Recent acquittals in the high-profile deaths of two young Indigenous people have some of their peers across Canada questioning whether reconciliation is possible.

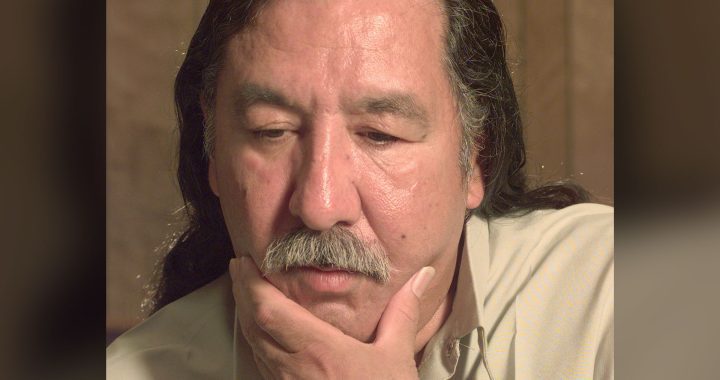

“I feel scared. I feel scared for urban Indigenous young people who are affected by too many systems that fail them,” said Michael Redhead Champagne, 30, an organizer with Aboriginal Youth Opportunities in Winnipeg.

“I am nervous for all of my relatives who are wrapped up in a justice system that doesn’t know what that word means.”

Last month, a jury found Raymond Cormier not guilty in the 2014 death of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine. Her body was found wrapped in a duvet cover and weighed down with rocks in Winnipeg’s Red River.

Less than two weeks earlier, a Saskatchewan jury found Gerald Stanley not guilty in the 2016 killing of 22-year-old Colten Boushie, who was shot after the vehicle he was in drove onto Stanley’s farm.

Both verdicts brought people into the streets to protest.

The Ontario First Nations Young Peoples Council said the verdicts highlight the “systemic racism that is pervading the Canadian justice system.” The Canadian Roots Exchange, a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth dedicated to reconciliation, posted a statement saying “racism, colonialism and white supremacy continue to thrive.”

Champagne said it’s hard to have faith in a justice system that ignores countless reports and recommendations, including the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry from 1991, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples from 1996 and calls to action by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

It’s time for action, he said.

“I want the justice system in Canada in general to quit asking Indigenous people what we need, because we have already told you,” he said. “Right now, we can’t have a conversation about reconciliation in this country until we feel that there is justice.”

Brendin Beaulieu, an 18-year-old Winnipeg high school student, is preparing for graduation. The six-foot-five teenager who likes to make music in his spare time said he has to deal with a “broken heart” as he grapples with “knowing there are things we can do but it’s going to take time.”

Vitriol online shows there’s a lot of talking about Indigenous youth but not nearly enough listening to them, Beaulieu said.

Jada Ross, 17, goes to a different high school across the city, but is having similar conversations with her friends and family. She said they are scared and saddened but determined to make change.

Lauren Chopek, 21, knows all too well how vulnerable Tina was on the city’s streets.

Chopek was sexually exploited as a teenager. Now, she runs the Midnight Medicine Walk to help others in the same position. She said it feels as if Indigenous people have been asking for justice for a long time, but it’s essential Canada hears it.

“I’ve been there in her shoes, and also misjudged and just ignored as a person on the street, being a child that needs to be somewhere safe. I needed help and I just got judged,” she said.

“Why are we always the ones standing up for ourselves? How come there is no one else vouching for us?”