Warning: This story contains details that some people may find disturbing. The Hope for Wellness Help Line offers immediate help to all Indigenous Peoples across Canada. It is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week at 1-855-242-3310 in English and French and upon request in Cree, Ojibway, and Inuktitut.

A pigeon lands on the railing of his balcony overlooking Lyon, the third-largest city in France. It appears to be waiting for something.

Pierre Joannes Rivoire smiles.

“I feed them,” he says, but not today.

“I don’t have any bread,” says the 91-year-old as the bird gives up and flies away.

The French Catholic priest turns his attention back to the interview with APTN News.

“Come on, why are there these accusations?” he says. “I am wondering what’s the motive?”

Rivoire is referring to the allegations from four Inuit who say he sexually abused them as children while working as an Oblate missionary in northern Canada’s territory of Nunavut from 1963 to 1993.

He says it never happened. None of the charges against him have been tested or proven.

- Oblate priest Joannes Rivoire with APTN News reporter Kathleen Martens in Lyon, France. Photo: Agustin Lucardi for APTN

It is Rivoire’s first interview with a Canadian news outlet in more than a decade. He agreed in a series of emails to speak on camera for television and then changed his mind.

Without prompting, he says he hates the media.

Coverage of the alleged historical abuse crimes has led to estrangement from his family in Rontalon, a village about 30 minutes from Lyon.

“The press is terrible,” he says, tapping his finger on the computer desk. “They can launch anything.

“…Things get released into the press and the press only retains the information that, ‘Oh, he’s accused.’”

Rivoire says he agreed to speak with APTN at the urging of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate [OMI], the international Catholic order he joined after becoming a priest at 28.

OMI looked after him in Nunavut for 30 years and since he returned to France, he says.

“Anything that belongs to us, even money, we don’t have anything. It’s all taken at our provincial home by the Oblates. It’s them who manage that.”

- Joannes Rivoire smiles as a young priest in Canada’s Arctic in this undated photo. Photo courtesy: Lieve Halsberghe

For example, Rivoire claims the Oblates recently took his Canadian passport.

“They told me, ‘You are Canadian. Give us your Canadian passport. We’re going to look at whether it’s up to date.'”

He says he applied for Canadian citizenship before leaving Nunavut. He doesn’t know why the Oblates want the document.

“I’m not going back anyway,” he says.

His room overlooking picturesque Lyon holds a single bed, a computer desk and a reading chair. There are no souvenirs to mark his lengthy career in the Arctic. Only a small crucifix that hangs on the wall.

And an unproven charge of being a sexual predator.

“Well, for me, I’ve never done anything that they are saying,” he says. “What more can I say?

“And I can’t prove it. It was so long ago, so long ago.”

- This crucifix is the only adornment in Rivoire’s third-floor room. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN News

Rivoire’s eyes light up.

He is pleased to discuss his missionary work.

“I went up to Chesterfield Inlet…that’s where I spent a few months to start learning the Eskimo language. Then they sent me to Igloolik.”

He lived in one-room buildings next to isolated trading posts.

The Fur Trade was in full swing.

“I found there was a people who were happy to live,” he says. “But they didn’t have, I didn’t know any Indians.

“And I believe that Indians, after being in contact with the whites, they lost a lot of things so there was animosity. Whereas the Eskimos were fully open, and they didn’t have anything to lose. They had everything to gain.”

READ MORE: Canada missed chance to have priest charged in France, says lawyer

Rivoire served as a church priest in the remote communities of Igloolik (1963-64), Naujaat (1965-75) and Arviat (1975-93).

He enjoyed meeting Inuit.

“Yes, I found them to be very easy going,” he says. “They would come, we would greet each other. We would give them a cup of coffee and sometimes we would also give them something to eat because they often didn’t have much to eat.”

Nunavut was still part of the Northwest Territories at the time.

Rivoire says missionary priests were mostly French or Belgian. “There were some Canadians,” he says, “but Canadians were not so interested in staying there.”

He says the government sent him annual medical kits to provide untrained aid.

“I’m not aware of having done anything seriously wrong,” he adds.

- Oblate priest Joannes Rivoire at his computer. Photo: Agustin Lucardi for APTN News

“I have touched penises…but this was as a nurse, a volunteer nurse. I was the only one…

“So when their penis was hurting then they would come see me. I even looked at girls,” he says.

“Back during those times, there was a syphilis epidemic. I was communicating with a doctor who was 100 kms south. I would tell him, ‘So here’s what I see, here’s what he’s complaining about. What can I do?’ He would advise me.

“I even did, and I’m pretty proud of it, I even delivered a baby.”

Rivoire says the Inuit he met were already baptized Catholic or Anglican [by Protestant priests in the territory].

Yet they believed in spirits.

He says he sowed a connection between their beliefs and the Catholic faith.

“Their animism was already geared towards that. From animism, they learned that it was a God. There weren’t spirits going all around, but there was a God who was here.”

- An exterior photo of the Oblate retirement home in Lyon, France. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN News

He was soon dressing in layers of clothing and fur against the cold.

“At that point, I was able to speak pretty good Eskimo,” he says. “I would leave and follow people to their camps. They were not permanent camps…everyone would go wherever they wanted. Things were always moving.”

Rivoire pauses.

“I spent 30 years – more than 30 years there – helping people however I could, and we don’t talk about anything else I did there, except [the allegations].”

“I don’t see what more I could do,” he adds. “If people don’t want to believe me, I can’t do anything.”

Rivoire is aware a delegation of Inuit leaders travelled to the Vatican last spring to discuss his case with Pope Francis. Shortly afterwards, he says he heard from the Oblates’ superior in Rome.

“He wrote to me saying, ‘There are allegations against me. What do you say about that?’ So I answered to him.”

Rivoire wouldn’t reveal what he said or share the letter with APTN.

- Joannes Rivoire laughs during an interview with APTN News. Photo: Agustin Lucardi for APTN News

Rivoire is also aware – “through the press” – that the Pope is scheduled to arrive in Canada on July 24 for a short tour to apologize for the church’s role in the notorious residential school system.

The Catholic church ran dozens of the schools designed by the federal government to assimilate Indigenous children into colonial culture from the 1880s through the 1990s.

Since then, thousands of former students have said they were emotionally, physically and sexually abused. They launched a series of class-action lawsuits seeking compensation for being stolen from their families and stripped of their original identities.

When asked if he is an abuser, Rivoire shakes his head. He never worked in the residential schools system, he added.

“No. We are accused but nobody is capable of telling me what the facts are: which person, what date, here’s what you did. No, it’s always allegations – just like that.”

Are the alleged victims lying?

“I’ve also heard that among Eskimos it’s frequent when they have a big problem to say it’s someone’s fault.”

- The Canadian centre of the missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) in Ottawa, Ont. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN News

Is he aware of clergy abusing children?

“Oh, I’ve heard of it, yes. Oh, we are just like anybody. We can let ourselves go sometimes. You know, it’s not because we are priests that we don’t have [laughs]…

Human needs?

“Yes. Priests are always set apart because they preach God. But we are humans like everyone else.”

Rivoire reviews photos of two of his accusers supplied by APTN. He says he doesn’t know them.

Perhaps they are after money, he suggests.

“I was told that in Canada, among Indians, there had been…some legal firms that specialize in court cases against whites for sexual abuses,” he says.

“So it will provide them with money and sometimes it would bring money to those who made the accusations. And years back, there was a very large case on the side of the Indians, and I think that the Eskimos thought, ‘We can do the same thing.’”

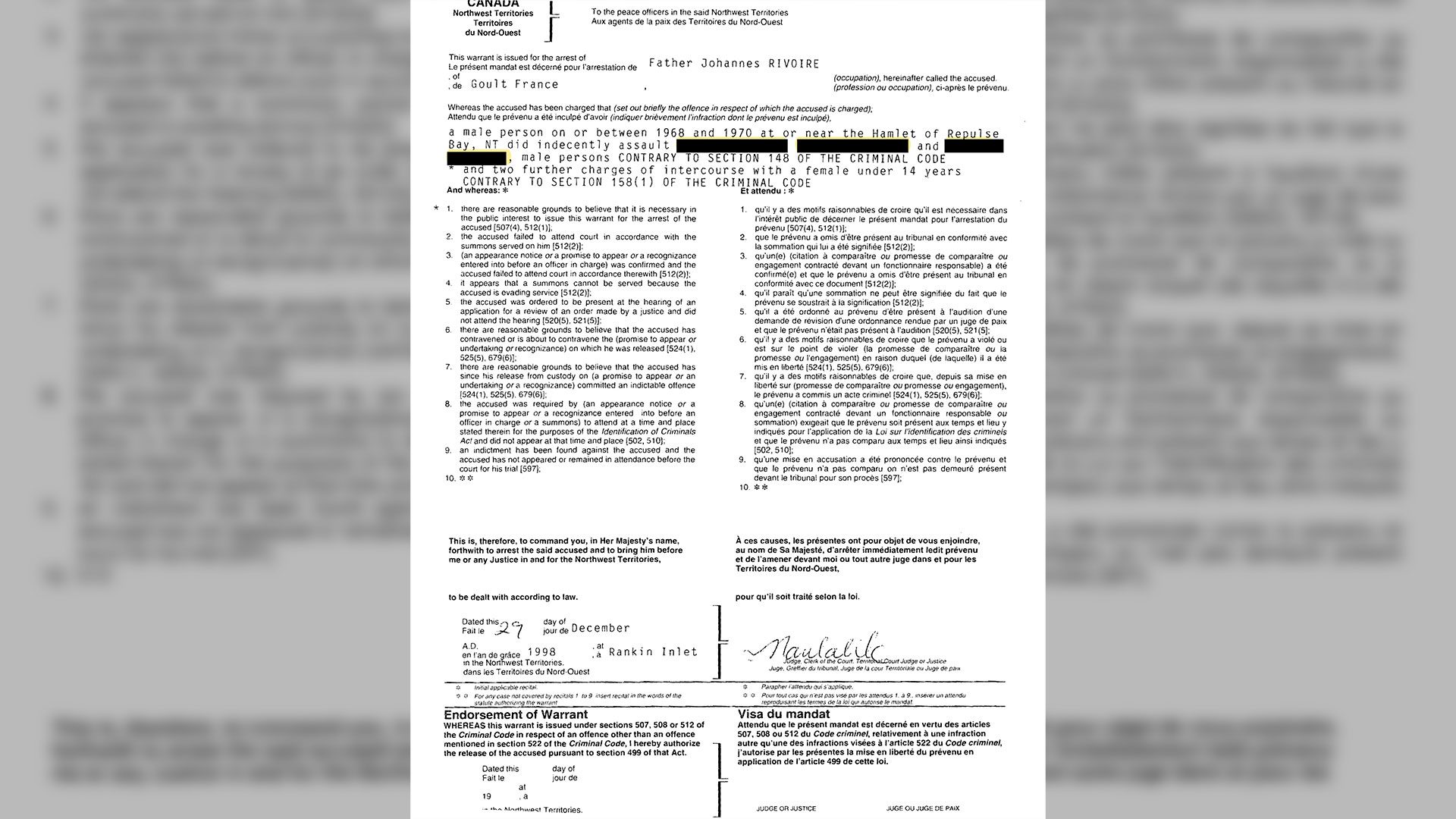

- The now-cancelled, first arrest warrant for Joannes Rivoire. APTN News

The RCMP in Nunavut first charged Rivoire in 1998 with five counts of child sexual abuse, but he had already left the country.

Four Inuit [one of whom died in 2012] accused him of sexually interfering with them between 1968 and 1970.

Rivoire never responded and Canada eventually abandoned the charges and vacated the Red Notice [Interpol warrant] in 2017.

A new charge – one count of indecent assault – was laid and a Canada-wide warrant issued in 2022 after an Inuk woman alleged Rivoire molested her on Sundays for five years, beginning in 1974.

“I remember what he [allegedly] used to do to me and tell me not to tell anyone,” she says after learning of “the monster’s” denial.

“He is lying to himself.”

The woman alleges the abuse began when she was six years old.

“He’s just making up stories,” she adds. “He doesn’t want to be blamed for what he (allegedly) did.”

- Joannes Rivoire is No. 17 in this blurry, archive photo of Oblate priests. Photo: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

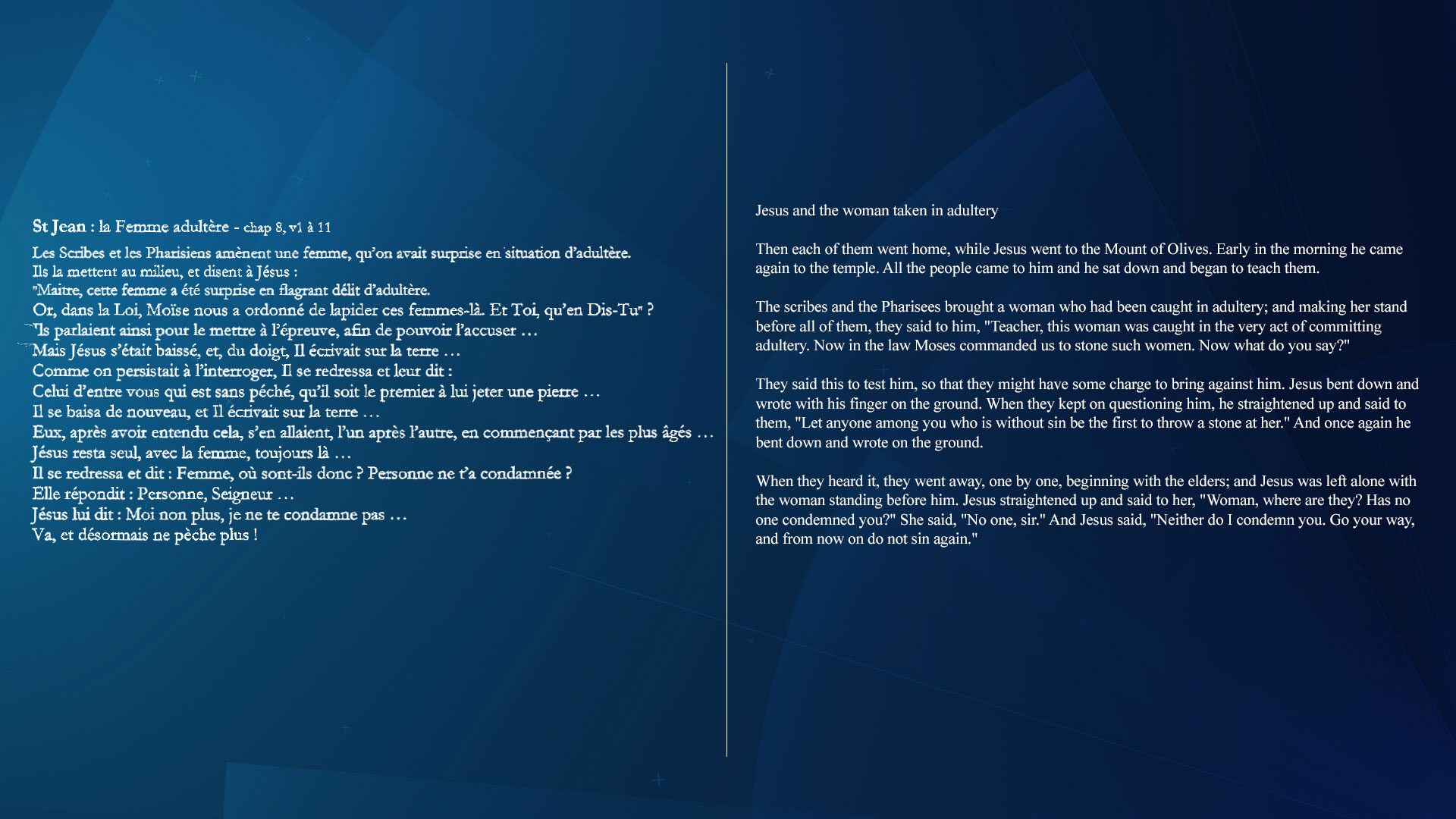

Rivoire retrieves a binder from a shelf underneath the computer.

“Do you know the gospels?” he asks while removing and handing over a type-written verse. “I really like this passage here. It dots the I’s, I think.”

The parable, in French, claims only those without fault can pass judgment on others.

“…It’s useful to me as people criticize me,” Rivoire explains. “I’m not perfect. I’m like you.”

Rivoire notes he has never heard from the RCMP in Nunavut. He says he learned of this latest historical charge “through the press.”

Why not reach out to RCMP in Nunavut to give his side of the story?

“No, never,” he says. “No. Why would I contact them?”

Rivoire leans back.

Despite the summer heat, he is wearing long pants, a long-sleeved shirt and an old fishing vest. His feet are sockless in oversized shoes.

He says he suffers from eczema all over his body and doesn’t “feel capable” of travelling to Canada to face his accusers in court.

Even if the Pope asked him to.

- Joannes Rivoire says this parable addresses the historical sexual abuse allegations against him. APTN

The tension between the Inuit and the Oblates is not his concern, it seems.

“This is a problem that does not remain in life,” he says, as he retrieves his cane at the end of the interview. “Me, I’m preparing myself to go to the other side.

“If we don’t see each other on this earth, we will see each other again.”

Watch Part 2 of Brittany Guyot’s story on Joannes Rivoire here: