of the search to help out and pick up some of Frank’s belongings.

“When I had that call about my son, I knew I had to go to Fort Smith,” Kalinek says. “They were so welcoming and, in a way too, I was so scared because I did not know what I was going to face.”

Without any external search and rescue and investigative advice or leadership, community-led searches begin to dwindle. People become more frustrated with the lack of expertise and leadership.

“We had volunteers for a week and a half, maybe two weeks,” Kotokak remembers. “But at the end, it had to end because they had to go back to work.”

“I had to be there for his family, and not only that, for him. I didn’t want to stop looking for him.”

Kotokak says she also took a lead in passing on information and tips to the authorities. However, the RCMP will only provide updates to Frank’s direct family.

“We continued to search, we searched everywhere in this town, every tip, every rumor,” Kotokak says.

Cumming says there is a lasting frustration over how the investigation was handled and from the lack of formal search and rescue in the Fort Smith region.

“I’m wondering why the RCMP did not put more effort into this?” Cumming says.

Two Franks in the family’s unsolved missing cases

Frank Gruben, who is Gwich’in and Inuvialuk, is not the only unsolved missing person case for the family. Kalinek says her father, Frank Cecil Stewart, went missing from a work trip in Hay River, N.W.T. in September 1983.

“Dealing with all this just brings you back,” she says. “We never got answers for him still to this day. So, remember to always tell your family you love them. It’s so important to share that every day.

“It doesn’t cost nothing to say ‘I love you.’”

For the family, the unsolved cases of both Frank and the grandfather he never met – 40 years apart – underlines ongoing systemic injustice facing Indigenous communities.

“I think this is not a search and rescue, this is a search and recover,” says Steven Gruben. “To me, I feel like that’s genocide that’s still happening to our people.”

Ken Laviolette is an Elder and long-time tracker from the Fort Smith-Salt River First Nation. He says this is not the first time he has sensed apathy or racism from the RCMP in cases of Indigenous peoples.

“I’ve been involved with many search and rescues over the last 40 years, we’ve had a lot of issues happening here,” says Laviolette. “Before, there’s a search for one of the Elders that went missing years ago and there were rumors, saying that someone threw him in the river. He was found later in the river quite a few days later, but the cops just kind of brushed it off.

“We need change,” Laviolette continues. “I am day school, from Indian Day school, I had family [that] was in residential school. And you know, the hardship they went through is still going on with our young kids, and that’s why we lost Frank.”

He thanks all the volunteers who have made the effort to search.

“I’m so proud of the people here in the community, everybody, from all walks of life,” he says, “but we need closure for these people. We need closure for his mother, his brother and his other family.

“If you have something to share, come out and give it to us so we could find him and bring them home. Every person matters. Every child matters.”

In early July, the head of the RCMP in the N.W.T., Chief Supt. Sydney Leckey provided the media with an update about Frank Gruben’s case.

There, he said that they have not called on formal search and rescue efforts because they don’t have a specific last known location and that they don’t have the capacity.

“I don’t understand why it took so long to get something started?” says Frank’s mother Laura Kalinek. “Like if it was somebody else, how fast they would look out, get the dogs, get the Rangers.”

“[RCMP and Canadian Rangers] should be involved with this,” adds Laviolette. “They have the equipment, they have the dogs, they have their aircraft, but they don’t do nothing for them to come out.

“And now the country’s all burnt.”

A few weeks after Fort Smith’s five-week wildfire evacuation order, Fort Smith RCMP Sgt. Cagri Yilmaz told APTN that the Mounties had done their best at the start, but they do not have the mandate nor capacity in search in rescue.

According to the Canadian Armed Forces and territorial departments, the RCMP is the main authority in calling on search and rescue support other than the territorial government.

Dave Taylor, president of the Civil Air Search and Rescue Association in the N.W.T. says it didn’t receive any call from RCMP around Frank’s search.

“In the spring, I did let members of Fort Smith know what services we could provide and that RCMP should know of our services,” says Taylor in an email. “It is in [the RCMP] procedures manual that we are an available resource to consider for a missing person, and they have called us for other searches for missing persons outside of Yellowknife, including in the Fort Smith area.”

The more than 70 trained voluntary Taylor’s group are available and contracted by the RCMP, municipalities, and the military. They are available across four N.W.T. regions of Inuvik, Norman Wells, and the Yellowknife and Hay River. Taylor also points to the Alberta division, with Fort McMurray being the closest available to help.

He says while Hay River has not been operational this year due to the lack of trained volunteers, Yellowknife is active. He notes the territory has $10,000 available for community search and rescue.

“In the 23 years since we’ve had this agreement, [Fort Smith region] have never tasked us, and I suspect it is cost related,” Taylor says. “It would be $5,000 just to get us to Fort Smith and back.”

Lt. Col. Kristian Udesen is the region’s Commanding Officer for the 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group.

With 447 current CAF Canadian Rangers across the N.W.T., 19 in Fort Smith, and 23 in Hay River, either the territory’s Emergency Management Office or the RCMP are responsible for requesting ranger support for a search if they feel that they need immediate additional resources to save a life, says Udesen.

Over email, Udesen says they have no record of 1 CRPG receiving a request since Frank went missing.

For Rangers authorized approval, it needs to be delegated to Commander Joint Task Force North, or to Udesen, and can be approved if deemed that the situation is one of imminent danger.

Lessons ‘we can learn and use’ from 2018 freezing death: premier

R.J. Simpson is currently the premier of the Northwest Territories, but when Frank disappeared, he was serving as the territory’s justice minister.

Responding to the community’s search and rescue concerns, Simpson says that it’s important for the territory to re-address search and rescue responsibilities in missing-persons cases and update logistics gaps.

“I think that’s a great point that within community there needs to be a plan, not just the RCMP who do everything,” says Simpson. “I know that within the Beaufort Delta it’s much more common to have these search and rescue. So, there is also lessons from up there that we can learn and use in other communities.”

In the Beaufort Delta, the aftermath of the freezing death of Richard Binder Jr. in 2018 led to the chief coroner making 12 recommendations to the RCMP. These recommendations included ensuring the use of police dogs, reviewing their search and rescue manual, and ensuring that one or two officers are assigned to update family members during a missing persons investigation.

In the meantime, Frank’s exhausted friends and volunteer searchers in Fort Smith are left on their own.

“I just don’t want to give up on him, I’m not going to give up hope,” says Kotokak. “I’m not going to just not look for him, I need to find him and bring them home to his family, his family needs some more than ever, and he needs to be at home. I just won’t give up on that.”

Laviolette and Cumming say that even for local Rangers, they find the situation frustrating.

“We do have to start a committee in Fort Smith for something like this,” says Cumming. “We never know if it’s going to happen again. We just need to find him for Laura and Steven’s sake, we got to find him.”

Next in the series, The RCMP response and the need for missing-persons legislation

Contact Crimestoppers to submit a tip anonymously by phone at 1-800-222-8477, or online by clicking on the “Submit a Tip” button at nwtnu.crimestoppersweb.com.

You can also call the Fort Smith RCMP detachment directly at 1-867-872-1111.

If after reading this story you’d like to talk to someone for any reason, you can call the Hope for Wellness line at 1-855-242-3310.