Royce learns from his older brother Brion in how to respectfully provide for his family and community. Photo provided by Kwistunlwut Michelle Robinson.

The day before the Klahoose First Nation went into a COVID-related lockdown, Kwistunlwut Michelle Robinson and her family went hunting at Toba River off the coast of B.C.

“We arrived at Toba, and started setting up. When we went up on the little Toba River, all of a sudden this herd of elk just stepped out,” Robinson says. “They stepped out into a small clearing, right on the river’s edge.”

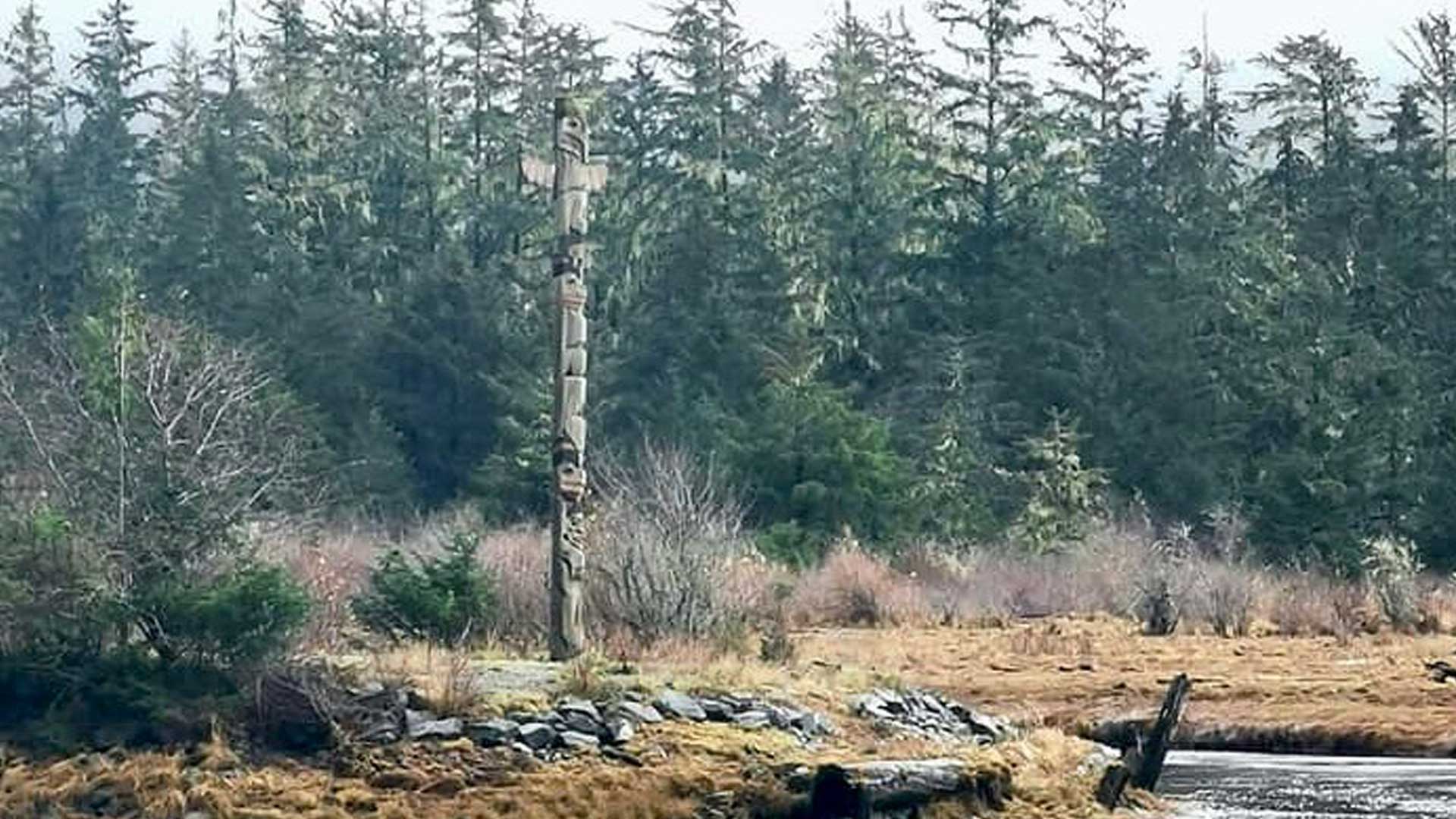

Robinson says her parents and their six children were the last family to live in Toba Inlet before they were forced to relocate.

The original village for Klahoose, whose main community is now on Cortes Island, was located at Toba Inlet, on the Toba River, she explains.

It’s a special place.

“And so my dad moved us further up,” Robinson says. “We cleared land, we lived off the land. We had to pick out every rock, it had to be immaculate. We hunted, lived in tents, and we had a little shelter we used for cooking under, and for processing food.”

Eating off of the land has always been a part of her life, and it’s a connection she has passed on to her own children.

It’s a connection that has become increasingly important to her during this year, as the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the importance of her family’s traditions and teachings, she says.

‘We know the heart of our territory’

When Robinson was growing up, she heard stories from her dad, who was raised by his grandmother and great grandmother, about when they were told they weren’t allowed to fish or hunt, “without a license,” she says.

“My grandmothers said, ‘Why should we have to pay for a license for a place that the Creator gave to us? We’ve been living here since time immemorial, since before we can remember, for thousands of years, and all of a sudden somebody comes and says you’re not allowed to fish, and you have to pay us a licensing fee to be able to feed your people.’”

Her great great grandmother Annie Hill was fined, and had to row all the way to Vancouver to pay that fine, and turn around and row back home, Robinson says.

Robinson has had to make similar trips to Vancouver, six hours by road, as well, to defend her community’s right to hunt and fish, and to work with Canada’s conservation officers and government officials, fighting for the right to do what her family and people have always known how to do.

“They were trying to dictate to us what we could and couldn’t do with our elk, like we would go up there and wipe them out or something,” she says.

“We understand what our territory lines are. We know we overlap with our sister tribes, but we know the heart of our territory. We know there are animals on it and sea life. We never over fished or over hunted, because we knew we had to keep providing for future generations.”

It has been a struggle working with outsiders, but she says her and the Klahoose First Nation council continue to build their relationship with all levels of government.

When Robinson helped organize a firearms certification program in her community, 15 members showed up, including her son, daughter, and son-in-law.

‘It’s a huge honour’

Right before the Klahoose had to go into lockdown after news of the first positive COVID-19 case, Robinson and her family were out hunting in their valley.

“We slept, got up and hunted again,” she says. “We were on a time limit, we all had to squeak the hunt in as I had to get back as soon as possible to do my part.”

They had tags for two of the elk, one for the community, and a second for Robinson’s sister who was Emergency Manager for the COVID-19 cluster response and would be busy organizing the closure.

Robinson’s youngest son would hunt on behalf of his aunt.

“He had a coming of age and he’s had to learn how to hunt. He had to learn how to clean his own deer,” she explains. “My kids have always known how to skin and process animals.”

Her oldest son Brion taught Royce, who just turned 13 years-old, how to respect his gun, and how to use it, she says. When they found out Royce’s aunt couldn’t go out on the hunt, they knew it was “kind of an initiation for him,” she says.

“We had only two days to get these two elk.”

And it was all they needed.

“The moment I see those elk step out,” says Royce. “I just thought, I’d definitely be grateful to have one of those elk and be able to get this animal to provide for my family and my community.”

“Just being in my traditional territory and being able to do all that, it’s a gift,” he says.

They weren’t just working within their own three-day window of opportunity, but they were also well aware of nature’s limitations.

“There’s only so long before a grizzly, a cougar, or a wolf picks up on that scent, because they have a great sense of smell,” Royce says. “They could pick up the scent of blood, I think around two miles. And a grizzly or even a black bear is a huge animal.”

Robinson’s older son, Brion demonstrated how to skin, cut and pack up the elk, leaving just its spine and guts to compost into the earth. Moving quickly while field dressing is a lot of work, Robinson says, and hauling out hundreds of pounds of meat, even harder.

“It was up on a huge hill, 450 yards in, and up a slope,” she says. “We had to hike in, do all the field dressing, quarter it, and pack it out.”

A hind quarter can weigh around 150 pounds, and Royce carried one out on his own.

“It takes lots of work to do all that, especially in these clear cuts, there’s lots of stumps, shrubs and roots that get caught on everything and, that just makes it so much more work to get it all over those,” Robinson explains.

The family helped in packing the meat out, and while they were excited, they also stayed focused.

“You’ve got to pay attention to the surroundings, because cougars and bears and all the predator animals out there could stalk you super easy and you just got to be ready for that,” Royce says. “You got to make sure you know what you’re doing, or things can obviously go wrong, if you don’t.”

Royce acknowledges the hard work it takes to provide for his community, and says he has a deeper understanding beyond just the activity itself.

“It’s a huge honour to put your hands into doing all that stuff. Like one second, you see this huge, beautiful animal, and then being able to take it home and feed your family, it’s just a great honor,” he says. “I’m glad I have my family to show me how to do all that.”

Land as flesh

Robinson shot her first deer during the same trip, to give to her community. They brought home two elk and five deer.

There was good medicine on this trip, says Robisnon. Returning to the valley she grew up in, to hunt with her own family during this very particular moment in time.

“It was like walking over my own ghost, because I’m walking in areas where I grew up. We used to walk those roads as kids and just to be so quiet and feel the ancestors and take steps I hadn’t taken since I was eight,” she says.

In later years, whenever Robinson missed the land, and wanted to go home to Toba, her grandmother Rose would tell her to pinch herself.

“Pinch yourself. You ate off the land and that land is now part of your flesh. Take of your own land and make it become the flesh of your child and that land will forever call to your child,” Robinson remembers the teaching of her grandmother.

This hunting trip included a visit to the graveyard and to her father who asked for his ashes to be brought home to Toba when he passed 6 years ago.

“I was raised to burn for my ancestors and for the ones that have passed,” says Robinson.

“I burned with a thankfulness for the strength that we are able to be alive today, for everything they went through good and bad — that they survived, that we could survive, and that they shared those teachings with us and the ability to hunt.”

It was a powerful moment for Robinson.

“Not everything was robbed from us and know that if you teach with love and you’re able to carry those things forward, our youth will do it,” she says. “It was really healing, just a really powerful moment for my whole family.”

She thanks the ancestors and the Creator, and she gives thanks for the teachings that were carried on.

“I knew my ancestors were watching over us and making sure nothing went wrong,” says Royce. “Bringing the animal to us and I think they were, they were definitely happy too, we were burning them a plate of food and that’s when the rainbow went over the cemetery.”