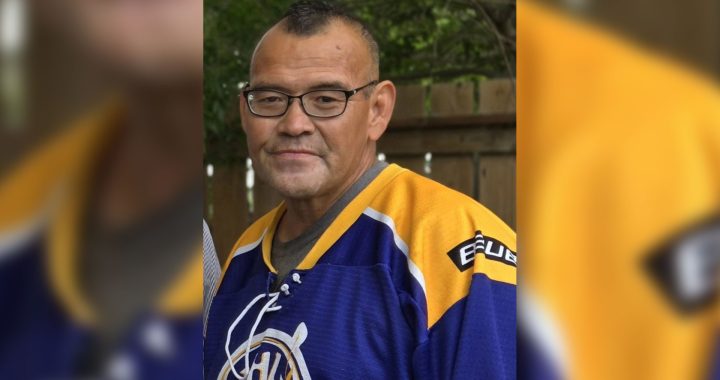

Vinnie Lillie is eager to tell his story.

Not only about how he survived prison and joined a gang behind bars – but how he got there in the first place.

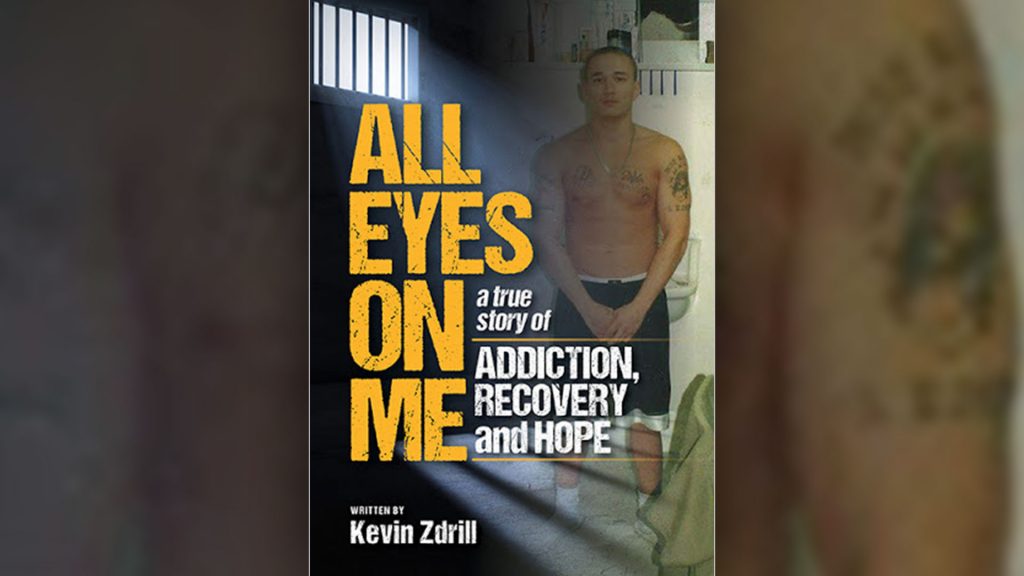

“I’m an attention seeker,” he says with a grin. “That’s why the book is called All Eyes On Me.”

In the paperback penned by Winnipeg writer Kevin Zdrill and released during the pandemic, Lillie recounts robbing convenience stores to finance a drug habit and serving three prison terms.

It’s a voice not often heard amid the clamor of advocates, politicians, police and corrections officials debating the overrepresentation of Indigenous men in Canadian jails and prisons.

“When those cell doors close at night the true people emerge,” says Lillie.

“I don’t care what you’re there for. You’re not telling yourself how happy you are about what you did to get to where you’re at in life.”

Lillie says he shared his story to inspire others, documenting his “true story of addiction, recovery and hope.”

His recovery began with a violent beat-down to escape a gang.

“I took a deep breath, walked into the middle of the room and stopped,” says Chapter 1. “My hands at my sides balled into fists, clenching and unclenching. These were the same guys from my gang – we once fought side by side defending our interests within the prison walls.

“Except today that bond was gone and they were there to deliver my gang out-beats at whatever cost to my life. I was terrified of the outcome.”

As a hemophiliac, Lillie was in mortal danger of dying. Yet he survived the requisite punishment.

Upon waking in hospital, he told the prison guard by his side: “I’m just so thankful.”

Gang members are not supposed to talk about “the life.” But Lillie shares his story as part of his recovery.

And does what’s best for him now – not the gang.

One of Lillie’s heros is Mitch Bourbonniere, a 30-year gang diversion worker in Winnipeg and head of male support group Ogijiita Pimatiswin Kinamatwin (OPK).

That’s why Bourbonniere was asked to write the book’s introduction.

“While in that life, one must become a monster and not feel,” Bourbonniere writes. “The only way to come out of that life is to start to feel again.”

Bourbonniere says young men like Lillie turn to the “shadow side” – gang life, street life, the bar scene, drug culture, prison – to get what they’re missing.

Until they figure out what they’re missing.

Lillie was the youngest of four sons who grew up in St. Norbert, a suburb in south Winnipeg. His mom is First Nations and Lillie says he is a member of Peguis First Nation in south-central Manitoba.

He was three when his dad went to jail for sexually abusing his older siblings.

“My mom called the police,” Lillie says. “She was left to take care of all of us on her own. Four of us.”

While his mom worked to support them, Lillie was introduced to street drugs by friends and at parties. He started stealing to pay for them.

He went to prison the first time at the age of 21.

Upon his release, Lillie started robbing convenience stores at knifepoint for money to buy drugs.

“I just went back into the old cycle,” he says, “started robbing stores again.

“When I’m high on crack cocaine, it’s like, I need more, and I’ll do anything for that. It’s the fuel that pushes you over the edge.”

Today, Lillie is 41 and one of the most positive people Bourbonniere knows.

‘My hero’

“Vinnie Lillie is my hero,” Bourbonniere writes in the book.

“He comes from trauma, but his beautiful soul has never dampened. I learn much from him every day.”

Lillie is now a street patrol member with the Downtown Community Safety Partnership to protect the community he says he once terrorized. He is also a youth worker, OPK volunteer, husband, father and step-father.

He says he proposed to his wife when he was still behind bars.

It was at Stony Mountain Institution, a multi-security penitentiary north of Winnipeg, where Lillie first joined a criminal gang.

He says he did it for protection.

During his second federal stint, he says he was recruited by a different gang, where his duties included beating inmates, selling drugs and collecting money owed for drugs.

He wasn’t taking crack, but doing other drugs in what he says was a super-violent lifestyle.

“That’s what [gangs] use,” he says, “fear and intimidation, violence and control over people.”

At night in his bunk he’d reflect on his life.

Zdrill, the book’s author and a former crisis intervention worker in Winnipeg, says he gathered Lillie’s story for more than a year.

‘Characteristic hallmark’

He says men like Lillie share “a characteristic hallmark…

“It is one in which emotional and spiritual pain is so often locked inside a man with a misguided belief that it is never to be discussed. No tears are to be shed. Weakness is not to be shown, and asking for help is not an option.”

When Lillie left prison a second time, he still had more drugs to do and a defining crime to commit: robbing an innocent person.

“I was blacked out on pills and alcohol and had been smoking crack that night,” he says. “I went to (a Main Street) hotel and I robbed a guy for his beer and money, and I chopped him in the head with a hatchet.”

The victim was severely injured but survived. He was a stranger to Lillie and now suffered his own trauma.

“I don’t even remember,” says Lillie. “[I left the scene] and went back to partying.”

It didn’t take long and he was back in prison.

It’s that experience – as an Indigenous man in prison – he shares with kids considered high risk – mostly boys.

Lillie says he has spoken at about 70 Winnipeg public schools alongside police officers as part of an ongoing gang prevention campaign.

He is still hoping to be invited to speak at a First Nations school.

Lillie has also spoken to military cadets, at drug treatment centres and child welfare agencies.

“I’m all about being part of the solution now,” he says. “Not the problem.”

But many people, including Lillie, say the criminal justice system never addresses why people offend in the first place.

“Drugs got me into crime, but what got me into the drugs?” he says. “People look at addicts and they want to judge them and point their finger and they say, ‘Why the addiction?’ But that’s not the question. The question is: ‘Why the pain?’

“What’s the percentage of people who are in jail because of addiction?”

Lillie chalks his 20-year history of addiction, crime and detention up to trauma.

“Seeing a lot of crazy things as a kid and, obviously, I got sexually abused (by babysitters). It became normal for me.”

He was also isolated and ostracized as a child because of out-dated views of his hemophilia.

“Ultimately, I would never take back any of the crazy stuff that I’ve been through because it’s made me who I am today,” he says. “I’ve done a lot of personal development and healing these past four years while I’ve been sober…

“You’ve got to grow through what you go through.”

Read More:

Root Causes: The inside story of Indigenous street gangs in Winnipeg