It’s a place few have even heard of, and even fewer will get to visit.

But thanks to new a virtual reality project, “Qikiqtaruk: Arctic at Risk,” people from around the world will now get the opportunity to see how climate change is impacting the Canadian Arctic first-hand.

The virtual project transports viewers to Qikiqtaruk, a remote 116-square-kilometre island located five kilometres off Yukon’s northern coast in the Beaufort Sea.

Also known as Herschel Island, Qikiqtaruk has ancestral ties to the Inuvialuit who continue to use the site for traditional activities. Its also home to a few historic structures used by 19th century whalers, as well as a former RCMP building and a handful of graveyards.

Today the island is a protected territorial park under the Inuvialuit Final Agreement and is a popular destination for researchers and a few hundred tourists who visit each year.

Senior Park Ranger Richard Gordon, who is Inuvialuit, has spent much of his two-decades plus career monitoring Qikiqtaruk’s landscape. Over the years he’s witnessed many changes to the Arctic island, like intense erosion on its coastal cliffs, leading to a troubling release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

“It really opens your mind to think, why is this happening?” he said.

Gordon, who lent his voice to the project as one of its narrators, is hopeful it will enhance people’s understanding about what’s happening on the island.

“I think it’s a very important project,” he said. “With today’s climate change, how fast is this happening? How big of an affect is it going to have in the future and how that affect has on the plans, the island itself and the wildlife and fish in the area?”

Read More:

Climate change and Tuktoyaktuk: A community’s front row seat to a changing world

Project lead Isla Myers-Smith, who is a professor of Climate Change and Ecology at the University of British Columbia, has been studying the island since 2008.

She said the project was born from the COVID-19 pandemic as she and other researchers were unable to travel to the island and were unsure what to do with data they were collecting.

“VR is a cool and emerging technology,” she said. “The tech itself is still developing, but what it can do is give you that immersive experience of an environment if you can’t go there yourself.”

Thanks to funding from the National Geographic Society, she and other scientists were able to create a virtual experience that could take viewers to the island using real sound and drone footage collected from the field.

As the island is only accessible by plane or boat, Myers-Smith said the experience even allows for local Inuvialuit who otherwise are unable to visit to see the landscape for themselves.

“We wanted a way to communicate what’s going on that’s more engaging than the scientific papers that we publish and that could transport people there,” she said.

The project explores several changes happening to the island, like an increase in invasive shrubs that’s suffocating the island’s native plants and rising sea levels that are threatening to swallow historic buildings.

“(We wanted something that could) take (audiences) back in time to what it might have looked like in the past, through to the current day, but also into the future to think about what it might look like if these changes play out,” Myers-Smith said.

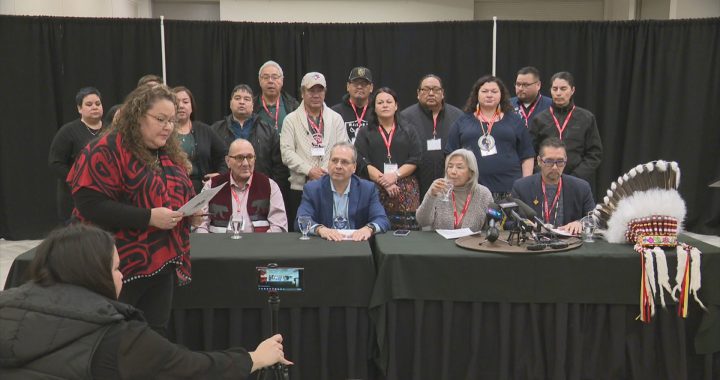

The project was recently shown to youth and community members in Aklavik, N.W.T. Myers-Smith said her team will implement community input into the final version once its officially debuted this coming winter.

With the island’s future in jeopardy, Gordon is hopeful the project will serve as a tool for educating young Invuilait about the island’s importance.

“They too have a voice in protecting their culture.”