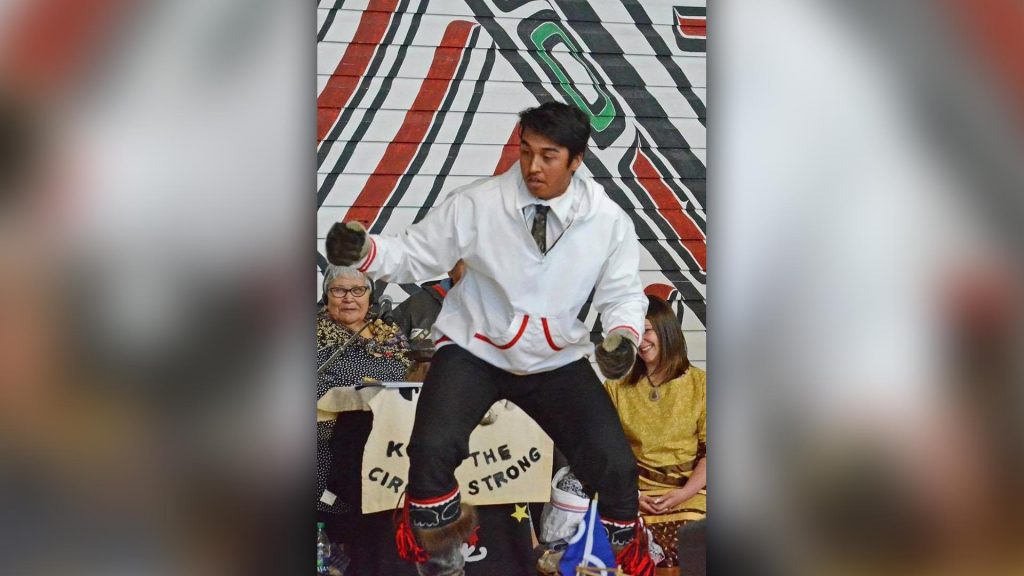

Joe David “J.D.” Nasogaluak performing at the ceremony for the release of the report from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

A drum and dance troupe from Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., takes the stage across the river from the nation’s capital.

Five young men drum and three women dance. They finish and the three young men take their turn. They dance, move their arms at their sides as if paddling. The acoustics echo through the building. The tempo quickens, the movements are sharp, powerful, symbolic, poetic. The prime minister looks on.

It’s June 3, 2019. The presentation ceremony of the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls draws to close. Symbols of Indigenous cultural survival ornament the walls at a ceremony that uses the word genocide to describe Indigenous peoples’ relationship with the Canadian state.

The young Inuvialuit man dancing in the middle is 17-year-old Joe David “J.D.” Nasogaluak.

He’s the lead plaintiff in an uncertified $600-million class action against northern RCMP.

It was launched in 2018 on behalf of all First Nations, Inuit and Metis in Nunavut, N.W.T., and the Yukon who were harmed by unnecessary use of force by RCMP from 1928 until now.

As she discusses the photo she took that day, his mother Diane says she had to convince J.D. to attend the closing ceremony and meet Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Two Tuktoyaktuk RCMP constables arrested J.D. in 2017 when he was 15. He claims they assaulted, tasered, choked and hurled racial slurs at him.

Recent events have thrust J.D.’s experience and many others like it into the spotlight as people call for systemic change to policing in Canada.

Diane, also J.D.’s litigation guardian, tells APTN News the 2017 incident left the family struggling with a lot of anger.

“It was really hard the first year. The first year we had to keep an eye on him. My girl, all my kids were hurt because of that,” she says. “He was suicidal, he wanted to kill himself, like he felt so awful.”

She says her young children now fear the police

“He never did nothing wrong. They were just driving around being kids and I had to really talk to him and let him know that, you know – they’re racist,” says Diane.

She’s not the only one calling the RCMP racist. On Wednesday, former Green Party leader Elizabeth May call the RCMP “a racist institution.”

Diane and J.D.’s father Joe Sr. say a Minneapolis police officer’s alleged murder of an unarmed Black man named George Floyd reminds them of what happened to their son.

Every day federal politicians face calls to reform policing and end systemic discrimination in the ranks.

Joe Sr. compares the situation now to the ice break-up on a river during spring thaw.

“Something has to change. Right now, it’s like in the river, the ice jammed, the water’s coming. You can’t do nothing but just wait and accept what’s happening in front of you. Sooner or later, something’s going to happen,” he says.

Joe Sr. pauses as he searches for the right words. He feels people are fed up.

“We’re just accepting, I’m talking on behalf of the Native, the people up here in the North. We just accept what is happening to us for so long that people are tired of it. I’m tired of it.”

His voice joins a chorus calling for systemic change to policing.

“Everybody needs somebody to start – like J.D., J.D.’s case. We need to change it with this case.”

Diane agrees.

“We know it’s wrong what they’re doing, hurting people and young kids like my son. He was only 15-years-old,” she says. “There’s other people out there going through the same thing who are Aboriginal. We all got to stay together and fight this thing so things can change and get better for us.”

The RCMP dispute J.D.’s account of the arrest in a court affidavit obtained by APTN News. Const. Joshua Savill says he did not use unlawful force or taser the young man. No allegations have been tested in court.

Lawyers emphasize that the case is about institutional wrongs, systemic discrimination and widespread neglect rather than the details of any individual case.

J.D.’s experience represents what the suit alleges is a regular occurrence in all three territories where the RCMP have sole jurisdiction over law enforcement with little civilian oversight.

“One of the goals of class actions is behaviour modification – to force bad actors to change their ways so that they no longer conduct themselves in ways that cause harm and by consequence, costly damages claims,” says Andrew Eckart, staff lawyer at Windsor University’s Class Action Clinic.

“If the courts agree that the RCMP conducted itself unlawfully, the class action will not only provide an avenue for class members to be appropriately compensated, but it could also lead to more progressive institutional changes leading (hopefully) to a reduction of harmful systemic racism,” he explains in an email to APTN.

But it’s impossible to predict how long a class action like this could take, he adds. It might take years but it also could settle at any point. That’s up to Canada. Lawyers hope to argue for certification in October.

“If the case is certified and then goes to trial, there will likely be a lengthy discovery process in which the parties will exchange all relevant documents and ask questions of the plaintiffs and representatives from the RCMP. The discovery process alone may take years,” he says.

“If it goes to trial, then the trial would last several months likely and a trial decision might not be rendered for many months more. Of course, the case could settle at any time during any of these processes.”

Joe Sr. is fine with that. It’s about changing the system for people in the future.

“It’s better to take years than not happen,” he says. “If it could help one person, it’ll work. It means something. It’s all about that one person that could be affected.”