Map shows the 21 health centres staffed by Indigenous Services Canada nurses on First Nations in Manitoba. Photo: Submitted

The union representing nurses who provide health care on First Nations agrees the system is in a code red.

“I applaud the chief at Cross Lake,” said Jennifer Carr, president of the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC). “I wish more chiefs would declare states of emergency when it comes to healthcare.”

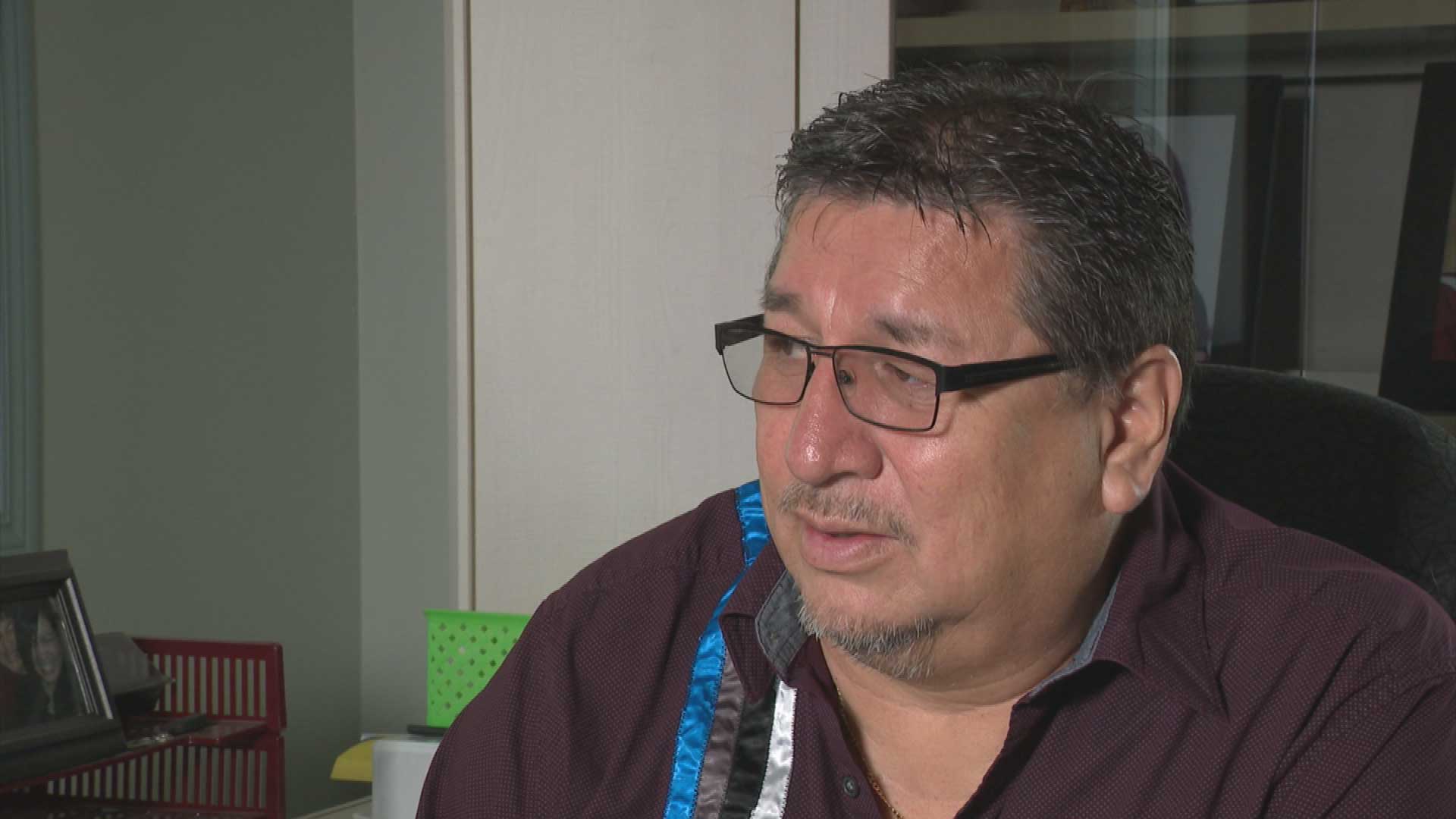

Cross Lake Cree Nation Chief David Monias said a shortage of nurses had put the community of 8,000 in a dire medical situation.

His band council declared a state of emergency on March 8 “with respect to health and medical care,” he told a virtual news conference last week from the community about 500 km north of Winnipeg.

Only four nurses were staffing the health centre (nursing station) forcing the band to limit services to emergencies only, added band councillor Donnie McKay.

“It’s not acceptable, it cannot be tolerated,” McKay told reporters. “We need to have the same standard of care as any other Canadian.”

Carr’s union represents 475 nurses who work for Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), among its 20,000 members comprised of scientists and professionals employed at the federal and some provincial and territorial levels of government.

“But that number (of ISC nurses) should be a lot higher given vacancy rates that exist,” Carr said in an interview with APTN News.

“I believe that they’re treating these communities like second-class citizens or third-world countries. It is to that point.”

The union said its nurses staff 70 health centres (or nursing stations) in Canada, with 21 in Manitoba and 21 in Ontario.

ISC confirmed to APTN there were “critical nursing shortages at the 21 nursing facilities run by ISC in remote Indigenous communities in Manitoba” or all of them.

Not properly staffed

But Carr said the health centres have not been properly staffed for years.

McKay agreed.

“We’ve never had enough (nurses); never had enough,” he said. “People are affected if they are being turned away.”

McKay said Cross Lake is supposed to have 13.5 nurses, which has dropped from the 24 it was first promised.

“Four nurses is not acceptable at all for 8,000 people,” McKay added. “I just spoke with a nurse yesterday. You can tell by the tone of her voice that they’re exhausted. We don’t blame the nurses.”

Carr said the federal government is supposed to provide primary medical care to First Nations people, instead of only the urgent care Cross Lake is receiving now.

“For me, it’s not just about my members,” Carr noted. “I listen to the federal government talk about the provinces should be doing this [for First Nations] and sending them money, and I’m saying, ‘But wait, you have communities that are also suffering and you haven’t invested in and you hold the purse strings.’

“Then also the reconciliation [with Indigenous peoples] talk,” she added.

“How can you say you’re meeting reconciliation or you take this seriously when you’re not looking at the basic services that you are providing?”

Helga Hamilton, health director for Cross Lake, said the problem didn’t develop overnight.

“What we’re talking about here – the shortage of nurses – is ongoing. It’s not something that just happened. But it’s perpetuated to the point that it is critical,” she said.

Nursing is critical

“We’re at a point right now where nursing is critical; we need to find nurses where we can, as quickly as we can.”

“Working at four nurses, five nurses for a 24-hour period, seven days a week is extremely dangerous, and it needs to be addressed.”

Nearby Manto Sipi First Nation is in the same boat, said Chief Michael Yellowback.

“We had a press conference in Ottawa in April 2023 addressing the same thing,” he told reporters. “The nursing shortages are compromising the health and safety of our community members.

“We’re being treated like third-class citizens in our own country.”

Supplemented by doctors

The nursing care on reserve is supplemented by doctors flying into communities on a rotation and consulting over the phone from city hospitals.

Carr said the nursing shortage may be acute now but has taken years to fester.

She said it has been exacerbated by competition from private nursing agencies who hire public nurses for better pay and improved conditions, then turn around and charge government high fees to fill ISC vacancies they helped create.

And the ISC roles remain unfilled, Carr said.

Choose where they go

“Those nurses get to choose where they go. They have individual contracts. They’re not committed to the community,” she noted.

“They’re also getting paid astronomically higher rates than the nurses that we have. They also get bonuses for working Christmas (day) and Nursing Week.”

Carr said it has created a “tumultuous situation” between nurses who work for ISC and “are really committed to communities” and ones that “fly in and fly out” with better pay and their choice of communities.

Devoted to their jobs

But despite the lack of respect and higher wages from the government, Carr said ISC nurses are devoted to their jobs.

“The nurses who still remain at the stations … they have an immense pride in the communities that they are serving,” she said. “They feel connections to them and they’ve built relationships, and that’s important.

“When you bring in a travel nurse or somebody who’s not familiar with the community you would have poor health outcomes as well.”