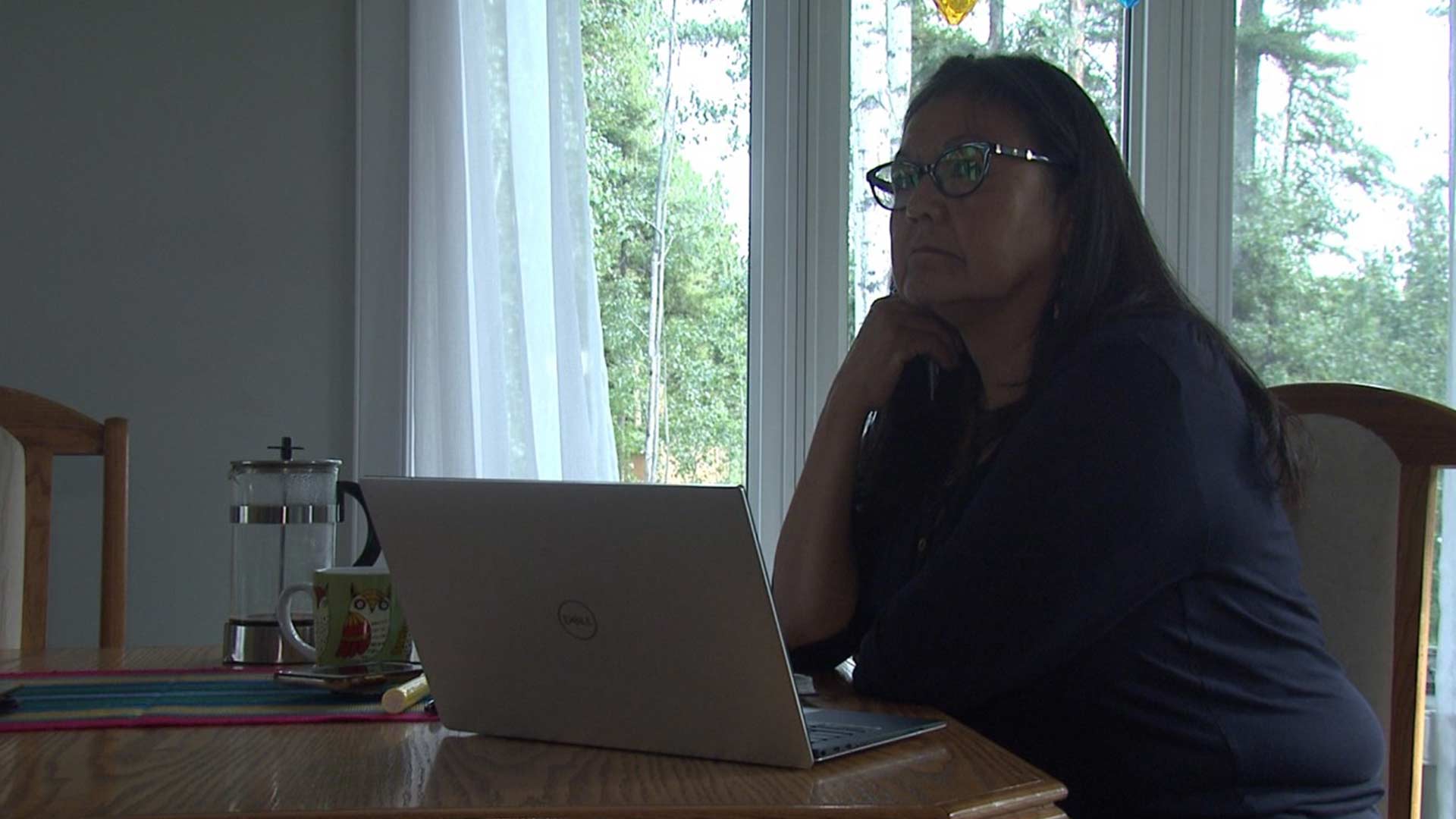

It was always a dream of Melanie Norwegian to live beside her mother and siblings where she grew up in Tthets’ek’ehdeli – Jean Marie River, Northwest Territories.

But it took nearly two decades for that dream to come true.

“I came back here in 1999. My dad made us two tent frames and we stayed there in the summer,” Norwegian said.

There are roughly 30 houses for the 80 people that make up the small community which is located in the Dehcho region, where the Jean Marie River meets the Mackenzie.

“My own daughter is in Fort Simpson, coming and going, she should be on her own but there’s no housing,” she said.

This year she landed a contract job with the territorial government she began to slowly fix up her house.

In January 2019, Norwegian, her husband and two kids moved into an old house owned by the First Nation band.

It had sat, mostly empty, for over a decade and required many repairs.

There was mould throughout, issues with the roof, broken pipes and no septic system.

But Norwegian was grateful.

“When I came to the band I took the opportunity for the house. “I applied to housing in the past and they denied me because me and my partner,” Norwegian said. Her partner had owned a house in Deline, NWT where he was from but had his other family members living there.

When she landed a contract job with the territorial government she began to slowly fix up her house.

But she was faced with another dilemma, when the band offered her the chance to rent two new mobile homes.

The two units had been given to the First Nation from the N.W.T. Housing Corporation.

But the houses sat on Crown land, where occupants would be required to pay for power poles, propane tanks and hook up to name a few expenses.

“I had to balance it out. I was thinking to myself, ‘how am I going to do this?’ I am just starting up a business. How will I do this if I have to pay land tax propane and power and other expenses to live,” she said.

Chief Stanley Sanguez admitted the two new mobile homes are a band aid solution for the ten community members who are currently in immediate need of housing and another ten on the waitlist.

He’s in discussion to start up an old sawmill which operated in the 1950s and 1960s until it burned down.

Over the last few decades, parts have been purchased for the mill. But the successful operation of a mill has never sustained.

“Here’s our first prototype log home we built with it. That was over a decade ago. The mill itself would harvest the wood and hopefully we would have log building training again trying to encourage people to help them build their own homes,” Sanguez said.

The chief said the band will need to ask the territorial government to back the project financially, but that discussion and action to these requests have been slow because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We want to start something here economic development with the sawmill. Not only for our community. Jean Marie had a history of building three sided log homes back when my dad was still alive. They use to give logs to Fort Simpson, Nahanni Butte, Fort Liard, Wrigley, the furthest one for three log side was Inuvik,” he said.

Norwegian’s aunt and former Jean Marie River chief Gladys Norwegian isn’t convinced a few new homes will have any long term impact, or get to the root of affordability and adequacy issues for First Nations Housing.

“We have been struggling with accommodations ever since we started living in communities. How is it that in 2020 we are still talking about it,” Norwegian said.

Now grand chief of Dehcho First Nation, Gladys Norwegian insists leaders need to remember they are talking about humanity and livelihoods when they speak about housing.

She’s looked into implementing transitional housing pilot programs used in First Nation communities in British Columbia.

“Community wide, think about some social problem. If people are willing to go to treatment for alcohol abuse, drug abuse than they would be considered priority as they leave to go do their treatment program. While they are away perhaps renovate their house or build a new home for them depending on the condition of their house,” she said.

But the grand chief believes collaborative approaches to resolving housing issues cannot solely fall on the shoulders of the territorial government or Dene Nation.

“In order for us to have a good, comfortable program of course we need to take it over. Of course, we need to run our own. Program that have been run by the government, by territorial government seem to not work for us and may work against us,” Norwegian said.

In the end Norwegian decided to stay put in her own old house, after she found out the history of her home.

She learned it had belonged to a respected elder who helped establish the community.

“If I ever were to leave this earth, I want to make sure my kids are stable and to give them an elder’s home more than a blessing,” Norwegian said.