The federal minister for addictions and mental health says it’s too early to draw conclusions about drug decriminalization after British Columbia asked Ottawa to scale back its pilot to help curb concerns over public drug use.

Ya’ara Saks noted Monday that the province is only a year into its three-year pilot project, which began in early 2023.

To make it happen, Health Canada issued an exemption to federal drug laws decriminalizing possession of small amounts of certain illegal drugs, including heroin, fentanyl, cocaine and methamphetamine.

“We’re still evaluating the data,” the minister said.

But on Friday, B.C. Premier David Eby asked Health Canada to amend that exemption order to recriminalize the use of those drugs in public spaces such as hospitals and restaurants.

While adults would still be allowed to use such drugs in private, they could be arrested for using them in public.

“Illicit drugs and hard drugs should not be used where kids are playing where patients are recovering where a community life is lived,” said Eby.

In January 2023, a three year pilot project to decriminalize 2.5 grams of hard drugs started in B.C. Just over a year later, some say it’s not working.

“Since day one, the British Columbia Association of Chiefs of Police has expressed significant concern with the issue of public consumption of illicit drugs,” said Fiona Wilson, deputy chief, Vancouver police.

“This concern is based on a fundamental belief in the importance of funding a balance between ensuring that people who use drugs are not unnecessarily criminalized while all members in communities across this province feel safe.”

Now B.C. wants to amend the decriminalization project to give police, “the tools they need to enforce the law anytime someone is using drugs in an inappropriate location compromising public safety,” said Eby.

The request followed months of backlash from residents, healthcare workers, police and conservative politicians about the project’s effect on public safety.

Saks said she met with her provincial counterpart on Friday and the province’s amendment request is under review.

“The overdose crisis, as I’ve said before and I say again, is a health crisis issue. It is not a criminal one,” Saks told reporters.

B.C. was the first jurisdiction in Canada to seek the decriminalization of small amounts of hard drugs.

The province declared drug-related overdose deaths to be a public health emergency in 2016, and the crisis worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eby told reporters Monday that other jurisdictions can learn from its experience with decriminalization to date.

He said there must be resources in place to address public drug use.

“There are important lessons to be learned on where we are to date, that don’t need to be repeated,” he said.

“Addressing the public’s concern around public use is critical to having their understanding about taking a health approach to addiction. Balancing those two things is core, and I hope other jurisdictions take that lesson and don’t repeat our mistakes.”

Request in Ontario

Toronto has also requested an exemption from Health Canada.

Toronto Public Health said in a statement that it is monitoring B.C’s experience. It added that in its proposed model, public drug use would remain illegal.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford repeated his call Monday for Toronto to drop that application.

Ford said he’s spoken to Eby about how things have gone in B.C., and said “It’s turned into a nightmare.”

Saks said Toronto’s request is also under review, and each request for decriminalization will be treated individually.

“We work with jurisdictions on a case-by-case basis, making sure we have a full suite of tools available to help vulnerable populations. That includes prevention, that includes harm reduction, that includes treatment and it includes a full set of health considerations,” she said.

“It’s not an apples-to-apples situation and we continue to partner and work with jurisdictions.”

More than 40,000 people have died from opioid-related deaths countrywide since 2016, when the Public Health Agency of Canada began collecting such data.

The agency says 22 people die every day from toxic drug deaths, and fentanyl is the leading cause. Most of the deaths are in B.C., Ontario and Alberta.

Health officials and advocates for drug users warn the situation is only worsening, given an increasingly toxic supply of drugs.

During question period on Monday, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pressed the Liberal government on B.C.’s about-face.

And he is requesting an emergency debate on the issue in the House of Commons.

“Until Justin Trudeau’s dangerous drug decriminalization policy is entirely dismantled, it will continue to cause death, chaos and carnage across Canada,” he said in a letter to House of Commons Speaker Greg Fergus.

Poilievre has repeatedly called public drug use in cities like Vancouver a “dangerous experiment.”

He charges that it fuels addiction, and pledges that a future Conservative government would pull out from harm reduction strategies and focus on recovery-oriented approaches instead.

Advocacy groups such as Moms Stop the Harm have asked to meet with Poilievre out of concern his proposal is ignoring evidence that harm-reduction strategies work to save lives.

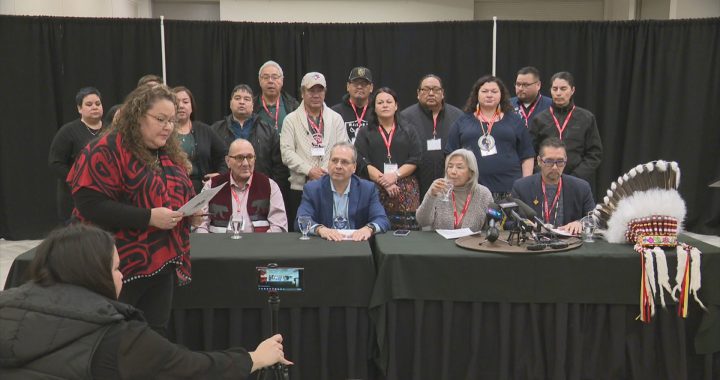

Its co-founder spoke Monday at a parliamentary committee that has been studying the opioid epidemic.

In a statement before her appearance, Petra Schulz said it has been “upsetting and infuriating” to see loved ones’ deaths politicized with “misinformation and outright lies.”

“I urge members of Parliament to stop the angry, harmful and polarizing rhetoric and social-media posts, and to listen to people who use drugs when developing drug policy.”

With files from the Canadian Press