A bust of Duke Kahanamoku is one of the items on display at the surfing museum in Huntington Beach, Cal. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN News

When Olympic surfers ‘Hang Ten’ as part of the 2024 Summer Games in Paris, they’ll have an Indigenous athlete to thank.

Duke Kahanamoku was an Olympic swimmer, Hollywood actor and Honolulu sheriff.

But his greatest accomplishment may have been introducing surfing to southern California and Australia, says Peter (PT) Townend, executive director of the Huntington Beach International Surf Museum in southern California.

“He was the Sultan of Surf.”

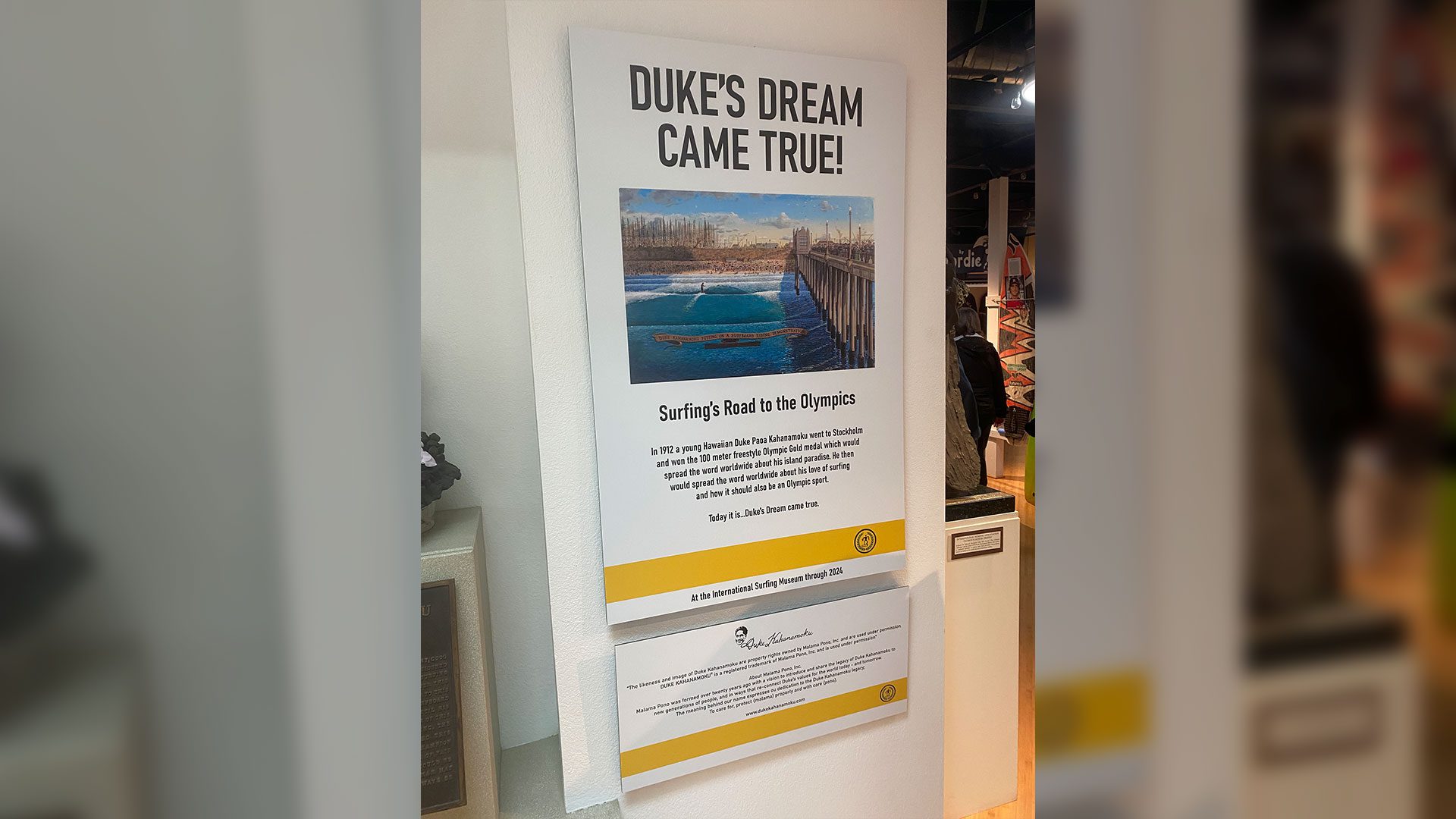

An exhibit that chronicles Kahanamoku’s life and his push to see surfing recognized as an Olympic sport is now on at the museum in what is also known as Surf City USA.

“It took 100 years for that to happen and now we have Olympians – surfing, gold-medal Olympians,” adds Townend, the world’s first professional surfing champion and chief curator of the exhibit.

Sadly, Kahanamoku died in 1968, decades before surfing would make its Olympic debut at the 2020 Games in Tokyo.

But the achievement remains his legacy, says Townend, an Australian living in Huntington Beach, less than an hour south of Los Angeles.

“By the time I got to Hawaii – he had died in 1968 – I got to Hawaii in ‘72. But I was able to surf in the tournament – the Duke Kahanamoku Tournament on ABC Wide World of Sports.”

Townend spent six months researching Kahanamoku’s life to build an exhibit comprised of early surfboards, symbols of California beach culture and media accounts of Kahanamoku demonstrating the sport on both coasts.

In one of the most dramatic photos, Kahanamoku is shown standing alone on a surfboard facing an Atlantic City, N.J., beach crowded with onlookers.

“Most people don’t even know he surfed in Atlantic City before he surfed in California,” recounts Townend, his voice full of admiration. “It was front page news in the (Atlantic City Evening Union) newspaper.”

Kahanamoku was born in 1890 before Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state and grew up to become a champion swimmer. He won five Olympic medals for his kingdom in 1912, 1920 and 1924.

It was after he and another athlete of colour – Native American Jim Thorpe – medalled at the Games in Sweden that Kahanamoku showcased the sport of surfing in Atlantic City.

“Surfing goes back a long time,” Kahanamoku told Surfer Magazine in 1967, “but I remember when I was about eight years old, I guess, when I started surfing here at Waikiki Beach (in Honolulu). That was a long time ago.

“We had nobody to teach us how to ride waves or swim. As a matter of fact, we had to learn by ourselves – especially the surfboarding.”

Some of the early surfboards on display at the museum resemble heavy toboggans: thick planks of wood with curled ends. Townend said it would be many generations before lighter and shapelier boards were made of fibreglass with foam cores.

It didn’t take long for Hollywood to notice Kahanamoku’s prowess in and on the water and cast him in bit parts in movies.

He was beloved in his native Hawaii where he was voted sheriff of Honolulu a record 13 times and named “Ambassador of Aloha”.

The exhibit Duke’s Dream Came True: Surfing’s Road to the Olympics is not the only nod to Kahanamoku in Huntington Beach, an oceanfront community.

There is a statue of Duke, a star on a Walk of Fame, and bright banners on lampposts proclaiming: “Duke’s Dream Came True”.

The restaurant that bears his name sits at the foot of the famous Huntington Beach pier with tables that overlook the Pacific and waiters dressed in Hawaiian shirts.

Townend said the exhibit was timed to coincide with this Olympic year.

“What’s amazing to me (is that) no one’s really told the Duke story from the point of (an exhibit in) a museum,” he tells APTN News. “And that was the great challenge: to find all that stuff about his life.

“The back story of all of that … the fact that he was a Black Hawaiian … he faced the same challenges racially in that period of time when he was an Olympian.”

Townend said a documentary about Duke called Waterman came out in 2021

While the exhibit focuses on Kahanamoku’s success, Townend is well aware of anti-Indigenous racism having grown up in Australia and now living in America.

“I think we, the white people, treated them very badly,” Townend says. “That’s my opinion. And it’s good to see some stuff happening to try to redo whatever the damage that was done.”

Having spawned a sport that developed a cult following and continues to grow in popularity, it was only fitting that Kahanamoku be buried at sea.

The funeral was the biggest Hawaii had ever seen, according the book Duke Kahanamoku and the Spread of Surfing, and his ashes were scattered into the ocean.