APTN Investigates: Decolonizing Museums – Watch Part 1 here.

The Royal British Columbia Museum’s decolonization journey took a personal turn in the summer of 2020.

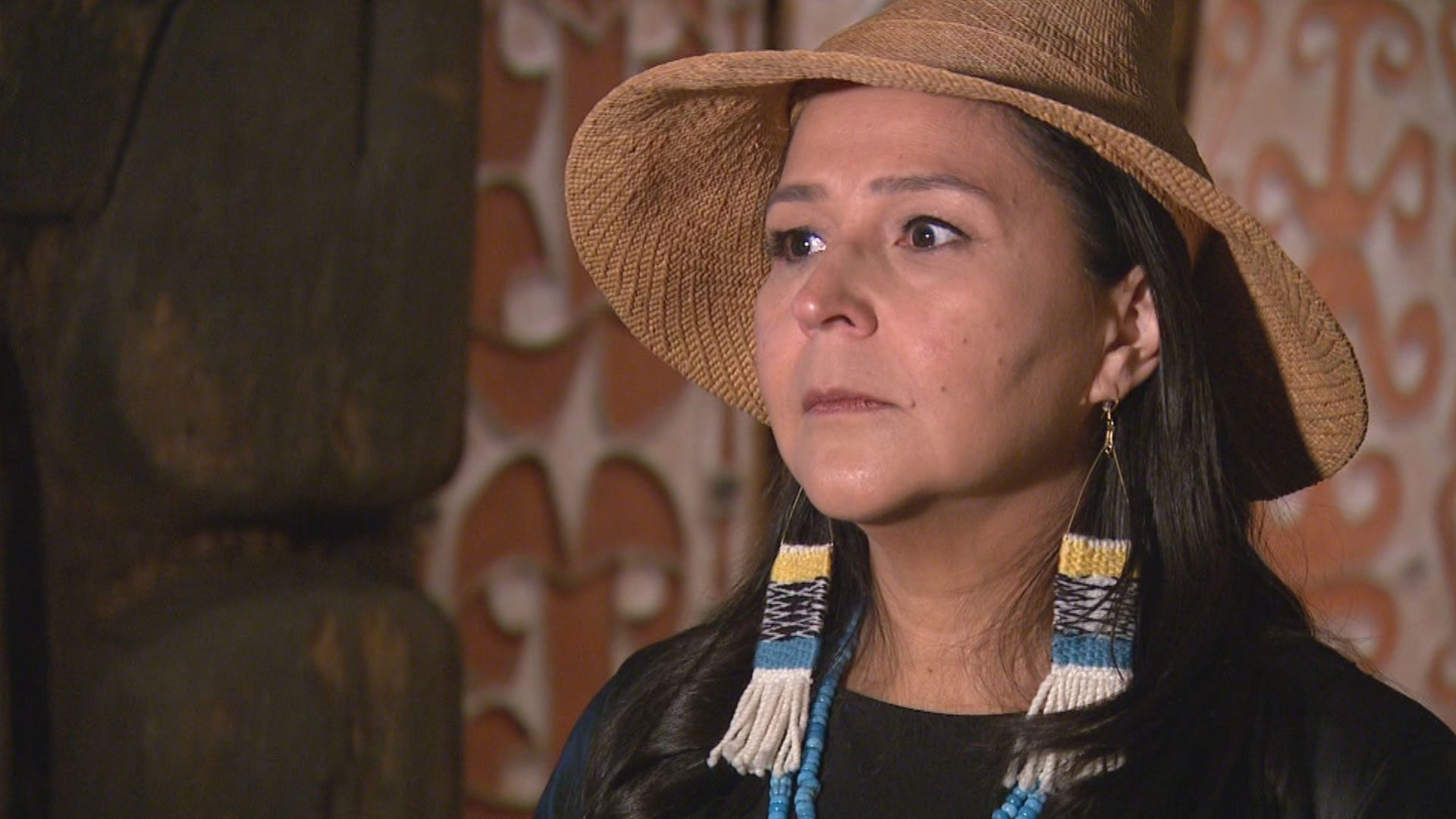

That’s when Lucy Bell, a Haida woman and the inaugural head of the Indigenous Collections and Repatriation Department, decided that after working there for three-and-a-half years, she had to quit.

And that she was going to make a speech on the way out.

“I’m going to rip the band-aid off and I hope that you have the patience and the love and the understanding to sit with me and listen,” says Bell in a video of her speech which was attended in-person and virtually. “I don’t think they knew what I was going to say, but I felt I could feel it kind of bubbling up in me.

“And I just really felt like I needed to address it and I needed to speak my own truth. So I just – in my speech, I thanked my colleagues for my learning, for the experience, but I also spoke to some of the examples where I was really hurt.”

She says it was an unpleasant experience in a meeting focused on anti-racism – organized by co-workers in the height of the Wet’suwet’en and Black Lives Matters protests – which was the final straw for Bell.

“We were all asked some questions and one of them was, ‘when did you realize you were different than other people?’” says Bell. “And one talked about native people needing to ask white people to buy their booze to stand outside the liquor store and ask white people to buy their booze because they weren’t allowed in the liquor store.

“And it really felt inappropriate. It was wrong, it was hurtful.”

Bell says afterwards she asked her boss to do something, but nothing was done, and so she quit.

Her resignation was first reported by The Globe and Mail and triggered an internal investigation and the hiring of a diversity expert, while others left as well.

“I wish it didn’t have to come to this,” says Bell. “I wish that that I was working in a place where I was respected and where Indigenous people and other people of color were truly respected. I didn’t expect to see all of this. But sometimes that’s what needs to happen.”

With repatriation in her job title, the decolonization of museums was and still is a focus for Bell.

“Decolonizing museums should not be left to the handful of Indigenous people that work in museums. It’s like it’s piled on, do my job and then decolonize the museum as well,” she says. “It’s got to be the whole institution. It has to be the people who think it’s not their job.

“They have to step up and do that as well. It means honoring and knowing what UNDRIP is and responding to the calls to the TRC.”

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), as well as the calls to action of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, are the two main reasons decolonization is a focus at museums across the country.

UNDRIP Article 12.2 says, “States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with Indigenous peoples concerned.”

And Article 15.1 says, “Indigenous peoples have the right to the dignity and diversity of their cultures, traditions, histories and aspirations which shall be appropriately reflected in education and public information.”

But the TRC gets even more specific in its Call to Action 67, which says, “We call upon the federal government to provide funding to the Canadian Museums Association to undertake, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, a national review of museum policies and best practices to determine the level of compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to make recommendations.”

Read More:

Removing the colonial lens: The push to decolonize museums in Canada

Much of Bell’s career has been focused on museum decolonization, especially the repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains.

“I helped my Haida community bring home over 500 of my ancestors,” says Bell. “And we traveled the world looking for our ancestors. And it took over 20 years, well over a million dollars of our own money to bring home our ancestors.”

Repatriation became especially important to her after an experience she had working late one night as an intern at the Royal BC Museum.

“I could hear what sounded like children playing in the stairwell,” says Bell. “And I knew that those were ancestors, the spirits of ancestors connecting with me.”

Bell’s work in repatriation culminated in a handbook on just that, co-authored with colleagues Lou-ann Neel and Nika Collison.

Their Indigenous Repatriation Handbook is available for free on the Royal BC Museum’s website and is used by communities and museums around the world.

A recent Indigenous repatriation success story is ongoing and involves the re-discovery in their collection of reel-to-reel recordings of Kwakiutl songs made early in the 20th century.

Lou-ann Neel is now the acting head of the Indigenous Collections and Repatriation Department, and she is glad the museum has a role to play in helping a community remember its songs.

Neel is from a Kawkiutl community herself and says the recordings were discovered by a descendant of a chief heard on the reels singing old songs.

“He asked if we could please digitize these reels so that he could listen to the recordings with his mom, who is a fluent speaker, and with his aunts and uncles who are also fluent speakers,” says Neel. “And so they can transcribe the songs that are apparently on these reels and when those songs are transcribed and learned, they’ll be taught to other singers in the community, especially our young ones.”

Even when it involves songs rather than physical objects, repatriation is one of the more tangible acts of decolonization in the museological realm.

And at the Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina back in December of 2020, things got particularly tangible.

That’s when a ceremony was held to return a statue stolen in India by Norman Mackenzie – who the Mackenzie is named for – about a century prior.

John G. Hampton has Chickasaw heritage and is the executive director and CEO of the Mackenzie.

A large leather-bound tomb in the gallery’s possession contains Norman Mackenzie’s accounts of his various travels, and Hampton has read the section about how the repatriated statue of the Goddess Annapurna was originally acquired.

“He was on a trip across the Asian continent at the time and was on a boat traveling down the Ganges River and came up to a ghat – the steps that lead down into that river and saw a shrine, an active shrine where people were worshiping that had three idols, three of these sculptures,” says Hampton.

“And he said that he wanted one of them and his guide told him that it’ll never happen. A Hindu will never part with their God is what he’d said. But he saw someone lurking in the shadows that, overheard him, and knew what he wanted.”

The man in shadows later came by Mackenzie’s hotel room with all three statues.

But, Hampton says, Mackenzie didn’t feel comfortable taking all of them.

“It would be a great offense to the British government,” says Hampton, paraphrasing Mackenzie’s account. “So you put back the two larger ones. And if I see they’ve been returned to their shrine, then I’ll purchase the smaller one from you.”

Fast forward a century, and Annapurna is being returned.

“It’s returning to Varanasi, which is the city that it was removed from,” says Hampton. “Annapurna has a very special relationship with that city – she’s known as the queen of Varanasi.”

Hampton says he was very moved to assist with the repatriation of the statue – and that he’s received many messages of thanks.

“We’ve gotten direct messages, emails and thanks from Indian citizens, both here in Regina and also from various places around India, just thanking us for doing that and, Prime Minister Modi did make an address to the nation,” says Hampton. “I think his words were every Indian should be proud on this day to have this object returned.”

Hampton says the Mackenzie is committed to going even further with repatriation.

“We’re doing a review on the rest of the Norman McKenzie collection, as well as the McKenzie Art Galleries collection,” says Hampton. “So there’s a few objects that we’re doing further research on. I wouldn’t make a judgment on them yet, but we are likely to see further repatriation efforts needed.”

And in 2022, the Mackenzie is planning a show that turns the colonial notion of what a museum is upside down.

In the past museums have looked at Indigenous cultures through a colonial lens.

But in an upcoming collaboration with the Art Museum at the University of Toronto called Conceptions of Whiteness, the Mackenzie will take a deep dive into what it means to be “white.”

“It looks at the origins, the travel and the mythology of this concept of a white race,” says Hampton. “So we’ve been doing a lot of research about why and when this concept of whiteness was invented, which from my understanding is it’s an invention of the 17th century and really a North American invention and a necessity for all of these Western nations that are coming to a new territory that normally would view themselves as very separate nations and not feel aligned as one like unified white culture.”

Hampton says the idea of what white means, in a racial sense, was something that was cultivated for colonialism.

“It was a tool for classifying degrees of humanity that we civilized nations that are colonizing this territory, we have a rule of civility,” says Hampton. “We’ll treat each other a certain way and respect this decorum among each other, which is distinct from the savages of this territory.”

And it is interesting, Hampton says, to revisit a remark Norman Mackenzie makes in his biography about the Indigenous people white people were trying to distinguish themselves from as North America was being colonized.

“He says he has a great respect for Indigenous people because above all other races, they have resisted being subsumed into white identity,” says Hampton. “Which is a very loaded statement and I think problematic in some ways, but also accurate in other ways, because we’ve resisted this assimilation and cultural genocide and still have our identities today.”

If Mackenzie was onto something, that strength of Indigenous identity he noted might be exactly what is needed on the road to museum decolonization.