More than a year after Mi’kmaw lobster fishers were attacked on land and sea, the federal government is deliberately delaying its response to an urgent request from the United Nations (UN) based on allegations Canada failed to protect treaty harvesters from racist violence.

Documents obtained by Nation to Nation reveal Canada doesn’t recognize the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s “competence,” or jurisdiction, to consider allegations from domestic citizens and is relying on this technicality to drag its feet.

As a result, Canada is sitting on its completed response, which was drafted by six federal departments and the Nova Scotia government, and says it expects to submit it next month — more than a year after the unrest and eight months after it was initially due.

“It’s a weak move by Canada,” said Rosalie Francis, a lawyer and Sipekne’katik First Nation member who helped compose the original dispatch to the UN.

“Preventing the UN from having any kind of jurisdiction over their conduct internally is quite disingenuous,” she told N2N. “It’s contrary to their commitments to reconciliation and their emphasis on the importance of the relationship with Indigenous people.”

The international committee doesn’t have a complaints mechanism. Rather, it relies on something called an Early Warning and Urgent Action Procedure, or EWUAP. This preventative procedure is meant to stop race and hate motivated civil strife before it escalates, Francis said.

But before the committee can consider claims from alleged victims of racism, signatory states must recognize the committee’s jurisdiction to do so under Article 14 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Canada hasn’t made that declaration. Ottawa also disagrees that the committee’s numerous concerns “are situations appropriate for consideration under the EWUAP.” Canada will respond eventually but “solely as part of its regular periodic reporting to the committee.”

Francis, however, doesn’t buy this argument. She said Ottawa’s legal interpretation of the convention is dubious, if not plain wrong, and reveals a cavalier attitude toward independent human rights oversight.

“It’s all about window dressing,” she said, explaining that Canada tries to position itself as a world leader on human rights, “but when we take back the curtains and look inside the house and say, ‘Well, let’s really see what’s going on here with human rights,’ that’s where Canada starts to get a little uncomfortable.”

Read more:

Federal government agencies ‘complicit’ in violent attacks on Mi’kmaw harvesters: chief

Meanwhile, the logjammed UN response is not the only development in the fallout from the Mi’kmaw Nation’s fight for fishing rights.

In September 2020, Sipekne’katik issued its own moderate livelihood lobster tags outside the federally regulated season based on nation-to-nation treaties that are more than 250 years old.

Commercial harvesters reacted with protests and vigilante tactics. There were boat chases, a floating blockade, and a flare was shot at Mi’kmaw vessels in the first few days.

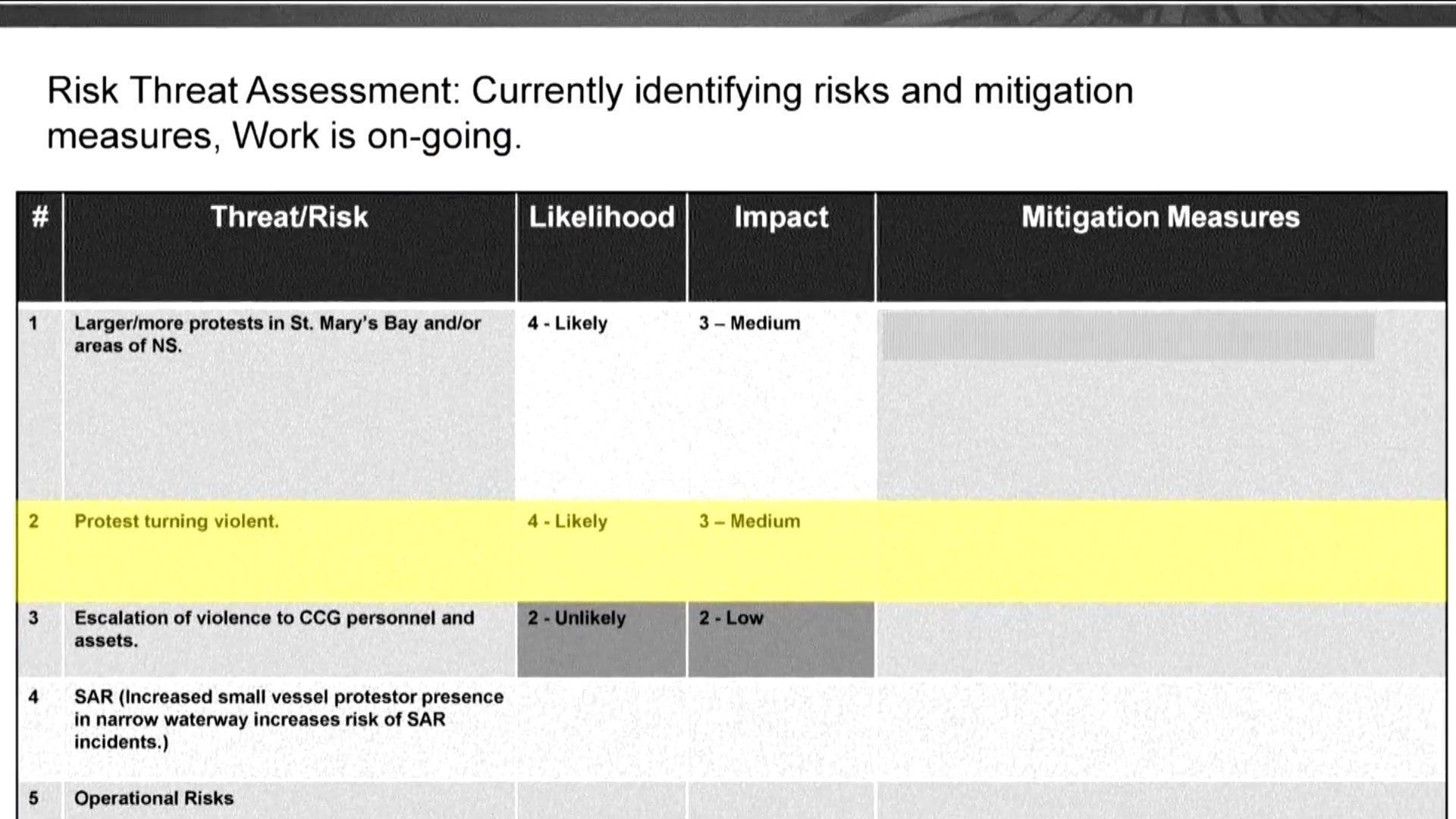

APTN News later uncovered documents that revealed federal spies with the National Fisheries Intelligence Service were closely monitoring the situation even before protests erupted.

Officials at the marine intelligence agency rated the threat of protests continuing as “likely” two days after the fishery launched, adding that it was also “likely” those protests would turn violent.

This turned out to be accurate. A month later, a mob surrounded a fish processing plant used by Mi’kmaw harvesters. Jason Marr, a community fisher, livestreamed the attack while barricaded inside.

Despite ample indication of the high risk of violence, there were few police present and those who were watched idly as the facility was ransacked. A van was set ablaze and later the fish plant itself was torched.

More than a year later, restorative justice is being used for 22 of 25 people accused of crimes, which doesn’t sit well with Sipekne’katik Chief Mike Sack. He said it’s a “cop-out” that leaves him questioning the justice system.

“I strongly believe that our people would still be in jail trying to get out” if the roles were reversed, Sack said. “The double standard is unreal. I don’t even like using the word Canadian anymore. It’s just so bad.”

Sack said he hoped the UN would hold Canada accountable but wasn’t surprised to see pushback from Ottawa. Defiant, he said the community will never surrender its treaty rights to an assimilationist regime.

“We will fish. We have no other choice,” he said. “We have a community in poverty and we’re just looking for a way out.”

And while Canada’s draft response to the UN is completed and sitting on a desk somewhere, government censors won’t disclose it through the access to information system.

That response will never be made public, according to the information note that was released, which is dated Aug. 10, 2021 and addressed to then-Heritage minister Steven Guilbeault.

Francis said that’s fairly normal depending on the procedures of a given UN body. But she thinks the feds should publish their answer anyway in the spirit of transparency.

“If they had nothing to hide, if they did everything right to protect the Mi’kmaq, and if there’s no substance to these allegations, then why not share the response?”

Heritage Canada referred N2N to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) when first contacted for comment. DFO then referred N2N back to Heritage.

N2N asked Heritage whether the information note remains accurate, which the department confirmed after this article was posted.

Watch both interviews above, or access the documents below.

*Editor’s note: A previous version of this story said Canada’s response was going to be submitted in July 2022. It has been updated to clarify when Ottawa intends to submit it.