Editor’s note: Trina Roache was one of three Indigenous journalists working in Canada – and one of eight from around the world – who was invited to the Global Investigative Journalism Network’s (GIJN) annual conference in Hamburg, Germany in late September. As part of the GIJN’s first-ever Indigenous fellowship, the organization asked recipients to write an article about their experiences at the conference.

Journalism can be a solitary endeavor.

I’ve spent most of my career working in a small bureau, wandering around Mi’kmaq and Wolastoq territories with a TV camera, telling stories solely focused on Indigenous issues. (And loving it. No complaints here.)

But walking into the Global Investigative Journalism (GJIN) conference in Hamburg, Germany with 1,700 other journalists was both daunting and eye-opening.

This was the 11th year for the conference and the first time there was an Indigenous fellowship which brought together journalists from eight countries, including Australia, Mexico, the United States and Canada.

Despite the different nations, geographies and cultures represented at the table, the similarity in the impacts of colonization that weave through our stories was striking.

I listened to the issues and concerns from my corner of Mi’kma’ki echoed across continents: over-incarceration, missing and murdered Indigenous women, police accountability, racism, rights, and the Indigenous efforts to protect and reclaim traditional lands.

But I also heard similar themes of cultural resurgence and resilience.

Over the course of the fellowship, several issues became key discussion points for the investigative journalists covering Indigenous communities.

First is the importance of context.

A story on the child welfare system, addictions, or over-incarceration requires a deeper look into the history behind those statistics; the impact of residential schools, the ’60s Scoop and the Indian Act.

In European cities like the conference setting in Hamburg, history is visible, tangible, set in stone in buildings that still bear the patchwork scars of world wars.

People meander through memorials that celebrate heroes and honour those who have suffered.

In Canada, the timelines in history books often note a date 10,000 years ago or so as some sort of Indigenous marker, and then flat-line to the start of colonization. When in fact, there were thriving cultures and economies interacting and evolving that whole time.

And colonization often leaves its mark on Indigenous populations in a way not visible to the Canadian eye.

It becomes necessary for us as journalists to connect those dots for the audience. To point out that suicide rates can be rooted in trauma reaching back generations. That Indigenous languages and ceremony exist today in spite of that historical trauma.

Canadian Cree journalist Connie Walker spoke about the flexibility of the podcast format to allow that time to bring in contextual elements in the storytelling, which is often difficult to do in shorter news segments.

(CBC reporter Connie Walker delivers at talk at the journalism conference in Hamburg. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

In her award-winning podcast for CBC, Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo, Walker was able to give listeners an understanding of how past government programs and institutions, like the ’60s Scoop and residential schools, impact generations of Indigenous families.

And by hiding the history lesson in the popular “true crime” podcast format, Walker was able to reach a much wider audience.

We need an audience

In an era of dwindling TV subscribers and folding newspapers, the challenge for Investigative journalists is to make people care about the stories we’re so passionate about.

When the stories are focused on an Indigenous group that makes up roughly five per cent of the population, there’s an added challenge.

Allan Clarke, a Muruwari journalist working for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), had success with his compelling true crime podcast, Blood on the Tracks.

Clarke spent years investigating the 1988 death of a young Indigenous man, a case ignored by police and by mainstream media.

The story unfolded in TV segments, online web stories and in an interactive video of the 30 year old crime scene.

Since Idle No More, the Canadian mainstream media has been more attentive to Indigenous stories but then we head into a whole other set of issues around trauma-informed, responsible reporting.

Some of the stories we tell as Indigenous journalists are about sensitive topics and vulnerable people.

There’s a trust relationship that has to be built and maintained with people in the communities we cover.

While media can parachute in, extract a headline, and leave, the people we’ve interviewed have to live with the repercussions of our coverage.

And if we’re only covering crises, we’re missing a multitude of other stories happening in Indigenous communities.

It’s not all gloom and doom

Even in stories that might start with alarming statistics, there are nuances, context, and Indigenous experts taking action.

Capturing that story paints a very different picture from the “passive Indigenous victim/white saviour” trope that appears in so much media coverage.

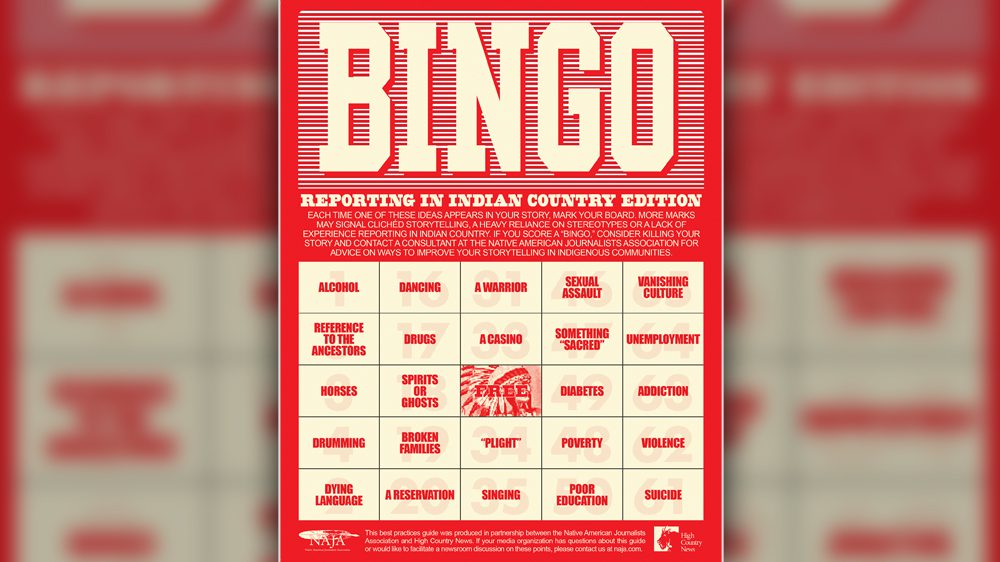

The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) has a helpful tool. It developed a Bingo card to help newsrooms avoid stereotypes. If a story is hitting too many squares on the board, such as alcoholism, drumming, violence, or addiction…ditch the story.

Tristan Ahtone is a member of the Kiowa Tribe in the United States, associate editor for tribal affairs at High Country News and president of NAJA.

In his role with NAJA, Ahtone teamed up with the Global investigative Journalism Network to produce a guide for reporting on Indigenous stories.

The guide offers information and insight into key research areas including missing and murdered Indigenous women, climate change, and data journalism.

And data was another focus of the GIJN Indigenous fellowship, and the conference at large.

Data journalism requires a skill set increasingly in demand in newsrooms.

The challenge for Indigenous journalism is a lack of data at an institutional level, or difficulty accessing that information from tribal organizations.

Indigenous fellow Lorena Allam is the Indigenous affairs editor for the newspaper The Guardian in Australia.

She led a team reporting on a story about an Indigenous death in police custody. But the wider statistics didn’t exist.

Allam and her team had to create the data set themselves, investigating deaths in custody over a decade long period.

Tristna Ahtone touches on the lack of data in a Q&A session at the conference .

“Government data doesn’t always reflect what’s going on in our communities in a more three-dimensional sense,” Ahtone tells GIJN’s Leonie Kijewski. “I’d like to know more about household makeup, for instance. How many people are stay-at-home parents? Just little things like that really help us to figure out more about what’s going on in Indian country.

“Because again, mostly it’s drug use, it’s death rates, it’s poverty rates. And while they offer some interesting data points, they do not offer a full picture.”

While some of the fellows at the GIJN conference in Hamburg work in mainstream newsrooms and part of their battle is to tell Indigenous stories in the first place, I’m fortunate to work for APTN.

All of our stories are about Indigenous issues.

Over time, hopefully, we are offering that full picture in stories that range from past traumas, to the Mi’kmaw history of hockey, housing and police accountability.

Read More:

Survivors of Duck Bay school fighting for recognition for historic allegations of abuse

Mi’kmaw connections to hockey go back to the beginning

Living in shacks and under boats: Nunavut’s billion dollar housing problem

‘I’m afraid of the guys with guns’: Saskatoon police vs Indigenous people

One of the goals of the fellowship is to network. To connect Indigenous reporters across the globe. It opens the door to future collaborations. From my corner of the world in Mi’kma’ki, it’s an exciting opportunity to contribute to an important body of work happening around the globe.

My message today as a mikmaq woman coming from n seeing my own family n other ppl as well, come fr a home that has been torn fr the government , indian affairs. The 60s scoop. My father n his other 5 siblings got taken away fr their families. It effected my home growing up n listening n seeing the tramua out comes. My whole family got torn. Thank god my granfather fr my mothers side . got saved because my grandfather told those men, that he can fend for his children. So he went out n got 2 jobs n had his family helping him to raise his daughters. My mother had 6 other sisters. 7 daughters. N he proved to be fit too show he was able to care for them n he did. But on the other hand on my dads side. 6 of them got taken fr my grandmother n put into the residential school. When they were allowed to go home, finally after 8 to 10 yrs being in that school n away fr his family. Was a tragic storey. They were already ruined. N one of my uncles committed suicide!!! Etc. It doesnt end there.