Willow Fiddler

APTN National News

On a cold night in Feburary 2013, Lena Anderson tied the drawstring from her pants to a bar in the back of a police truck and hanged herself.

Anderson was 23, and a mother.

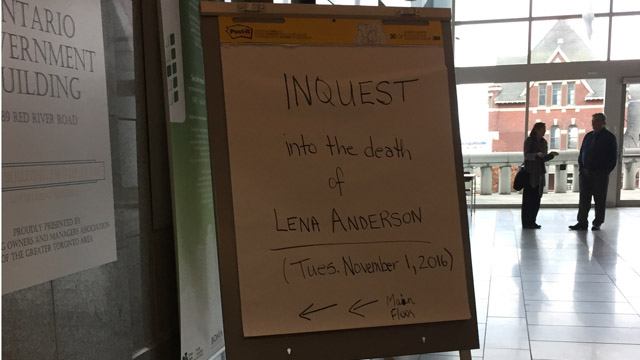

An inquest into the circumstances of her death wrapped up in Thunder Bay, Ont., with 28 recommendations to prevent her tragic death from happening again.

A jury of five heard five days of testimony from 12 witnesses, including how Anderson was handcuffed and detained in the back of a Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service (NAPS) truck on Feb. 1, 2013.

The police officer on-duty in the First Nations community Kasabonika left Anderson alone in the truck for 16 minutes.

Anderson had been struggling with the recent suicides of two loved ones when she died.

The Inquest recommendations address primarily issues related to First Nations policing and the state of mental health on-reserve.

As the presiding coroner read the jury’s verdict aloud, Anderson’s mother Maryanne Shewaybick sat with her head down and arms crossed. Beside her, Anderson’s 7-year old daughter Perseus.

“I’m pissed off,” Shewaybick said during the inquest. It was difficult for her to sit and hear the details of her daughter’s preventable death.

Anderson had been drinking at a house party when community members alerted local authorities to their concerns that her then three year old child was also at the party.

The NAPS officer and a local child welfare worker investigated.

When she learned that her daughter was being removed from the home, Anderson’s behaviour became erratic, hysterical the jury heard.

According to police, Anderson was not facing any charges when she was placed in handcuffs. Instead, she was being held until the alcohol wore off. Anderson’s daughter was being taken to a family member until she sobered up. Lena Anderson would be dead before any of that happened.

Anderson had a history of suicide attempts. The arresting officer had no knowledge of this, prompting a discussion about whether it would have impacted his decision to leave Anderson unattended. It was pointed out that access to this information could have allowed the police and social workers to ensure Anderson wasn’t a risk to herself.

“We speak for the dead to protect the living,” Ontario Coroner

Jury recommendations are, in theory, a tool for protecting the living. The problem many see is, the recommendations aren`t binding.

The jury isn’t even obligated to deliver any recommendations with its verdict.

It’s frustrating, said Mike Metatawabin, chair of the NAPS Board.

“They need to be enforced,” Metatawabin said.

The 28 recommendations include:

- To ensure adequate and sustainable funding to provide appropriate detachment buildings in each community.

- To ensure adequate and sustainable funding to provide appropriate maintenance and upkeep.

- Ensure that all police officers review the policies on prisoner care and identification of individuals at risk of self-harm

- Ensure that prisoners are not held in police vehicles for any longer than is necessary to transport them to proper holding cells.

See full list of recommendations here: Lena Anderson

These recommendations have not been signed off by Ontario’s Chief Coroner.

And they have been heard before.

In 2009, a jury returned with similar recommendations in the Kashechewan Inquest.

Ricardo Wesley and James Goodwin were locked up at the Kashechewan police detachment on a cold night in January 2006. One of men lit their mattress on fire. The NAPS detachment was a broken down building with no heat, and no smoke detectors.

The substandard building burned to the ground with them inside.

The jury found that the deaths of the two young men could have been prevented if First Nations communities in Nishnawbe-Aski Nation received equitable funding for policing from Ontario and Canada.

Lawyer Julian Falconer represented the family of Ricardo Wesley at the Inquest and NAPS at the Anderson Inquest. He refers to the detachments in both cases “death traps”.

He said reports and recommendations calling on both levels of government to take action has fallen on deaf ears time and time again.

“First Nations are ignored, Indigenous people in this country are ignored,” he said.

Metatawabin told the jury NAPS has faced chronic challenges on a continual basis since 1998 and that it’s been well-documented.

Immediately after Anderson’s death, Nishnawbe-Aski Nation and NAPS issued a notice, declaring they could no longer ensure the safety of their communities.

“The sad part of that is other than the chief coroner no representative of either Ontario or Canada responded to the public safety notice and that’s par for the course,” said Falconer.

The condition of the Kasabonika Lake detachment was no secret.

In fact, five years before Anderson’s death, the chief of police ordered that there “be no incarcerations in this facility, period” after an officer expressed concerns over the conditions of the detachment.

In 2008 an officer described it this way.

“The cell doors are made up of small metal bars and wire meshing. The cells have no lights, no toilets. We have to take prisoner out of the cells and down the hall in the band office to the washrooms, the floors are riped (sic) up and both have holes in the floors which for some, are used as the washroom.”

Years later saw no improvements in Kasabonika.

In fact, conditions got worse. It was winter in 2013 and the furnace wasn’t working. Officers were forced to lodge prisoners in their running police trucks to keep them warm.

A new detachment was on its way to Kasabonika at the time of Anderson’s death, but pieces of the modular unit were stuck on the winter road, according to Cst. Troy Woldarek, a NAPS officer who was off duty at the time.

Despite the deplorable conditions, Woldarek told the jury he felt lucky to be in Kasabonika. It was his first posting after completing provincial police training seven years ago.

His first partner was from the community which Woldarek said made him feel “lucky”.

He came to rely on community members especially when he was alone and the only officer in the community.

Officer shortage is another example of chronic challenges familiar to the troubled NAPS. Reports show that at any given time 18 per cent of officers are off due to sickness, injury or stress. Not enough officers means working alone and for long periods of time.

“My personal record is 42 hours,” Woldarek told the jury was the longest stretch he’s pulled. The closest backup at any given time would be an hour and a half plane ride away in Sioux Lookout.

On the day of Anderson’s death, Woldarek said he had been up for 24 hours – a sudden baby death occurred on his shift the night before.

He had been sleeping for just a couple of hours when his partner, who was working day shift, woke him to come in early. He was told that someone in the truck was being held and needed to be watched while he investigated further.

Years of working alone and facing the deadly risks that come with it, frustrated NAPS officers who voted almost unanimously in favor of strike action this past summer. They had the full support of the communities they serve.

The stark contrast of the working conditions between NAPS and its provincial counterpart the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) was highlighted in a 2007 documentary called A Sacred Calling. Footage shows a NAPS detachment in Wunnumin Lake that had no working bathroom.

A slop pail was used for prisoners and officers had to empty them as part of their duties.

NAPS police chief Terry Armstrong told the jury that while there have been new detachments in some communities, there are still a number that don’t meet standards.

The jury was presented evidence that 30 detachments were inspected last year and more than $1 million would be needed to meet fire code standards.

NAPS says they need an additional $16 million to its current budget of $27 million and $7 million in capital funding for two new detachments.

Metatawabin said the province agreed to move forward with legislating NAPS under the province’s Police Services Act last summer.

They were supposed to make an announcement in September but he is still waiting for that happen.

In a bid to put pressure on the province, NAPS asked the jury to give Ontario an ultimatum of starting the legislative process by March 31, 2017 or simply get rid of NAPS altogether.

The jury did not include the recommendation in their final verdict.

A new labor agreement was ratified by NAPS officers in September, avoiding any strike action. An increase of 30 officers and improved communications will provide some relief. But it’s just a drop in the bucket.

At the end of the inquest, Christa Big Canoe, the lawyer representing the Anderson family, told the jury it is Shewaybick’s hope that she can now move forward.

Big Canoe told the jury in her closing comments that the issues and concerns they’ve heard are the result of Canadian law and policy.

“These aren’t unreasonable expectations,” she said of the recommendations the jury was asked to consider.

“I have mixed feelings,” Shewaybick said before the jury came back with the verdict.