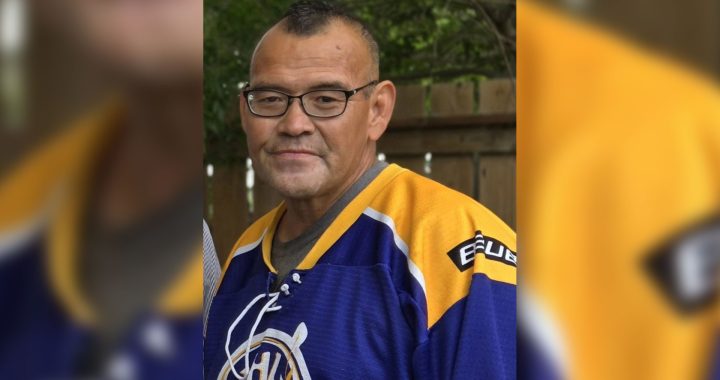

Mi’kmaq fisherman Cody Caplin is shown in a handout photo. Caplin is expected to appear today in a northern New Brunswick courtroom, where he will launch a constitutional challenge that could prove pivotal for First Nations across the Maritimes. Courtesy The Canadian Press.

A Mi’kmaq fisherman appeared Thursday in a northern New Brunswick courtroom where he began a constitutional challenge that could prove pivotal for First Nations across the Maritimes.

Cody Caplin, a member of the Eel River Bar First Nation, was fishing for lobster in the Bay of Chaleur in September 2018 when he and his brother Kyle were arrested and their boat was seized by federal fisheries officers. A year later, they were charged with 10 fishing offences, including trapping lobster out of season.

Caplin said his brother eventually pleaded guilty to the charges, mainly because of the financial burden of going to trial. But Caplin has pressed on, claiming the Mi’kmaq have constitutionally protected Indigenous and treaty rights to fish and hunt to feed themselves whenever they want.

“If we win, we could set a precedent and make some case law for other Mi’kmaq fishermen throughout the province,” he said in a recent interview, confirming that constitutional arguments will be heard at the provincial court in Campbellton, N.B.

Wayne MacKay, a professor emeritus of law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, said Caplin’s case and others like it are important because they are raising questions about the federal government’s commitment to advance reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous population.

“One would hope that after all this time … the law and the constitutional framework around the Aboriginal fisheries should be clearer,” MacKay said in an interview. “To a large extent, it’s not.”

In a statement prepared for the court, Caplin cited the Peace and Friendship Treaties signed by the Mi’kmaq and the British Crown in the 1700s, which recognize the Indigenous right to hunt and fish for personal subsistence.

“This was an obvious and basic right, as hunting and fishing for our subsistence has been how our people have always survived, since time immemorial,” the statement said. A treaty from 1752 says, “It is agreed that the said Tribe of Indians shall not be hindered from, but have free liberty of hunting and fishing as usual.”

The statement asserts that the treaties were undermined by the inherent racism in the Indian Act of 1876, which created the reserve system and the removal of Mi’kmaq people from their unceded lands to “destroy our ability to sustain ourselves.”

Caplin is also expected to cite the Supreme Court of Canada decision regarding Ronald Sparrow, a member of the Musqueam First Nation in British Columbia who was convicted of fishing illegally in 1984. In 1990, the court quashed the conviction and agreed that his ancestral right to fish was protected by Section 35 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which affirms existing Indigenous and treaty rights.

The decision allows First Nations to fish outside the regular commercial season to feed their communities or to supply ceremonial gatherings. But they can’t sell what they catch during what has become known as the food, social and ceremonial fishery.

Caplin said he had no plans to sell his catch on the day he was arrested, so his actions should have benefited from the protections offered to the food, social and ceremonial fishery.

His strategy in the courtroom will be guided by Del Riley, the former head of the National Indian Brotherhood, which Riley helped transform into the Assembly of First Nations in the early 1980s.

Between 1980 and 1982, Riley also led efforts to entrench Indigenous rights in the Constitution. He is credited with negotiating the inclusion of Section 35 in the Charter, as well as Section 25, which protects Indigenous and treaty rights from being repealed or diminished by other parts of the Constitution.

Riley, a member of the Chippewas of the Thames near London, Ont., isn’t a lawyer. He will be acting as Caplin’s agent during the hearings while Caplin represents himself in court.

“We want to do a thorough job on what their rights really are,” Riley said in an interview, referring to the Mi’kmaq. “As a nation, they have constitutionally protected rights within their treaty. And there’s a lot of issues that have to be resolved because nobody sat down with them.”

The federal Fisheries Department did not respond to a request for comment on Caplin’s case.

The case is similar to others in the Maritimes. The federal department, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, also known as DFO, confirmed last month that 54 Mi’kmaw harvesters were facing fisheries-related charges in Nova Scotia. At the time, about half of them said they were planning their own constitutional challenges, though several have since given up.

Many of the Nova Scotia cases, however, are focused on Mi’kmaw fishers seeking to earn a “moderate livelihood,” as defined by the Supreme Court of Canada’s Marshall decision in 1999, rather than fishing for food and ceremonial purposes.

Whether it’s a fishery for food or to earn a moderate livelihood, Dalhousie’s MacKay said one of the key questions is whether the federal government can regulate the seasons.

“The Supreme Court has been clear in saying that if conservation is an issue, the (fisheries) can be regulated and need to be regulated,” he said. “(But) the Aboriginal people are arguing that that kind of regulation takes away from their inherent rights to regulate their own fishery.”

MacKay said it’s almost inevitable that one of these cases will make its way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

After Thursday’s hearing, Caplin’s case was adjourned until Jan. 18.

Story by Michael MacDonald.