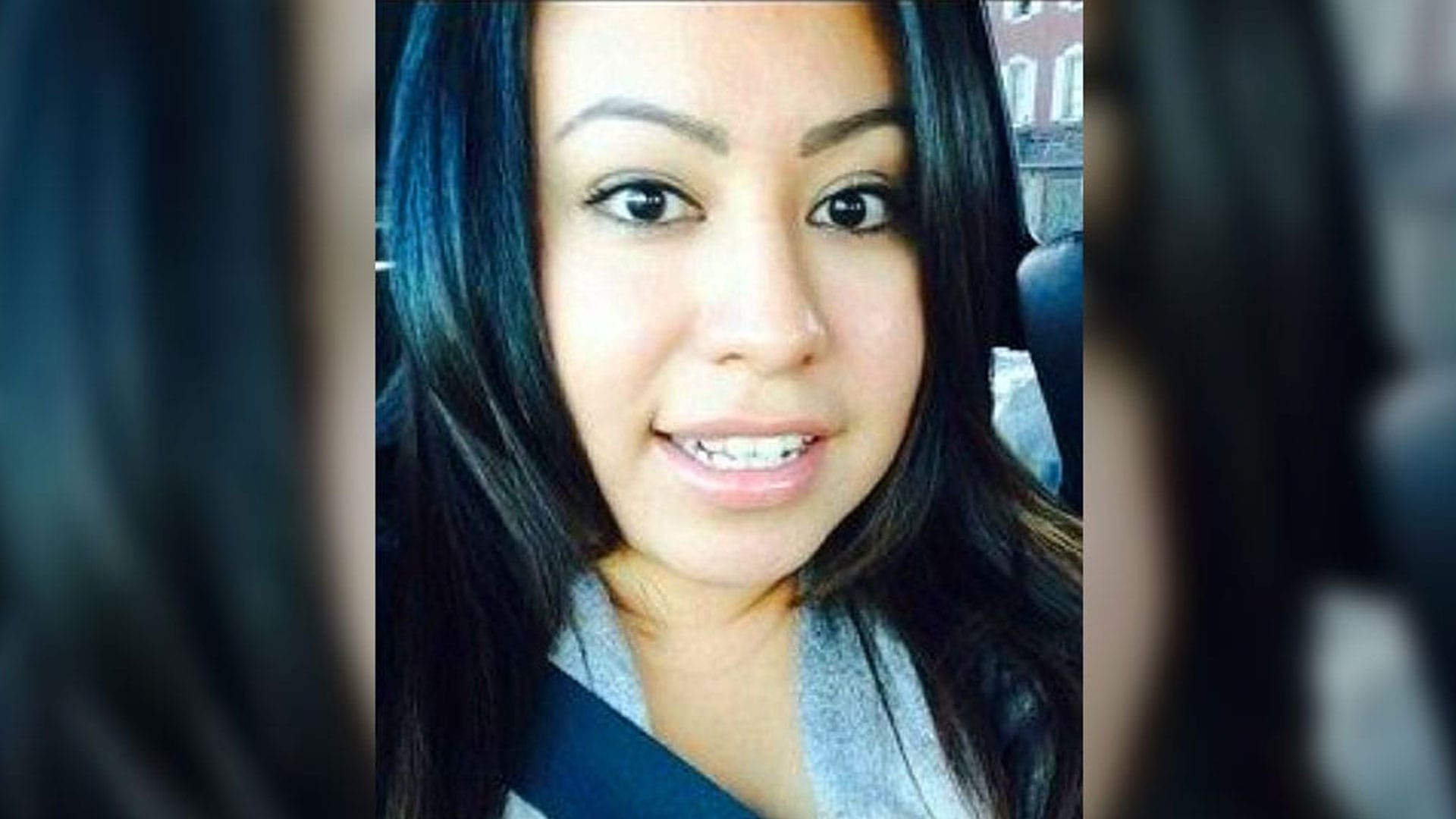

Caitlin Potts of Alberta is a missing First Nations woman. Photo: Facebook

A new law on the books in three Canadian provinces will make it easier to find out if an intimate partner has a history of abusive behaviour.

So far the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme, also known as Clare’s Law, is available in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

“You always hear about the warning signs, the ‘should have known’,” said Const. Joelle Nyeman, the RCMP’s relationship violence co-ordinator in Regina.

“Now this law can cover off ‘I should have known’ to ‘I now know’ – so I can make that informed decision.”

Clare’s Law is named for Clare Wood, a woman murdered in England by a former boyfriend in 2009 who police knew to be dangerous.

It is intended to reduce intimate partner violence.

The law was adopted in England and Wales in 2014, before expanding to parts of Australia and Canada.

Here’s how it works: Domestic partners can fill out a Clare’s Law application for a history of their partner’s relationship violence. There is no charge for the information.

Police can disclose allegations, convictions, and even peace bonds (also known as restraining or protection orders) from jurisdictions across Canada. Contact with police that didn’t lead to arrest or charges can also be shared.

The information is vetted by an internal committee before being released on a case-by-case basis, Nyeman noted.

Priscilla Potts, whose daughter Caitlin Potts was last seen in Kelowna, B.C. in 2016, said she would have used Clare’s Law.

She hopes to see it expand across Canada so parents like her of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls can take advantage of it.

“If you want to know about somebody’s violent history, you do whatever it takes,” said Priscilla via phone.

Caitlin was 27 and living with a boyfriend in Enderby, B.C., when she vanished. She was originally from Samson Cree First Nation in Alberta. RCMP said they suspected foul play in her disappearance.

Some municipal police forces provide Clare’s Law applications online but RCMP require applicants to call the non-emergency line or come to the detachment in person.

“If they’re worried that possibly their partner would see them go to the detachment (then) we can make alternate arrangements,” said Nyeman, noting communication can be done via WhatsApp – an online messaging platform.

“We want to make as little barriers as possible for people to go ahead and make these applications.”

‘Right to ask’

Clare’s Law has two components: the ‘right to ask’ and the ‘right to know’.

The ‘right to ask’ allows domestic partners and certain third parties to request information from police about a potential abuser; the ‘right to know’ permits police to disclose such information, under certain circumstances, to member of the public on their own.

Nyeman said information would be shared verbally with applicants who are instructed not to post it online, and could take up to 30 days to turn around.

She said the level of risk would be characterized as low, medium or high.

“We will never say that there’s no risk,” she added, “because if you’re coming into the police station (you) had some warning signs, some red flags going up.”

There were no Clare’s Law applications filed yet with RCMP in Saskatchewan – the first province in Canada to enact the law.

But municipal forces in Saskatchewan have already received approximately 10 applications, Nyeman said.

She said Clare’s Law is not available to corporate or political organizations.

Meanwhile, the RCMP say its members are ready to receive Clare’s Law applications across Canada once more provinces enact legislation.