Georjann Morriseau walks along High Street Park and looks over the city of Thunder Bay.

It’s a chilly spring day.

“I love our community. I love our people. I love Thunder Bay,” says Morrisseau.

“Despite the challenges, I love Thunder Bay.”

And there’s certainly been challenges.

Especially on the Thunder Bay Police Services Board of which Morriseau is a member.

“I did not go into it thinking that we were going to solve the world’s problems. I didn’t think that things were going to change overnight. I just went in there ready and willing to roll up my sleeves and do my part as both a First Nation person, woman, but also just as a citizen and a regional member of this community,” she says.

Morriseau is Anishnaabe.

A former chief of Fort William First Nation.

In 2019, she was appointed to the police services board, which oversees the city’s police force – one plagued with all sorts of challenges.

It’s a tragic story.

And the Indigenous population is caught in the chaos that is the Thunder Bay police.

Suspicious deaths.

Report after report drawing the same conclusion.

Systemic racism.

Discrimination.

It’s business as usual in Thunder Bay.

And even Morriseau couldn’t change that.

“I really felt that I could bring a renewed perspective to that conversation, and hoped to change the narrative by focusing on these reports and recommendations through education and an awareness that’s more proactive,” she says.

And at first there was a flicker of hope.

It looked like it might work.

Less then a year after her appointment, she was named chair of the board.

A First Nations woman at the head of the table.

But the table was already set.

And she couldn’t really move any of the plates.

“I started to see things that I was quite frankly not comfortable with. You know, and of course my approach is to ask questions and continue to ask questions you know, operate through deductive reasoning. Trying to really figure things out, give everybody the benefit of the doubt,” she says.

“But, I would say, it was fairly quick that it became apparent that there was a leadership issue. That a lot of these issues stem from the leadership, both at the board level and at the service level, at the highest.”

Soon all hell would break loose again as Morriseau filed a human rights complaint against the board and police chief, Sylvie Hauth.

Soon the police board was also put under investigation.

Then the police service itself.

Does this sound familiar?

It’s because we’ve heard this all before.

When APTN Investigates traveled to Thunder Bay in 2017 the force was under a systemic review by the provincial police watchdog over its treatment of Indigenous people and racism within the ranks.

The board was also under investigation.

As was the former police chief.

So was the former mayor.

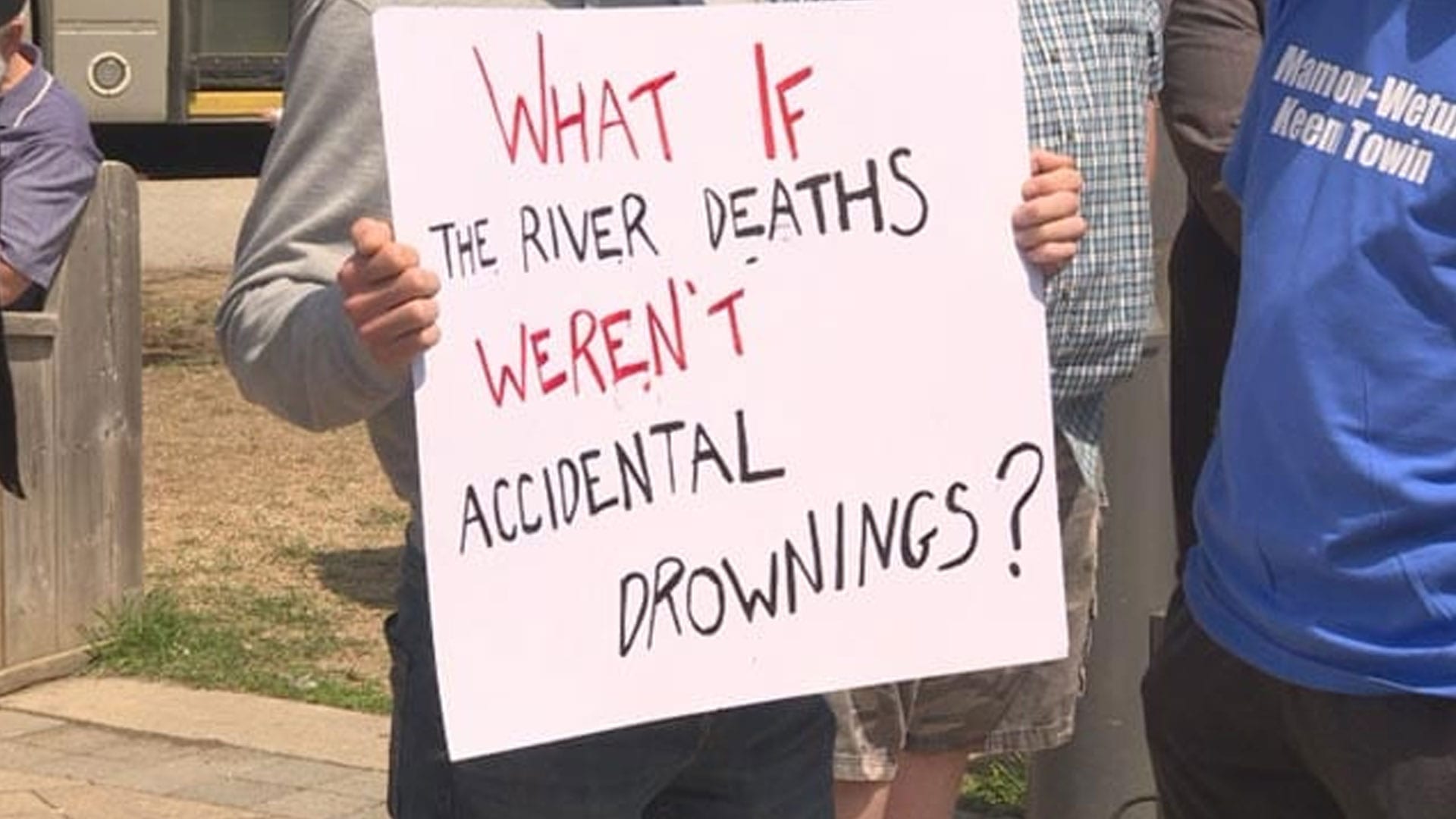

First Nation youth were being pulled from rivers.

So were adults.

It was complete chaos.

Here’s what then acting police chief Sylvie Hauth had to say at a media conference in response.

“To say that we are in challenging times would be an understatement. I would like to assure everyone that the men and women of the Thunder Bay Police Service are doing their duty to serve and protect everyone who visits Thunder Bay or calls Thunder Bay home,” Hauth said.

While she was will willing to admit mistakes were made, she stopped short of calling the situation what it was — a crisis.

She wasn’t alone.

The then police board chair Jackie Dojack was offended when asked that question:

“You know I think that’s kind of an unfair, what would be a crisis? … I mean one can envision all kinds of things that would be a crisis. I think acting chief Hauth was saying, we do not feel that this is a crisis. We said, and her opening remarks were saying that, that we are in challenging times would be an understatement, ok? So we recognize we certainly are in challenging times, that’s different from being in crisis,” Dojack said.

APTN cameras were there and so was reporter Kenneth Jackson.

“Crisis?” said Jackson.

“You have multiple investigations. Your chief’s under investigation, he’s been charged with a crime. Your board’s under investigation. You have multiple kids dying in the river, you don’t know how some of them died, it’s undetermined. That’s not a crisis? I think anywhere else in the world, that’s a crisis.”

Then Hauth said the words that will follow her forever.

“For us currently though, what we see is business as usual.”

Business as usual.

Comments like that have contributed to the public’s general mistrust of the police.

And when you look at the headlines it’s easy to see why.

The police can’t seem to run a proper criminal investigation, at least not when it comes to the sudden deaths of Indigenous people.

It’s resulted in at least eight separate external investigations.

Dozens of sudden deaths investigations having to be re-conducted — sometimes years later when the evidence has vanished, much like any sort of justice loved ones may have had hoped for.

For those outside of the police force there’s been a consistent call that rings as loud today as it ever has: Disband the Thunder Bay police department, or at the very least completely remove those at the helm.

“Systemic racism exists within the Thunder Bay Police Service and needs to be ripped out at its roots,” said Grand Council Chief Reg Niganobe of Anishinabek Nation on March 30, 2022.

“We demand that the Solicitor General of Ontario proceed with dismantling the Thunder Bay Police Service. The Ontario government needs to prioritize listening to the Indigenous peoples who live, work, and visit Thunder Bay.”

Both Niganobe and Anna Betty Achneepineskum, deputy grand chief of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, traveled to Toronto hoping to pressure the province to act.

“The documented racism and willful blindness by the Thunder Bay Police Services and the board have convinced us that, no Indigenous family faced with a tragic death of their loved one, can trust the work of the police services. Today, we stand united … to address the racism and the ongoing victimization of Indigenous families and we want that to end,” Achneepineskum said.

There are few places that know of this type victimization more than at Fort Williams First Nation right next to Thunder Bay.

That’s where we met Travis Boissoneau, the regional deputy grand council chief for Anishinabek Nation.

The union advocates on behalf of 39 member First Nations across the province.

“They’ve had the chance. This is not new, the issue around investigation, the issue around major crime investigations has been around since, well publicly since 1993,” says Boissoneau.

“There have been calls for change since back then. And now with the broken trust, the work continues. The ability for the public to hold the police service and the police board accountability has been ongoing for years and they’ve had the opportunity and there’s been no real change.”

And that seems to be at the root of the problem.

How do you effect meaningful and lasting change within an organization where systemic issues are so entrenched?

Don’t look to Thunder Bay city council he says.

“The elected leadership in Thunder Bay continues to be silent. We live in their wards, we live in their sections, we vote them in and they continue to brush off what are estimated to be 30 per cent of the population, here in Thunder Bay,” says Boissoneau.

“The city council is silent. No one’s condemning what’s going on and no one’s supporting what’s going on. They just sit in silence, they sit in the grey area and as elected leadership they have responsibility to hold all institutions accountable. They have a responsibility to make sure that there’s public safety, exceptional public safety here within the city of Thunder Bay for all citizens.”

Boissoneau adds another point that seems so simple.

“The ignorance within the service that chooses not to do the investigations with exceptional skill and compassion. We have families who have to go home not receiving justice. And, you know, I ask all citizens of Thunder Bay, if this is your family, you would want justice?”

Even people like Morrisseau, who isn’t shy to tell it like it is, couldn’t change it.

Especially when the table turns on you, much like it did on her.

And that began in a HomeSense retail store on a late summer day in 2020.

Morrisseau was approached by a man claiming to be a Thunder Bay police officer who had information about a fellow cop giving information to a local man who operated a social media page about court and police.

The officer told Morrisseau the man texted his work cellphone looking for more “good intel.”

But the text was meant for the officer who previously used the cellphone.

Morrisseau reported the incident to the police board, which sparked a police investigation.

But, she says, the police investigation wasn’t into the nature of the text message but finding out what cop approached her in the store.

It just snowballed leading to her human rights complaint and the Ontario government calling in the Ontario Civilian Police Commission to investigate the police board.

The OPP were also brought in to investigate the police service, including the chief of police.

In total there are 10 human rights complaints and eight reprisal complaints against the police service from active and retired Thunder Bay police officers, as well as civilians.

Each claiming various levels of harassment and discrimination based on mental health, race and gender.

In Thunder Bay, some would say, that’s business as usual.