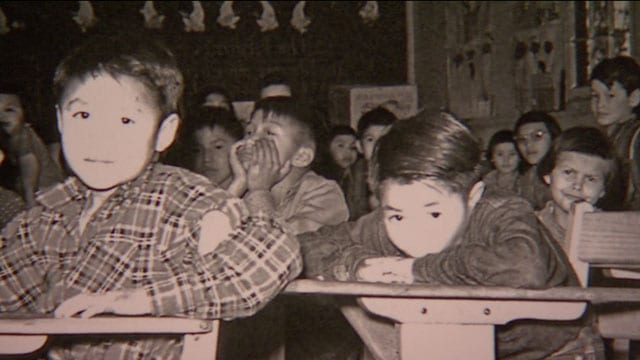

Photo from St. Anne's Indian Residential School. Undated. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Day school survivors may be promised an easier time obtaining compensation under a proposed national settlement agreement but critics say they still need a lawyer of their choice.

“Even if it’s a paper-filing process people will still need access to legal counsel,” said Lisa Abbott, an Indigenous lawyer in Saskatoon.

“Without assistance, the paper-filing process is going to be re-traumatizing.”

Abbott is one of several lawyers with experience representing residential school survivors in the Independent Assessment Process (IAP), who are voicing concerns about the McLean Day School settlement announced by Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett last week.

The IAP was the compensation portion for serious physical and sexual abuse under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

The day school agreement, which was designed by the law firm Gowling WLG and subject to court approval in May, is proposing compensation in the range of $10,000 to $200,000.

But doesn’t include an IAP-type adjudication hearing.

Instead, survivors will fill out forms and submit supporting documents and witness statements.

They also have the option of making a video statement, said Jeremy Bouchard, a lawyer and partner at Gowling in Ottawa.

“What really drove us in designing this process is we really wanted to make it as user friendly as possible,” he said in a telephone interview Friday.

“A presumption of honesty that people who are making claims are providing information that is factually accurate has been built into the process.”

But Abbott, who represented 500 IAP claimants, thinks that will short-change survivors.

Register here www.indiandayschools.com

“Some people found the hearing process was healing,” she said of the IAP hearings. “Telling their story – for some people – that was the first step in healing.”

Nick Racine, another lawyer from Saskatoon who represented 300 IAP clients, agreed, and chastised Gowling for “demonizing” the IAP.

“Garnering support for the proposed day school agreement – it should not include fear-mongering and misinformation,” Racine said.

He acknowledged the IAP did “have its faults,” but said it was lawyers that claimants “did not know and did not trust on a personal level” that failed them, and not the system itself.

“Here, we have a process being proposed that severely limits claimants ability to have the direct, personal assistance of a lawyer they know and trust,” Racine said.

Both Racine and Abbott wonder about mental health support for survivors before, during and after they apply for compensation – especially if a claimant is working alone.

They also worry claimants will be rushed through the one-year process compared to the five-year window for the IAP.

And, they insist individual lawyers are needed to ensure claimants get the compensation they deserve.

FILLING OUT A FORM

“They’re filling out a form that is asking them very specific, detailed questions that takes them back to a time in their life when they were physically, emotionally and sexually abused,” said Racine.

“They should do that with a lawyer who understands the legalese of the language in the application who has the ability to put them in contact with health support in the community.”

Racine said he made sure to meet in person with residential school claimants who suffered sexual abuse.

“I had the ability to monitor where my client was at all times during disclosure. It’s very important that when you take them to a place of trauma – you bring them in and you bring them out in as safe as manner as possible.”

Bouchard said Gowling is open to hearing concerns and incorporating them into the agreement.

But some things need the personal touch of a lawyer, argued Abbott.

“In this process, the average complainant… will have a Grade 6 education,” she said, “and to have someone fill out a form by themselves with five very, defined types of (harmful) acts… will be re-traumatizing.”

Abbott doesn’t believe one firm – Gowling – can handle all of the estimated 130,000 claims.

Nor, said Racine, is there incentive for Gowling “to assist people with their claims and make them as successful as possible” when it will receive $55 million 30 days after the settlement is approved.

“This is a great process for the government,” added Racine, an Indigenous lawyer in Saskatoon.

“The amount of legal fees that they’re paying – if you do the numbers on it – it’s less than $1,000 in legal fees per claim.”

Read: Notice of Certification and Settlement Approval Hearing documents

Racine said he’s “passionate about” wanting the ability to represent claimants who know and trust him “with their stories.”

Instead, he fears they will go through a process where Gowling “is doing everything possible to limit the contact individual claimants have with class counsel.”

Bouchard, a Mohawk from Six Nations of the Grand River, agreed the day school settlement is “fundamentally” different from the residential schools settlement.

“It is a paper-based process that is claimant-friendly, non-adversarial, and meant to be completed with very little outside or third-party assistance.”

He said Gowling lawyers travelled the country to hear first-hand what survivors wanted and reflected that in the settlement.

See the registration form here.

“We wanted to do it differently…get out to communities before, meet with communities, meet with leadership, meet with the people.”

Bouchard said that’s why the application process is only one year and has reduced the number of lawyers involved.

“A lot of people just felt they got lost, they got re-traumatized,” he said.

“Claimants could navigate their way through this – by themselves if they chose to – but with resources available it would not be as lengthy as the IRSSA process and would not re-traumatize and harm individuals.”

Lastly, Bouchard said Gowling did its best to seek a balance between those who want to tell their stories and those who want to “limit their interaction with government lawyers and officials.”

So, along with the video statement option, he said $200 million from Canada for legacy, healing and commemorative events will offer a “truth-telling forum.”

He said these could take the form of national and regional events where survivors could share and document their experiences.

“We understand that people will want to tell their stories. And we think that there’s an educational component to this, too,” Bouchard said.

“Everyone needs to know that the abuse, the harm, that happened in federal Indian day schools were similar to what happened in Indian residential schools.”