There are few cars in the small village of Haines Junction, Yukon.

But as the man behind the community’s Southern Tutchone video road reports will tell you, every word of these reports is worth speaking.

The report’s announcer, Khâsha, is from Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN).

Once a month or so, Khâsha perches himself on a bench across from the main strip of highway that runs through Haines Junction and films himself commenting on the vehicles, animals and people he sees in dän k’e, the Southern Tutchone word for the language.

Afterwards, he uploads the videos to Youtube with Southern Tutchone and English subtitles.

The videos are often humorous; in one video, Khâsha happily encourages truck drivers to honk their horns; in another, he remarks how the clouds “look like a moose’s stomach.”

He said the inspiration came from the character of Chief Leonard George in the 1998 Native American drama-comedy Smoke Signals.

“He makes these weather report videos and they’re hilarious,” Khâsha chuckles.

“(Humor) is the foundation level of learning language. The point is to laugh and bring our defences down and be comfortable. I think so many people have the opposite experience in schools where grammar is pushed on you.”

While the videos are a fun and interesting way to learn Southern Tutchone, they’re also a channel to preserve a language that’s rapidly vanishing.

Fighting to keep a dying language alive

With every passing of an elder, the language goes with them, and Khâsha estimates there are fewer than 20 Southern Tutchone speakers in the community.

Now, he’s made it his mission to pass on the language so that it may be preserved for future generations.

“My vision is very clear on what I’m doing. It’s paramount for survival, and survival of our people,” he said.

Khâsha grew up as Stephen Reid, and while his grandmother spoke the language, he had few opportunities in learning his ancestral tongue until he attended university.

“For the first time I started learning about the true history of Indigenous people in Canada, and things that were never talked about in school. That summer I went home and looked at the community, and went ‘where are the younger speakers?’”

Alarmed, Khâsha began learning the language from his grandmother, and has since earned a degree in education and a masters in language revitalization.

Now 41 and going by his traditional name, Khâsha describes himself as moderately proficient, and for the last three years has been teaching a one-of-its-kind immersive language program to a cohort of eight adult students at the Da Kų Cultural Centre in Haines Junction.

He said it’s those who want to see tradition carried on that’s compelled him to do the work.

“I think it started with a vision, and the vision came from the ancestors. I was able to glimpse that vision through the teachings of the elders. Just like my mind tells my hand what to do, the ancestors tell me what to do, and I’m the working hand of the ancestors.”

The full day classes heavily focus on speaking, and the only goal of the program is for students to gain language proficiency. Eventually, some students will even pass on the language to children at a local daycare.

Khâsha said so far, results are promising.

“Our younger students are hungry for the language. It’s redirected their lives. A lot of the things that are being transmitted to the students is in our teachings.”

An immersive program

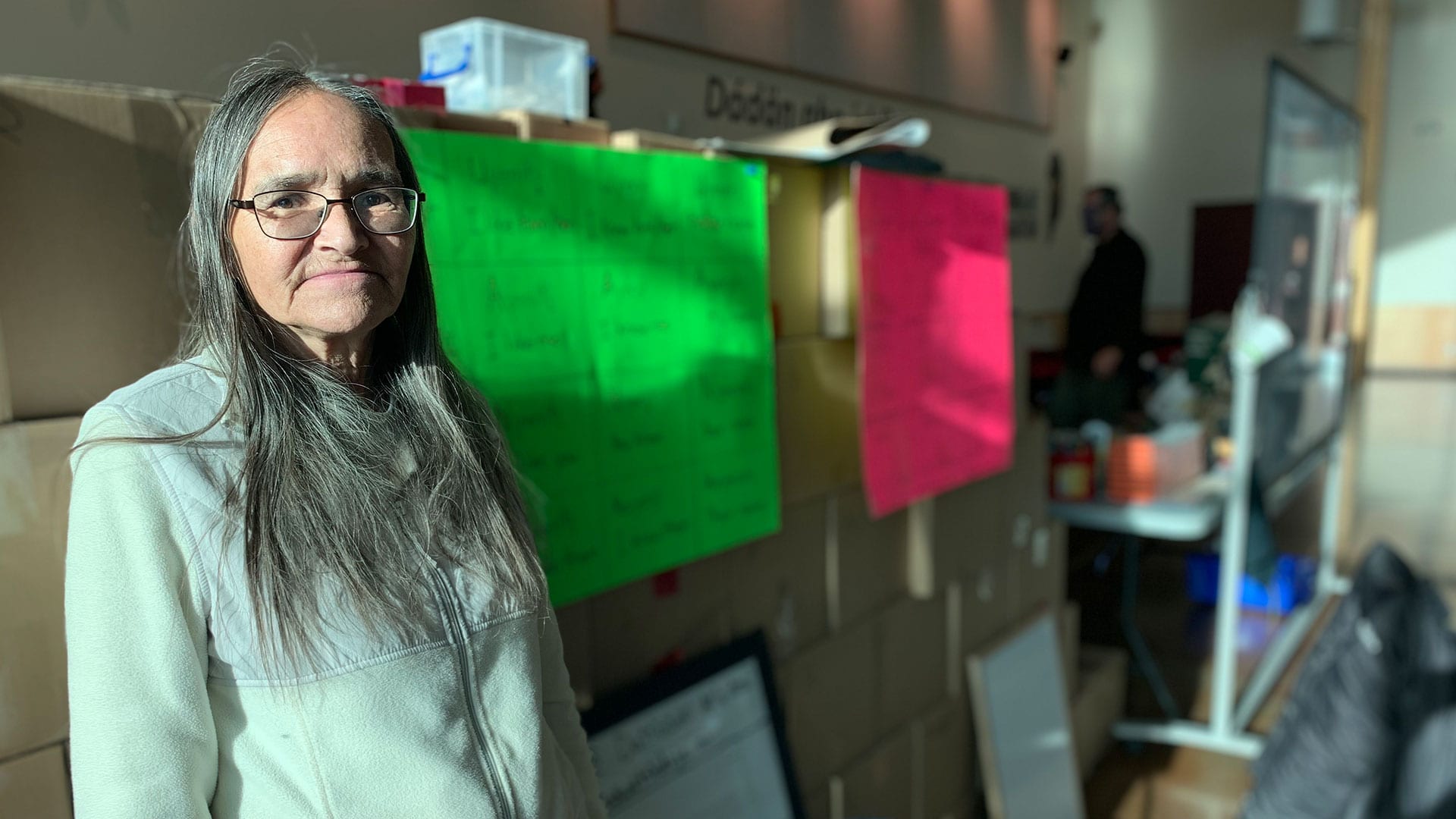

Sheila Kushniruk is one of the oldest students, and works at the Da Kų interpretive centre.

She’s learning the language to enhance her interpretive work.

Growing up in and out of foster homes, Kushniruk said she never got the chance to learn her language.

Now, she plans on passing on what she’s learned to the next generation – something she never thought she’d be able to do.

“When I’m talking to my grandkids, I can understand when they’re asking me questions,” she said.

A few days a week, two elders also attend classes and reinforce the language by teaching cultural practises that most students haven’t had the opportunity to learn, like making gopher sticks, smoking salmon and harvesting moose.

Khâsha said having elders in the classroom has been a major benefit for students.

“Our hands were bound in the school system to small chunks of time with students. With this program we have seven hours a day. We have two elders, three days a week. That one on one time with elders has been phenomenal.”

One of these elders, Lorraine Allen, came out of retirement to work at the program.

“I was thinking there isn’t many elders around now to help, to revitalize the language, so I kind of thought it was my job in my life,” she said.

Three years in, Allen said she’s seen first-hand how successful the program has been.

“We’re happy with how good the students’ progress is, they’re doing better than I thought. How I know that is cause’ when (the elders) speak to each other, they know what we’re saying. With them speaking to us in the language, too, we understand them.”

Language, ‘our way’

CAFN invested $1 million into the project, and pays students to take the program so they can focus on their studies without worrying about finances.

Chief Steve Smith said an immersive, First Nations run language program was necessary for true language acquisition.

“It’s supposed that almost $6 million a year is spent on First Nations languages in the Yukon. We haven’t seen any real movement. Kids get 20 minutes a day of Native Language class,” he said.

Smith said the idea for a language program had been in the works for years, and that a chance discussion between himself and Khâsha while he was teaching languages at an elementary school turned the idea into reality.

“The conversation led to the fact that it didn’t matter how much we actually did in schools or anything else. If we don’t start actually restocking our speakers, then any kind of language speaking program is going to wither on the lines.”

In 2017 a group from CAFN visited the Mohawk Kahnawà:ke Reserve, south of Montreal, to learn about its 17-year-old immersive language program, the Kanien’kéha Ratiwennahní:rats Adult Immersion Program.

Smith said the results were impressive, and the First Nations modelled their program after it.

With CAFN’s program producing a fairly fluent cohort of students, Smith said it’s a vibrant example of self-determination.

“‘Dun gae.’ That translates to ‘our way.’ One of the things that we made the commitment to in 2017 was we were no longer going to sit idly by and let another government run and dictate to us as to what our language program was going to look like.”

Hope for the Future

While the program was only intended to run for two years, students requested a third to better hone in on the language.

Next year they’ll graduate, and a new cohort will come in.

Word of the program’s success has spread, and there’s now a waitlist for prospective students.

“If we produce one speaker, that is a game changer for us,” Khâsha said.

“What I’m really trying to foster is this lifelong. It has to be. Even three years isn’t enough time to be where our elders need us to be.”

Khâsha warns it won’t be an easy road ahead.

“It’s challenging that our numbers are so low. It’s challenging that our community is so small. But, there’s a lot more things pushing me down that path than there are challenges.”

Read More:

Why the Yukon’s Indigenous languages are disappearing, and what’s being done to get them back

While immersive programs like CAFN’s are important, Khâsha said Indigenous languages can’t only exist in the classroom, and that they need to be spoken frequently and in everyday life like his road reports.

He said this, and investment in First Nation run language programs, is the key to preserving languages for the next generation.

“My ultimate goal would be that my grandchildren don’t have to learn Southern Tutchone, that they become speakers of it. It doesn’t have to be something that they have to dedicate their life to like I have to, it’s just something that they can have.”