Ministers Patty Hajdu, Marc Miller and David Lametti at an Oct. 29 announcing the renewed talks. Photo: APTN

Despite pledging “to sit down immediately and work towards reaching a global resolution,” talks about ending First Nations child welfare litigation have already been underway for 14 months, Federal Court filings show.

A year ago, lawyers for the plaintiffs filed documents asking the court to appoint retired judge Leonard Mandamin as a mediator to help settle the 14-year-old Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) complaint, related appeals and a national class-action lawsuit against the federal government.

Mandamin, who is Anishinaabe from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, has been mediating since early September 2020 “with a view to exploring a global resolution of a significant portion of the proposed class action and the CHRT matter,” counsel explained in the Nov. 2, 2020 filings.

After the court granted the request on May 31, 2021, the talks proceeded quietly behind closed doors, but failed to produce the desired results.

Fast forward to Oct. 29, 2021, a month after losing a major judicial review in Federal Court, when the Liberals challenged that decision but set a deadline of December 2021 for “dropping the appeal upon reaching a global resolution.”

This had the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), who initiated the litigation at the tribunal in 2007, expressing some cautious optimism.

AFN National Chief RoseAnne Archibald said she was “disappointed” by the appeal but “encouraged” by the deadline. The caring society called it an “important opportunity” but added the organization remains ready to “vigorously defend” its position in court if a settlement isn’t reached by January 2022.

Here’s a deeper look at what needs to be hashed out if five more weeks of “focused and intense” negotiations are going to resolve 14 years of litigation.

How far back will victims be compensated?

In 2007, the two organizations went to the human rights commission alleging that Canada discriminated against First Nations kids on reserves and in the Yukon by knowingly underfunding child welfare and refusing to implement Jordan’s Principle.

The tribunal substantiated the complaint in 2016. It awarded $40,000, the maximum allowable amount, to victims of discrimination in 2019.

The compensation order goes back to 2006. But the main discriminatory policy was created in 1991. Known as Directive 20-1, the national policy established modern First Nations child welfare agencies along with the racially discriminatory funding formula.

“The Crown designed its funding channels, including Directive 20-1, based on assumptions ill-suited to the Crown’s stated objectives and without regard to the realities of First Nations communities,” class counsel explained in the filings. “The approach directly and foreseeably resulted in systemic shortcomings ultimately assuring the chronic under-provision of essential services.”

This $6-billion class action was filed in 2019 by lead plaintiff Xavier Moushoom, an Algonquin man taken into foster care when young. Jeremy Meawasige then joined to represent people denied essential services Ottawa was obligated to provide through Jordan’s Principle.

The AFN filed a nearly identical $10-billion claim a year later. The lawsuits combined and now operate together. The Liberal government agreed not to fight certification, but an actual certifying order hasn’t been issued.

The suit proposes to represent victims back to 1991. Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller acknowledged last week that the “people that wouldn’t necessarily be covered by the CHRT order” still need to be paid.

“There are parties that would not be compensated fairly if we were simply to implement the orders in the way that they have been issued,” said Miller. “There would be significant issues with other classes.”

Who gets compensated?

The class action also includes proposed plaintiffs the government said it doesn’t want to pay, and believes it can beat in court.

People who were denied essential services that should’ve been available via Jordan’s Principle between 1991 and now are included in the proposed class. But Canada argued it’s only liable for Jordan’s Principle claims arising after 2007, when the House of Commons adopted the principle.

Class counsel counter-argued that Jordan’s Principle only gave a name to a legal obligation that always existed. But the dispute hampered prior talks.

It became public when lawyers separated the newly joined lawsuit back into two separate lawsuits in response to Canada’s position. While the bulk of the claim would be negotiated, the people Canada wants to fight would head to court.

Read more:

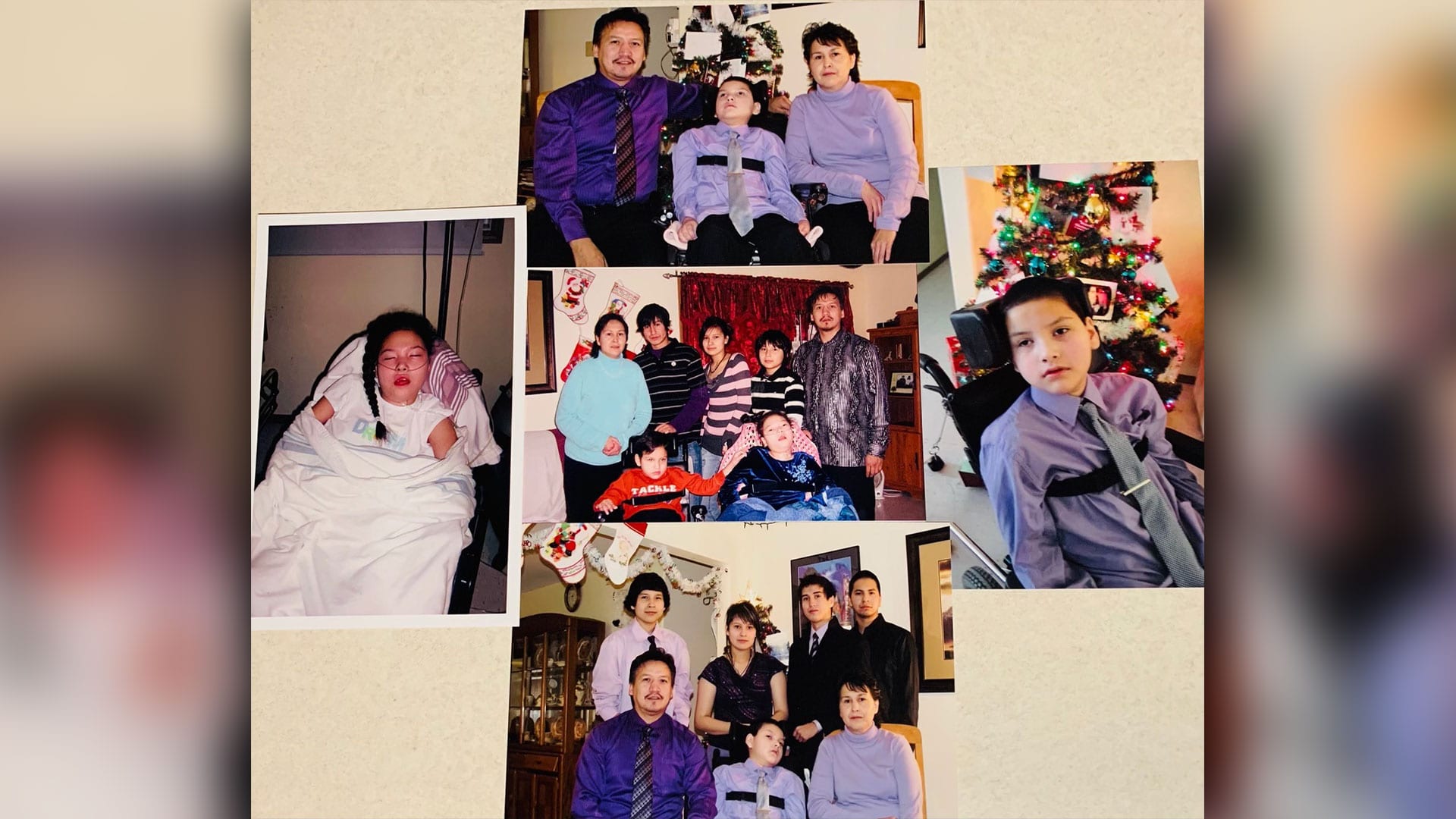

Zach Trout watched two of his children die, now he’s fighting Canada for justice

This latter group is represented by Zach Trout from Cross Lake First Nation in northern Manitoba.

Two of his kids, Sanaye and Jacob Trout, died before age 10 from Batten disease, a rare neurological disorder that normally begins in early childhood and results in seizures, vision loss, deterioration of motor skills, cognitive impairment and eventually death.

Both children, according to the father’s statement of claim, were denied health care solely because they were First Nations kids living on reserve.

Trout told APTN News “there was no resources available for us as Indigenous people. Everything that we had, we had to fight for tooth and nail.”

It’s unclear whether Trout’s claim will be included in a global resolution or litigated separately.

How much will they get, and what will the package look like?

Meanwhile, the caring society said it won’t budge on the $40,000 compensation order approved by the court earlier this year.

Compensation for human rights violations is not the same as damages in civil litigation, its lawyers explained during the judicial review.

“Every victim is entitled to what the tribunal has ordered and what the Federal Court has upheld,” the society said in a statement issued Friday.

Miller was asked several times whether each victim will receive $40,000. His answer indicated Ottawa believes some victims deserve more. But he wouldn’t say how much cash the government thinks people like Jeremy Meawasige and Zach Trout should get.

“There is no intention to reduce the amounts to be paid to the children that have been removed from their families,” Miller told reporters.

There is also uncertainty about how many people would qualify.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) said in February it would cost between $2.2 billion to $4.2 billion to compensate more than 50,000 people based on a strict reading of the tribunal orders.

But 250,000 people could be eligible for compensation tallying $15 billion based on a plan to disburse payment the parties submitted to the tribunal, the PBO added.

The Canadian government has already settled three class actions launched over its racist and assimilationist Indigenous child removal policies: residential schools, the ’60s Scoop and day schools.

The parties indicated they will be tight-lipped over the next month about what the child welfare settlement package will look like in comparison with these other settlements.

“We have put forward a significant financial package to fix the harm caused to First Nations children,” Miller said. “We have also put a significant financial package on the table to address long-term reform.”

While the minister provided few details, he did admit it will cost billions.