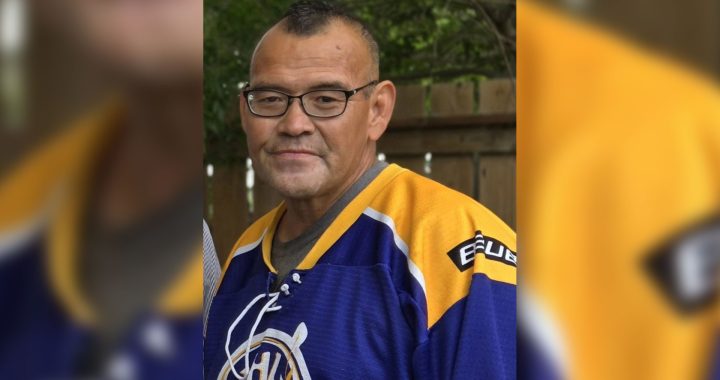

Steve Smith still beams with pride when it comes to his late father, Elijah Smith.

Elijah is best known for his ground breaking work in leading land claim and self-government agreements for First Nations in Yukon.

While his service in the Second World War hasn’t received as much attention as his work later on in life, his son says it was a momentous accomplishment for the First Nations’ leader.

“He was really proud of having a uniform and serving the country and going off (to fight),” Smith says.

Elijah, also known as Tä Me in Southern Tutchone, was born in the community of Champagne in 1912.

In 1939, at age 27, Elijah enfranchised himself in order to enlist in the war. As a result, he lost his legal identity as a First Nations person in the eyes of the government to become a full Canadian citizen.

“My dad did not fight in the Second World War for any glorification or gratification through a war journey or recognition,” Smith says. “He saw it as an opportunity to see the world to do his part, and I think most veterans did that.”

Elijah served in the Royal Canadian Regiment, an infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. He was stationed overseas in England for much of his service and was trained in heavy equipment operation.

He survived the failed Dieppe Raid of Aug. 19, 1942 where mainly Canadian troops attacked the German-occupied port in northern France.

Hundreds died or were taken prisoner.

Smith says his father also witnessed the carnage of D-Day in Normandy, France, in 1944, though he’s unsure when Elijah landed there or if he saw action.

He notes Elijah was reluctant to talk about what he witnessed.

“I think this is typical of a Canadian soldier or someone who fought in the Second Wold War,” Smith says.

However, Elijah did talk about his positive experiences fighting alongside non-Indigenous soldiers.

“Fighting side by side with other individuals who are not of the same race fashioned his outlook when he came home,” Smith says.

“The war taught him a German didn’t decipher between a First Nation person, a French person, an Italian person or a British person. If you had the wrong uniform, they still shot at you.”

Treated as an unequal

Smith says despite Elijah being treated as an equal during the War, that was not the case when he returned home.

Elijah was disenfranchised when he returned back to Yukon as he had given up his Indian status.

Smith says his father was further dismayed to learn he didn’t qualify for the same benefits as non-Indigenous veterans, such as receiving a parcel of land for farming, because he wasn’t considered a full Canadian citizen by the federal government.

“He was like ‘OK, well this is interesting that I’m not really a citizen within my own homeland,’” Smith says.

While Smith doesn’t think the War directly inspired Elijah’s leadership roles later on, he feels it did lay “a really big foundation.”

Despite not having aspirations to become a leader, Elijah was later nominated and elected chief of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) in the late 1960s. Smith says at the time it was common for First Nations membership to nominate people for chief and council without their knowledge.

While his father was initially angry to learn he had been elected, Smith says he was a natural leader who was committed to ensuring First Nations people in Yukon weren’t treated as second-class citizens.

Elijah went on to become chief of the Whitehorse Indian Band, now known as the Kwanlin Dün First Nation.

He was also heavily involved in forming the Yukon Native Brotherhood, the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians and what is now the Council of Yukon First Nations.

In 1973, he spearheaded a delegation of First Nations leaders from Yukon to Ottawa to meet with former prime minister Pierre Trudeau. It was there he presented Trudeau with Together Today for our Children Tomorrow, a policy paper that paved the way for the territory’s modern land claim negotiations.

Almost 50 years later, Yukon is leading Canada in settled land claims as 11 of the 14 First Nations in the territory have reached final agreements and are no longer governed by the Indian Act.

Smith says his father was a negotiator at heart and disdained fighting which he witnessed during the War.

“I believe his leadership style came directly from what he experienced in the War, where he saw directly what the consequences of not negotiating, not talking, not settling grievances, (can lead to),” Smith says.

“One of the things the war did teach him is that fighting is the absolute last resort.”

Smith, who recently opted not to run in the last CAFN election after eight years as chief, says his father is an inspiration.

“I have a responsibility to his sacrifice to ensure that I try to live up to his ideals,” he says.

Elijah remained a respected leader in Yukon until his death in 1991.

Smith says it’s important to remember all soldiers like his father who put their life on the line.

“I’m proud of the fact that he fought in the Second World War. He served his country, and he served all of us today.”