The federal government, First Nations organizations, and class-action lawyers announced details of two agreements in principle Tuesday that, if ratified, could end a nearly 15-year-old legal battle over the racist underfunding of child welfare services on reserves and in the Yukon.

The deals, worth $40 billion and reached New Year’s Eve, would respectively spend $20 billion compensating tens of thousands of families victimized over the last three decades and another roughly $20 billion over five years on program reform.

It’s the largest settlement in Canadian history, Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller told reporters.

“No amount of money can reverse the harms experienced by First Nations children,” he added.

“However, historic injustices require historic reparations.”

Miller spoke at a press conference in Ottawa alongside other federal ministers, leaders from the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Chiefs of Ontario, Nishnawbe Aski Nation and legal counsel representing First Nations youth and families.

Sotos Class Actions lawyer David Sterns said the deal may be the largest settlement in the world.

“The enormity of this settlement is due to one reason and one reason only,” Sterns said, “and that is the sheer size and scope of the harm that was inflicted on the class members as a result of a cruel and discriminatory First Nations family and child welfare system.”

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, said her organization is not party to the compensation agreement, but called the draft agreement on long-term program reform a pathway to a final deal, adding that only when that deal is signed and implemented can youth be sure real change is coming.

“Nothing changes in the lives of children today,” she said during a virtual press conference after the ministers spoke. “These are simply words on paper. It is not time to look away, and it is not time for any of us to exhale.”

Once final details are negotiated, the settlement agreements and distribution plan must be approved by the court and tribunal before implementation.

A long, bitter battle

By deciding to settle out of court, the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau could resolve the long and occasionally bitter legal fight.

The AFN and Blackstock filed the original human rights complaint in 2007 alleging Indian Affairs’ funding formula for First Nations child welfare — that was known as Directive 20-1 and came into effect in 1991 — was racially discriminatory.

Cindy Woodhouse, AFN regional chief for Manitoba, reflected on the long fight and thanked the numerous AFN leaders who pressed the issue for the last 30 years.

“First Nations across Canada have had to work very hard for this day to provide redress for monumental wrongs for First Nations children, wrongs fuelled by an inherently biased system,” she said at the press conference with the ministers.

“More than 200,000 children and families are impacted by this compensation agreement. This wasn’t and isn’t about parenting; it’s, in fact, about poverty.”

The complaint also alleged Canada failed to implement Jordan’s Principle, a child-first principle supported by the House of Commons in 2007 to ensure First Nations children have access to essential health care unhindered by jurisdictional bickering between governments over who should pay.

The Canadian government under then-Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper responded with what the AFN last year called an obstructionist campaign of administrative and legal delay tactics, deflection and non-compliance.

Between 2008 and 2013, Canada motioned to have the complaint dismissed and tried to derail the process by retaliating against Blackstock, ejecting her from a meeting and spying on her.

At the same time, the Harper regime knowingly withheld more than 100,000 documents and emails it was obligated to disclose. The records, it turned out, were “prejudicial to Canada’s case and highly relevant” and the human rights tribunal scolded Canada for its “lack of transparency and blatant disregard” for the process.

Read more:

Can 5 weeks of talks settle a 14-year battle over child welfare? Here’s what has to happen

‘It’s a nightmare’: Zach Trout watched two of his children die, now he’s fighting Canada for justice

With government roadblocks in the rear-view mirror, the tribunal in 2016 issued its groundbreaking decision substantiating the complaint and vindicating the AFN, Blackstock and the other organizations that intervened.

A two-person panel ruled Canada was violating basic human rights by underfunding the racist program, which it ordered Canada immediately reform while properly implementing Jordan’s Principle.

The Liberals in 2016 — then early into their first mandate — welcomed the orders, did not appeal and promised to obey. But the hearing of the complaint wasn’t finished.

On the question of compensation, the tribunal ruled in 2019 that Canada was “devoid of caution with little to no regard to the consequences of its behavior towards First Nations children and their families.”

It was a “worst case scenario” under the Canadian Human Rights Act, the panel said.

The panel awarded the statutory maximum of $20,000 to victims and their primary caregivers along with another $20,000 because the racial discrimination was “wilful and reckless,” causing profound indignity and harm.

Ottawa failed to immediately comply after the 2016 ruling, so the tribunal issued numerous subsequent orders. Among them, the tribunal ordered Canada to extend Jordan’s Principle eligibility to certain non-status kids and pay for infrastructure the agencies need to deliver services.

Here the Liberals picked up the fight once again. The Trudeau regime applied for three judicial reviews in three years starting in 2019.

The Federal Court heard two separate reviews on the compensation and eligibility orders consecutively in spring 2021. The government was already under consistent attack from opposition political parties and continued to take heavy fire in the courtroom.

Counsel for the caring society said Canada’s “legalistic, technical and ultimately irrelevant” arguments “reflect a shameful strategy aimed at saving money at the expense of First Nations children and families.”

The AFN said Canada’s approach was “callous” and “heartless,” representing the same “paternalistic and colonial view that it knows what’s best for First Nations children” that created these systems in the first place.

While presiding Judge Paul Favel, who is Cree, was more restrained in his judgement, he sided with the tribunal nevertheless. He said it “reasonably exercised its discretion” to handle a complex case of discrimination while ensuring all issues, including compensation, were addressed fairly.

Canada responded with another appeal but promised to try and negotiate a solution by Dec. 31, 2021. Federal officials said they would only litigate if negotiations failed.

They added Tuesday they won’t drop the appeal until a final deal is ratified.

They’ve pointed in the past to the fact the tribunal order compensates victims dating back to 2006, while the class action represents plaintiffs dating back to 1991 when the policy came into effect.

A huge portion of victims wouldn’t be paid as a result of the tribunal’s decision.

All class actions settled

The lawsuit covering these individuals was first filed in 2019 by Xavier Moushoom, a 34-year-old Algonquin Anishinaabe man from Lac Simon, Que., who was scooped from his home and placed in foster care outside the community in 1996.

“To this day, he does not know the reason for his apprehension,” according to his statement of claim.

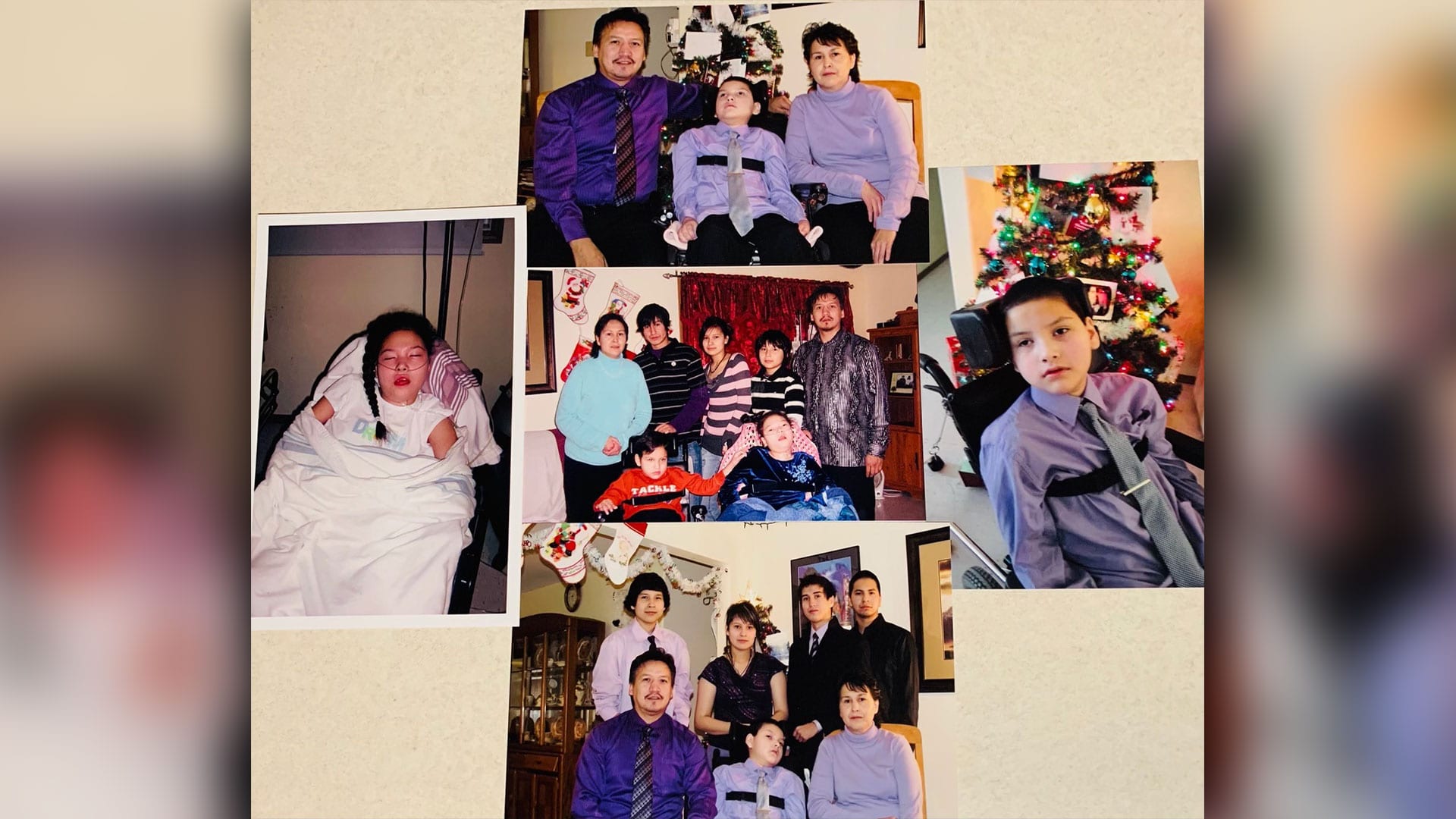

Jeremy Meawasige, from Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia, soon joined the suit to represent victims who were denied or suffered delays accessing essential services through Jordan’s Principle.

Meawasige, 27, has hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, spinal curvature and autism. He can speak few words, can’t walk without help and needs 24-hour care. He’s represented by his brother, Jonavon Meawasige, who is also a caregiver lead plaintiff.

Their mom, Maurina Beadle, who died in 2019, cared for Jeremy at their home on Pictou Landing until she suffered a stroke in 2010. The band council then paid for Jeremy’s home care after Canada refused.

Beadle and Pictou Landing took Canada to court over it, arguing that Canada’s refusal to pay the cost of in-home care violated Jordan’s Principle. They won when Federal Court Justice Leonard Mandamin, who is Anishinaabe from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, ruled in their favour in 2013.

Mandamin has since retired from the bench and was recruited as a mediator to try and reach a “global resolution” of all outstanding litigation in September 2020.

A few months prior, the AFN had filed a nearly identical competing class action. The lawsuits soon decided to combine and work together around the same time as Mandamin became the mediator.

The parties’ differing opinions on the Jordan’s Principle aspect of the lawsuit was a sticking point.

Canada maintained it had “no duty to compensate” people who were denied essential services before 2007 because that’s when the House adopted the principle.

In response, lawyers proposed to split the claim in two.

Zach Trout, of Cross Lake First Nation in northern Manitoba, was added to represent these proposed class members.

Two of his kids, Sanaye and Jacob Trout, died before age 10 from Batten disease, a rare neurological disorder that normally begins in early childhood and results in seizures, vision loss, deterioration of motor skills, cognitive impairment and, eventually, death.

Trout, in an interview with APTN News, described the suffering his family endured that was exacerbated by endless jurisdictional squabbling and bureaucratic wrangling similar to what Meawasige’s family faced.

As a result of this and other issues, the mediated talks failed to bear fruit a year later. Former senator Murray Sinclair was then brought on as a facilitator as discussions resumed with renewed vigour after Favel sided with First Nations children and their advocates in the judicial reviews.

Trout and those he represents were included in the new talks and are now included in the proposed deal.

Lawyers told the press conference Tuesday $40,000 will be the minimum for those removed from their homes, but the amount they can receive won’t be capped. It’s not clear how much money the Jordan’s Principle claimants like Trout and Meawasige will receive.

Ending policies of Indigenous child removal

Sinclair headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which probed the history and legacy of Canada’s residential schools. The commission’s first call to action was for government to immediately reduce the number of Indigenous children in state care.

The modern child welfare system’s disturbing similarities to the residential school system is something the complainants and plaintiffs pointed out several times throughout litigation.

The original complaint noted that, at the time of filing, there were more First Nations children in state custody than at the height of residential schooling in the 1940s. There are now three times as many.

Residential schools were notoriously, chronically and knowingly underfunded. Ottawa’s funding policy, which consisted of a yearly per capita grant, created a financial incentive for churches to snatch as many pupils as possible to obtain the maximum grant.

Under modern child welfare Directive 20-1, Ottawa provided a fixed and insufficient pot of cash for prevention services but fully reimbursed agencies for apprehending children and maintaining them in out-of-home care.

This “perverse incentive,” legal filings said, ensured Canada continued to scoop children from their families, homes, communities and cultures by the thousands right up to present day.

“The federal child welfare program was broken from the start,” said Woodhouse. “Most Canadians do not know this — that there was actually an incentive for child welfare agencies to remove children.”

Blackstock said the Federal Court loss coupled with the findings of unmarked graves at residentials schools presented government with a historic opportunity: Continue with an unpopular and losing litigation strategy or finally end the injustice.

“That was the choice for them,” she said.

Blackstock said the human rights complaint would be closed when the tribunal is satisfied the discrimination has ceased, and caring society counsel Sarah Clarke added the next 12 months offer ample time to get it done.