Birth alerts follow you ‘for the rest of your life’ says Indigenous mom who had newborn taken

Eight years after her son was apprehended at a Calgary hospital, this mom says she lives with severe anxiety, nightmares, intense flashbacks and questions about why her family was separated instead of supported.

Since fighting to get her son out of care in 2013, Cora’s had two more children. All three kids are in her care. Pictured here with her baby girl on Aug. 13, 2021. Photo: Brielle Morgan/IndigiNews

This story is part of a series about birth alerts. It contains content that may be triggering about child apprehension, rape, incest and physical violence and includes images of government documents describing sexual assaults. Please read with care.

Snow fell through the darkness as Cora gave birth to Connor in the middle of the night at Rockyview General Hospital in Calgary.

Four days later, a social worker from Alberta’s Ministry of Children’s Services (MCS) came to the hospital and served her with an apprehension order. They were taking her son into government care.

That was January 2013. Looking back, Cora believes she was subjected to a birth alert, and she wants people to understand how deeply haunted she is, eight years later, by this experience.

“It follows you for the rest of your life … I still, to this day, deal with severe anxiety,” says Cora, whose real name IndigiNews is withholding to protect her privacy and that of her children.

A “birth alert” is when a social worker flags an expectant parent to hospital staff — without the parent’s consent — because they believe the unborn baby’s at risk. Hospital staff are then expected to let a social worker know once the baby’s born.

It’s a practice that can result in a child being taken from their parent(s), and does “approximately 28% of the time” — at least in British Columbia, according to government records published by IndigiNews in January.

It’s a practice the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls called “racist and discriminatory and … a gross violation of the rights of the child, the mother, and the community,” in its final report in 2019.

And it’s a practice that disproportionately impacts Indigenous women, in keeping with Canada’s history of colonial, racist policies.

In B.C., for example, records obtained by IndigiNews show there were at least 444 birth alerts issued between January 2018 and September 2019, and in 2018, 58 per cent of birth alerts targeted Indigenous parents — despite the fact that Indigenous Peoples make up just six per cent of B.C.’s population, according to the 2016 census.

In Alberta, an MCS spokesperson couldn’t say how many birth alerts issued before the fall of 2019 — when the province “formally abandoned” the practice — targeted Indigenous families. “That information was not tracked,” they said in an email to IndigiNews.

But they did say there were 18 birth alerts issued “in the years prior” to 2019.

Alberta is one of many provinces to have (at least formally) abandoned the practice of issuing birth alerts in recent years. But Cora, who’s Cree Métis, wants people to understand that she continues to be impacted by the sudden and unexpected removal of her newborn.

Certain triggers can cause “intense flashbacks,” she says.

“You could be at work and the phone rings and you just jump and you’re terrified. It could be something as simple as walking past a courthouse or walking past any type of child and family services office.”

Giving birth isn’t the same afterwards, says Cora, who had another baby this summer in Victoria, B.C.

“I couldn’t wait to get out of the hospital. I was like, ‘I’m so terrified of being here — What if they call the ministry on me for any little thing? What happens if they try to turn my race against me again? What happens if I change a diaper wrong?’ All it takes is one phone call.”

Cora says she decided to come forward after reading a story published by IndigiNews in January — which revealed that months before B.C. officially stopped issuing birth alerts, government lawyers advised the Ministry of Children and Family Development that the practice was “illegal and unconstitutional.”

Indigenous leaders and B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth have since called on the province to publicly apologize, but that’s yet to happen. Meanwhile, earlier this month a proposed class action lawsuit was launched in B.C.’s Supreme Court on behalf of parents subjected to birth alerts. It’s the first step in a “coordinated national litigation effort,” according to one of the firms working on the case.

Cora says she wants other parents who’ve experienced birth alerts to know “they’re not alone.” And she wants them to know there’s hope. While she says it took eight months of fighting through the courts, eventually, she got her son back.

Experiencing a birth alert

Cora was 19 when she had Connor (whose real name IndigiNews is also withholding).

“I was 34 weeks and six days when I had my son,” she says. “He came out and the cord was wrapped around his neck, and five minutes after birth, his heart had stopped.”

Connor was sent to the newborn intensive care unit (NICU).

Two days later, on Jan. 21, Cora was still recovering at the hospital when a woman came into her room and introduced herself as a child and family services worker.

“They said they wanted to do an investigation, and they said it was due to an emergency because someone was concerned,” says Cora.

“I started to have an anxiety attack. My heart felt like it was pounding really fast, and you get that lump in your throat, and you’re like, just breathe. It’s okay. Everything will be fine if you tell them the truth — then they won’t take your kid away.”

Cora recalls telling the caseworker about the strained relationships she had with her own parents. She’d never been in government care, but as a teenager she’d sought support from the ministry.

“I begged them to take me out of my home when I was 17,” Cora tells IndigiNews. “I was dealing with an abusive situation with my biological dad, and the abuse was getting worse, and they refused to take me out of my home, so I got myself out.”

Cora recalls asking the caseworker in her hospital room for help.

“I was like, can you guys please give me this support? I would like some in-home support, and I’d like referrals for counseling,” she says. “They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, we’ll totally do that. We’ll hook you up with all the resources that you need. It’s not a problem.’”

Cora was discharged from the hospital late the next evening.

“I was still in a lot of pain because of the episiotomy,” she says. “It was really hard because I had to leave my son in the hospital, and I didn’t want to leave him behind.”

The next day, on Jan. 23, she recalls using public transit to return to the hospital, and getting lost because she “had only been there through cab rides.”

“I finally got to the hospital about five o’clock, and I wanted to breastfeed my son. [The nurse] told me, ‘No, he just ate. You can pump’ … “Every time I asked for help with breastfeeding, they told me he just ate.”

She was sitting next to her son’s bed in the NICU when the caseworker returned, she says.

“She’s like, ‘Hi, just let me know when you’re done pumping and we’re just gonna have a talk in a private room.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, is everything okay?’ She’s like, ‘Yeah, everything’s fine.’”

Cora finished pumping and met up with the caseworker.

“She told me that she was apprehending my son and that I was an unfit mom,” she says.

“I asked her, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and she told me I did nothing wrong … She said that they’ll make sure that I get the counselling and the supports that I need. [She said] it’s just not safe for [Connor] to be with me. And I’m like, how could I do ‘nothing wrong’ if you’re taking my son away?”

She recalls the caseworker leaving to call Connor’s father — whom we’ll call Dave — and returning to find her in tears.

“She told me I had to calm down because they didn’t want the other moms in the NICU to see [me] hysterically crying,” she says. “Then she told me that I was going to be escorted off the property by security.

“I still have nightmares about it. I remember the security guards walking me and leading me by the arm out of the hospital and off the property … I was crying so badly that I couldn’t see out of my glasses. When I got off the elevator they told me I was going the wrong way,” she says, adding that she wasn’t allowed to say goodbye to Connor.

“I could barely breathe because it was just so painful … And it just felt like I had everything taken away, and I had lost everything in my life.”

Cora says she felt completely blindsided by the apprehension.

“Why is it I didn’t get a warning?” she asks in retrospect. “I just lost my son.”

IndigiNews reviewed records obtained by Cora’s lawyer — court documents and ministry paperwork — and couldn’t find any notes to indicate that Cora’s caseworker offered her any supports or considered any less intrusive options before removing her baby.

On Sept. 13, IndigiNews asked Rebecca Schulz, Alberta’s minister of children’s services (MCS) for an interview to explain, among other things, where to look in a parent’s file for evidence that a caseworker explored other options before apprehending a baby.

IndigiNews was told the minister was “unavailable for an interview.”

On Sept. 15, an MCS spokesperson sent an email — which doesn’t answer the question posed.

“All concerns that are reported to Child Intervention regarding a child’s safety and wellbeing are assessed to determine if a child is in need of intervention as defined under the Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act … All decisions made about a child and family, including the decision to bring a child into government care, are guided by this legislation,” they wrote.

“When a child is brought into government care, it is the last resort and done for the safety and protection of that child.”

The pain of forced separation

Asked what it’s like to be forcibly separated from your baby for eight months, Cora is to the point. “It was hell,” she says.

“It was watching other moms push their babies around in strollers and carrying them on their chest, and being like … why can’t I have that with my son?”

Cora had limited access to Connor via supervised visits a few times a week.

At the end of their allotted two hours, she says “he would do this painful cry that is just gut-wrenching.”

When Connor had to go to the hospital for breathing issues, she says she wasn’t allowed to be there to support him. “That’s something you’re supposed to be able to do as a parent. And I couldn’t do it … The caseworker never even called me.”

Cora says she kept herself busy by going out with friends and teaching herself how to knit. She says she was constantly sending “goodies” to the foster home through the drivers that would take her son to and from supervised visits.

“I sent my birthday cake because I wanted to share it with the kids … I was constantly sending clothes … diapers and wipes … I wanted to feel like I had contributed to my son,” she explains. “The first teddy bear I got him — he still has it to this day.”

Cora says it took eight months to get Connor back, and it involved finding a lawyer, taking parenting classes, undergoing a parenting assessment and meeting with her assigned caseworker on a regular basis. As for the counselling she’d asked the caseworker to help her access, she says she ended up finding and paying for it herself.

“They never set any of that up,” she says. “I was like, okay, whatever, I just can’t care. I just want to get my son back. That’s the main goal here.”

She says she worried about Connor’s well-being “all the time.” And she didn’t get to meet his foster parent until after she got him back.

“I would wake up sometimes in the middle of the night, thinking that I heard a baby crying, running to the bassinet … This just happened again, during my last pregnancy — I’d wake up, look in the bassinet, and it’s like instant flashback. It doesn’t go away, and it’s been eight years.”

‘The damage is very extensive’

The kind of trauma inflicted by a birth alert isn’t “just a moment in time,” says Jeannine Carriere, a professor at the University of Victoria’s School of Social Work. “It’s lifelong and causes undue health impacts for the woman and also for her children.”

Carriere says she spent more than a decade working with Indigenous families through various frontline and administrative positions — including a two-year stint as Alberta’s associate director for Aboriginal child welfare in the ‘90s — before turning to academia. She says she’s often called upon to act as an expert witness in child-welfare trials.

“I feel like I’ve done the whole gamut from changing diapers and helping moms to [working at] a high level in the ministry,” says Carriere.

With Cora’s permission IndigiNews shared her records with Carriere, who says notes in the file suggest Cora was subject to a birth alert.

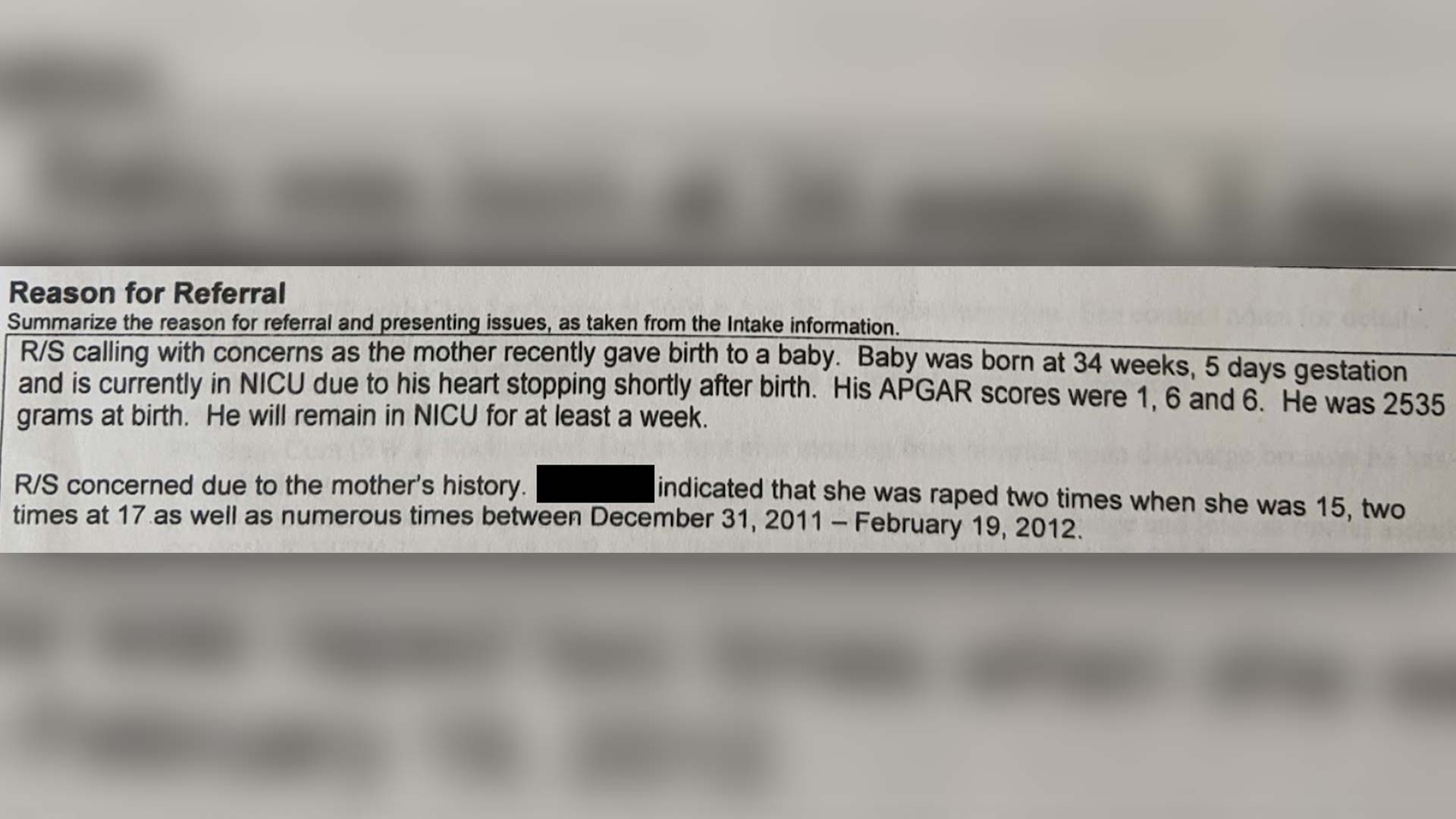

For example, in one document Cora’s caseworker listed reasons why the ministry was getting involved: “R/S calling with concerns as the mother recently gave birth to a baby … R/S concerned due to the mother’s history.”

(R/S is shorthand for “Referral or Reporting Source,” says Carriere, adding that she confirmed this with a social worker in Alberta — where baby Connor was apprehended.)

According to an MCS spokesperson, birth alerts were “formally abandoned” in the fall of 2019 as part of the province’s “ongoing commitment to approach child intervention with an emphasis on keeping families together whenever safely possible.”

“Any Albertan who wants to know if they were subject to a birth alert has the right to their own information and can make an application under the Freedom of Information and Privacy Act,” they wrote in an email to IndigiNews.

In Carriere’s view, “being scrutinized with a birth alert and the subsequent apprehension of your child … causes generational trauma.”

“In my belief system, there is such a thing as blood memory. So when mom is feeling that stress and trauma in her body and baby is still in utero, then the baby is feeling that as well. The damage is very extensive.”

She draws her perspective not only through her work, but also from her personal experience as someone who was adopted at birth “by a French-Canadian family.”

“I’m Métis of Assiniboine, Cree and French on my mother’s side, and Mediterranean ancestry on my father’s side,” she says. “My spirit name in Cree is Sohki Aski Esquao (Strong Earth Woman).

“It’s a personal story for me as well, not only because I’m Métis, but also because of my family’s involvement with child welfare and what my mother went through when I was in utero and she was being convinced that she should relinquish me for adoption.

“I believe there’s been some impacts on me,” she says. “And, of course, the rest of my family as well.”

A close look at Cora’s file reveals ‘extremely poor practice’

Wanting to understand the reasons given for Connor’s apprehension, IndigiNews reviewed documents prepared by ministry workers and the Provincial Court of Alberta.

On Jan. 21, 2013, when the caseworker first showed up at the hospital and interviewed Cora, she took notes about her relationship with Dave: “[Cora] describes she and [Dave’s] relationship as safe and supportive,” she wrote.

About their financial situation, she wrote: Dave “works as a truck driver.” About their health: Cora “struggled with depression in high school, and has struggled with anorexia … [Dave] was diagnosed with depression when his wife left him. No longer a concern.” About their drug and alcohol usage: Cora “reported a few sips of vodka during her pregnancy and no drugs … [Dave] does not use drugs … needs to have beer and play video games when he is stressed.”

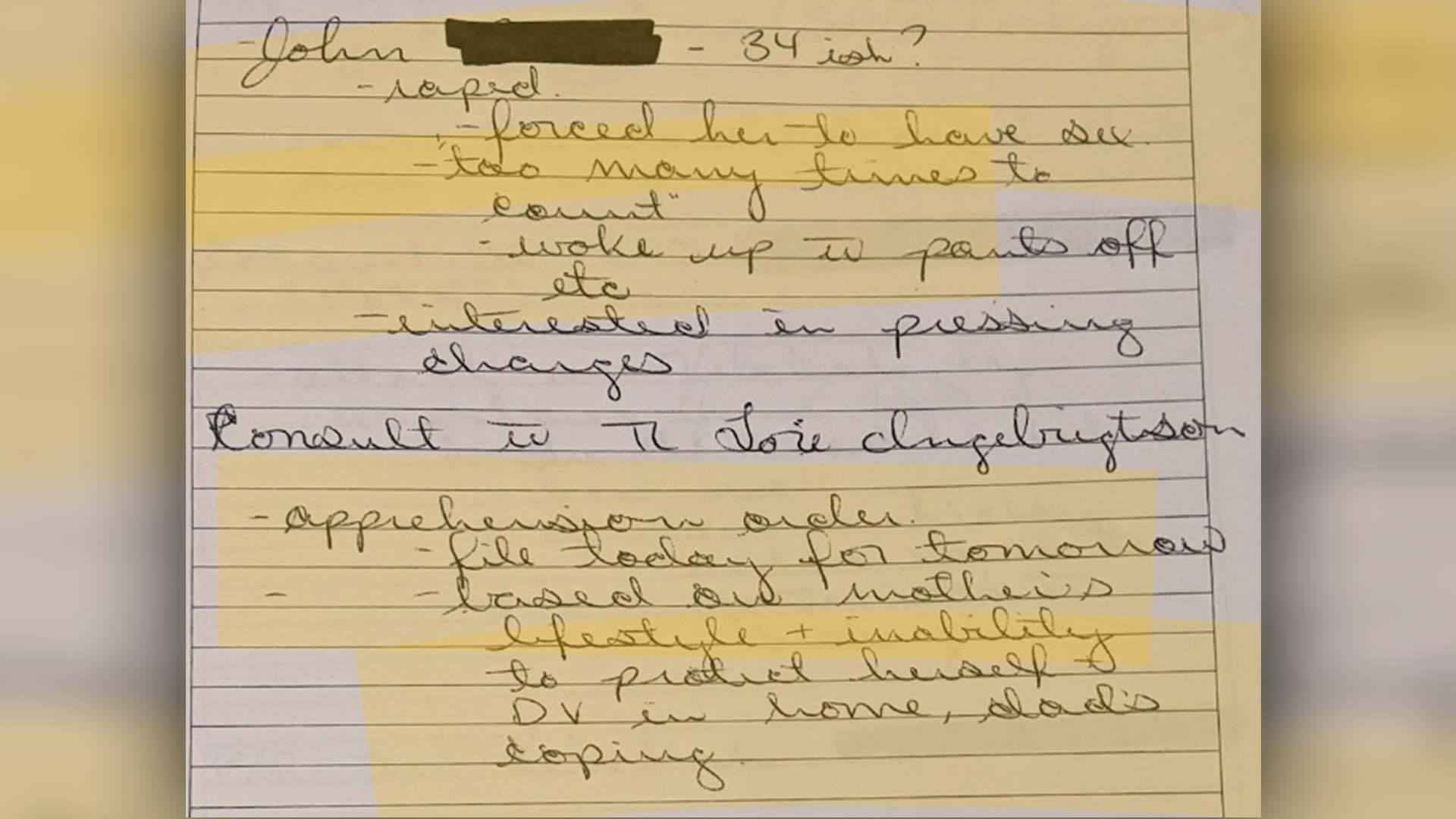

She also took notes about sexual assaults Cora said she experienced: “[Cora] described several sexual assaults that have happened to her since she was 15, including her step father, neighbours, strangers and a man named John who raped her several times between December 31, 2011 and February 19, 2012 at her mother’s home.”

Immediately after this, she wrote: “[Cora] was not residing at her mother’s home at this time, however, continued to return to her mother’s home despite these occurrences.”

IndigiNews asked Carriere what she makes of the notes about the sexual assaults.

“That sounds very judgmental to me and extremely poor practice,” she says. “What are they inferring by saying that she kept returning? Are they inferring that she wanted these sexual encounters?”

Carriere says caseworkers’ notes can “definitely” reveal prejudice and racism.

“We encourage workers to be very cautious of bias in their notes, because it’s always possible that their notes are going to end up in court,” she says.

“But the bias, I think, seeps in — especially after a while, when workers become a little more seasoned and maybe a little more burned out or frustrated or the caseloads are getting higher … They’re not as cautious. And the bias becomes more obvious.”

Cora says “it really hurts” to see these notes in her file. “It’s like here I am asking for help, and instead of helping, you make me feel like I was the one at fault, like I was the one to blame.”

The next day the caseworker took more notes about the sexual assaults, and underneath these notes they wrote: “Apprehension order — file today for tomorrow based on mother’s lifestyle and inability to protect herself — DV in home, dad’s coping.”

She elaborated on her note about the “DV” — shorthand for “domestic violence” — in an “Application for an Apprehension Order” stamped by the Provincial Court of Alberta on Jan. 23, 2013:

“There are concerns regarding the father, [Dave], in regards to his ability to make appropriate choices and coping. [Dave] currently lives with his female cousin with whom he had an incestuous relationship 3 years ago,” it said. “[Cora] and this cousin have had a physically violent relationship in the past including punching, kicking, pulling hair and pushing into walls. [Cora] is planning on returning to this home when discharged from the hospital.”

At the end of the application, the caseworker summed up her concerns: “Due to the concerns in regards to the domestic violence in the home, the parents coping abilities and ability to make appropriate choices, the Director is requesting an Apprehension Order.”

Cora says she remembers telling the caseworker about a physical fight she’d had with Dave’s cousin — a couple years before having Connor — during their initial conversation at the hospital. But she doesn’t recall the worker explaining her concerns about their living situation until after Connor was apprehended, and the case was before the court.

At that point, Cora says she learned Dave’s cousin had “a form of schizophrenia” and wasn’t “legally allowed near minors because she gets too violent.”

IndigiNews asked MCS what kind of support should be offered to a mother when there are concerns about “domestic violence in the home.”

In an emailed reply, a ministry spokesperson wrote that in such cases a mother could be referred to “supports such [as] Family Violence Information Line, or women’s emergency shelter, or in cases where there is immediate danger, local law enforcement authorities.”

But Cora says she wasn’t offered any of these supports.

“Instead of telling me [about their concerns with my living arrangements] in the hospital so I could go to a woman’s shelter, they just decided to take him away … I’m like, you didn’t even give me a chance.”

Carriere figures if the ministry had concerns about Dave’s cousin’s state of mind, they may not have shared them with Cora “because of confidentiality.”

“But yet it’s used as a rationale to take her baby,” she says. “It’s so bizarre.”

Resources ‘keep going to the wrong people’

Cora’s experience with the child-welfare system wasn’t entirely negative. There were some bright spots.

While she describes her first caseworker as “just toxic,” the second caseworker assigned to her file was “a lot better,” she says. “She made me feel like I was human.”

“The first time I met her, she was like, ‘Hi. My name is [_____], and I’d like to give you your son back … I’ve seen everything that you’ve been doing. You’re like the poster parent for people who go through the foster care system. You’ve done everything. We’re so proud of you. Let’s see what we can do.’”

Cora says she started getting more (and longer) visits.

She says her son’s foster mom — whom she finally met after the baby was returned — also “grew to become a support person,” not only for Connor, but for Cora.

“I’m so grateful for her,” she says. “She taught me a few things, like … she told me how [Connor] liked to be swaddled because it made him feel like he was back in the womb.”

This is the kind of support struggling parents need, Cora says.

“I think that’s what we need to start setting up in the system — more support people who just show up and are like, ‘Hey, I’m here to help you. What can I do for you? Oh, you need me to wash some dishes for you? … Oh, you need a nap and you want someone to hold the baby? Okay, let me just have some snuggle times.’

“I honestly don’t believe apprehending the child should be their first option,” she says. “They should try to work with the family first, before intervening, which is not what they did in my case.”

Carriere agrees with Cora. Too often, “it’s a battlefield for these families,” she says.

“Yes, we have poverty in our communities. And, yes, moms are struggling and need more supports — I’m not disputing that … [but] the resources keep going to the wrong people,” Carriere says.

“The foster care system or the temporary care system for that baby is the one that benefitted, while mom was … fighting for her baby.”

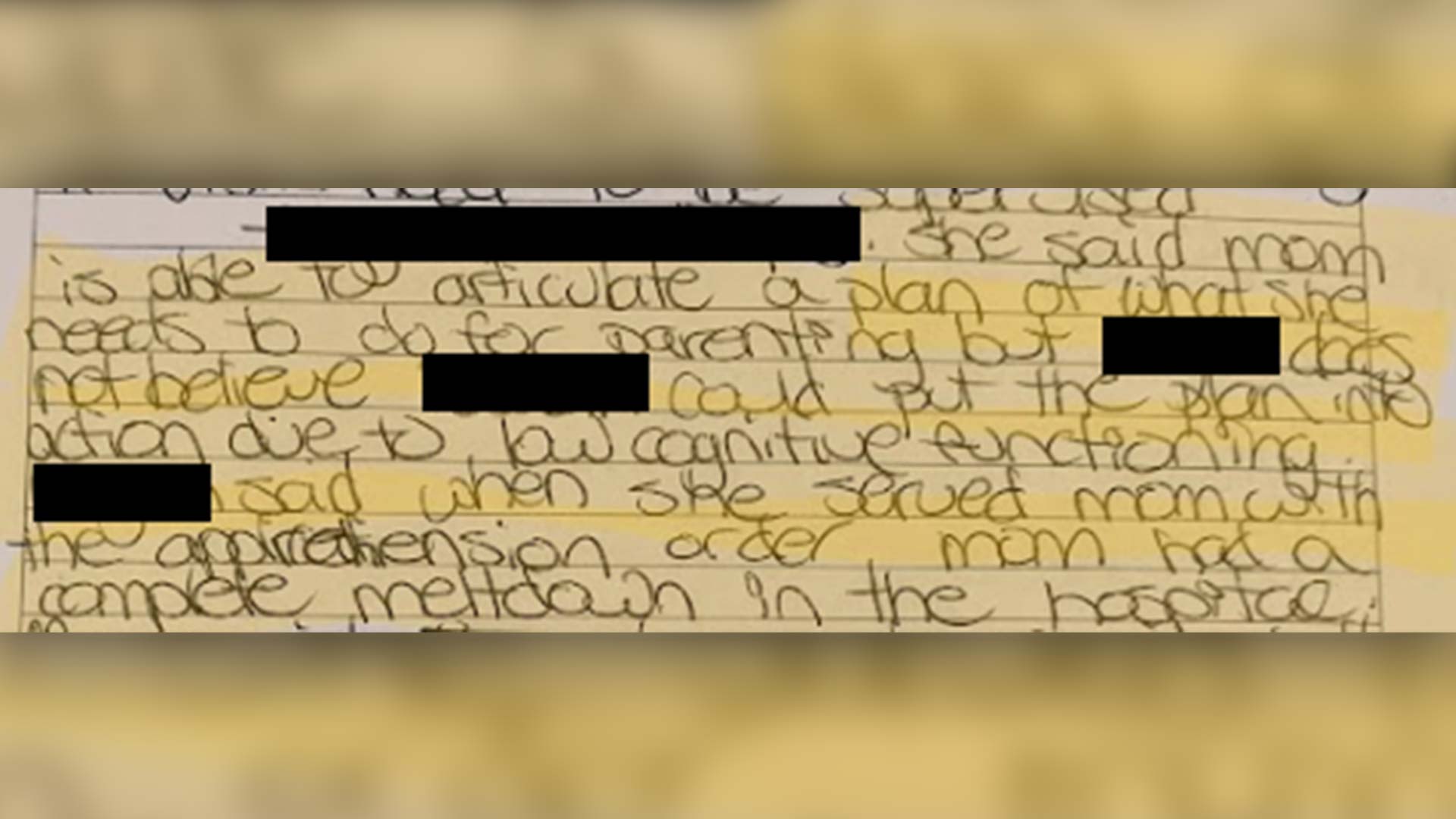

According to notes taken by a caseworker and dated Jan. 24, 2013, while Cora was “able to articulate a plan of what she needs to do for parenting,” the caseworker did “not believe [Cora] could put the plan into action due to low cognitive functioning.” After this, it says: “mom had a complete meltdown in the hospital” when served with the apprehension order.

Elsewhere in the file, it’s noted that Cora’s supposed low cognitive functioning has never been formally diagnosed.

On Jan. 30, 2013, a caseworker took notes about a meeting they had with Cora. She writes that Cora “said she does not understand what the concerns are.” After the caseworker explained her concerns about Dave’s cousin, Cora said they’re willing to ask her “to move out if necessary.”

“[Cora] said she is willing to do whatever she needs to,” wrote the caseworker.

IndigiNews asked MCS what kind of support should be offered to a mother when there are concerns about her “lifestyle and inability to protect herself.”

“We emphasize the great need for prevention and early intervention by providing resources like Family Resource Networks which were established in April 2020 to give families supports and services province-wide,” wrote the ministry’s spokesperson.

“If a child needs intervention, [Child Intervention] works with the family, extended family, community partners and any other supports that the family has to help the parents identify what they are doing that helps to keep the child safe and also what parents need to improve upon to keep the child safe.”

Cora knew what she needed, says Carriere, “but the system is not paying attention to her.”

“It drives me crazy that systems like the ministry on one hand will talk about how they support kinship care and, you know, ‘families first’ … and yet on the other hand, we have these moms who can’t get the support they need to keep their children.”

Cora needed “immediate” access to support services. Not services designed to police her, but rather services that are “genuinely interested in helping her parent her baby and give her the break that she needed,” says Carriere.

“Holding the baby while she has a nap — that’s not rocket science, you know? But what a difference that can make.”

‘Looking forward more to the future’

This summer, Cora packed up her three kids and hit the road, bound for Calgary. She says she’s going back to school to become a medical office assistant.

“I’m used to being judged by the medical profession, which is kind of why I’m trying to go into the medical profession — to change that myself, and let people know, like, there’s someone who cares and is here for you,” she says.

“I’m looking forward more to the future right now and learning more about who I am, as someone who is part First Nations, as well as teaching my kids who we are.”

She says she’s planning a road trip with her sister to Banff, where the public library keeps a book written by their grandmother about their family’s history.

As for her relationship with her first-born, Connor — who’s now eight — she says sometimes their relationship feels “very distant because of that bond being disconnected,” but she’s “trying to work with that.”

She describes him as sweet and caring.

“Ever since he’s been able to walk and talk, he’s just so overprotective [of] all girls [and] anyone who’s a baby,” she says. “He’s a nurturer and a little warrior.”