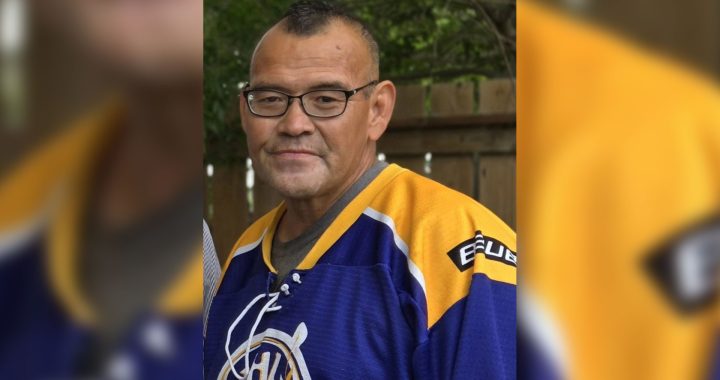

Harry LaForme says a miscarriage of justice commission is needed in Canada. Photo: Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP

Women and people of colour “urgently” need a commission to review claims of wrongful conviction, say two retired judges.

Harry LaForme, the first Indigenous lawyer on an appellate court in Canada, and Juanita Westmoreland-Traoré, the first Black judge in Quebec, were tasked with helping formulate a new Criminal Case Review Commission for Justice Canada.

They delivered their report and 51 recommendations to federal Justice Minister David Lametti on Dec. 9.

“The current system has failed to provide remedies for women, Indigenous or Black people in the same proportion as they are represented in Canada’s prisons,” said their executive summary.

“We believe that the new commission must be proactive and reach out to potential applicants, including Indigenous people, Black people, women and others who may have reasons to distrust a criminal justice system that had convicted them and denied their appeals.”

Justice advocates

The judges heard from justice advocates and exonerees during 45 virtual meetings earlier this year.

They say they were told it was crucial the new body – they suggested be called A Miscarriages of Justice Commission – be independent of government and work proactively to raise awareness of its mission.

“Our focus wants to be on what so far has not been in focus, which is people of colour who don’t even know that these kinds of reviews or examinations of their conviction even exist,” LaForme said in an interview Monday.

As of now, people must apply to the justice minister to consider wrongful convictions. In the past 20 years, only 20 of those applications have been sent back to the court for new trials or appeal hearings.

“There’s basically one a year. That’s totally unacceptable,” said LaForme, who is Anishinabe and a member of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation in southern Ontario.

“Out of those 20, one was Indigenous and one was Black – and they were men.”

Wrongful convictions

That number “does not reflect the population at risk for wrongful convictions as measured by the overrepresentation of Indigenous and Black people in Canada’s prisons,” the executive summary said.

“We believe that a new proactive and systemic approach is urgently needed.”

Justice Canada has said the number of Indigenous inmates in federal institutions rose to 28 per cent in 2017-2018 from 20 per cent of the total inmate population in 2008-2009, while Indigenous Peoples represent only 4.1 percent of the overall Canadian population.

Similarly, it said the percentage of federally incarcerated Indigenous women rose to 40 per cent from 32 per cent of the female inmate population.

LaForme said that’s why the new commission’s outreach efforts must include informing inmates about its existence and services.

“They’re going to go out and let people know – who are incarcerated and in prisons – let them know that there is this independent body out there that will be available to look at their allegations of wrongful conviction…and miscarriage of justice,” he said.

Lametti noted it was exonerees and justice advocates who have lobbied for such a commission to be created in Canada similar to ones that exist in other countries.

The report

“I am carefully reviewing the report and its recommendations,” Lametti said in a statement emailed to APTN News.

“Our Government is committed to establishing an independent commission. This report and the consultations Mr. LaForme and Ms. Westmoreland-Traoré conducted are an important step toward that goal.”

LaForme noted the new commission would not replace the work of university law schools and Innocence Canada that take on cases of wrongful convictions.

“There’s no reason why Innocence Canada couldn’t still be there,” he said.

“It’s not that we would be duplicating their work; it would be just another way to do some of the same stuff.”