Susie Kuneyuna no longer lives down the street from her family in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, but she also no longer lives in fear of her abuser.

“It feels to be free of him, not be tied down. In the end he had control of me, emotional, physical and mental abuse,” Kuneyuna says.

Today, photographs of relatives young and old line the walls of her apartment in Yellowknife, a cozy space carved out as her own since 2017.

Despite her safe space, Kuneyuna has had frequent reminders throughout the COVID-19 pandemic of the prevalence of violence against women.

They come in form of turbulent situations that arise just beyond her living room.

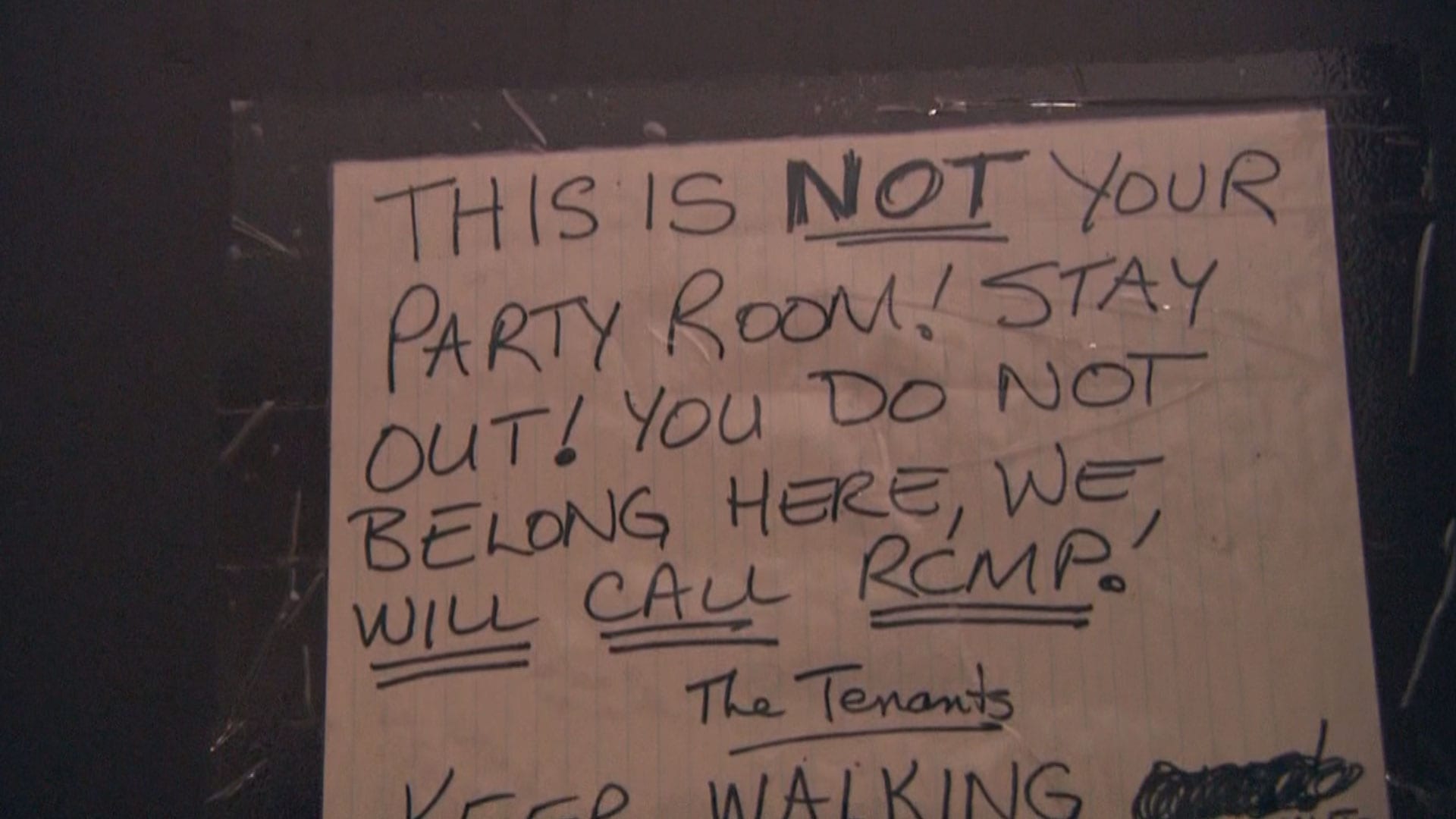

“We aren’t supposed to be doing laundry after 11 p.m. so you can tell when there’s a loud, the garbage gets kicked around and there will be arguing. Many times, there will be a woman screaming for help,” she said.

Kuneyuna routinely calls RCMP to intervene as homeless and vulnerable persons sneak into the downtown apartment cause a ruckus.

It’s triggering, but she’s empathetic for the women, as she herself has experienced barriers in fleeing violence and accessing social supports.

“So many women are between a rock and a hard place because they have nowhere to go. Their family nearby is already overcrowded, where would they put them,” she said.

Kuneyuna recalled one time she fled a violent situation years ago.

“I remember one time I got out and went to my son’s house. I stayed for hours got so worried about my husband that I ended up going back home – only to be abused for running away,” Kuneyuna said.

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical associations and women’s social support organizations have reported higher rates in domestic violence due to self-isolation measures and economic instability.

According to the territorial health department’s report Social Indicators Covid-19 Pandemic, released in December 2020, the N.W.T. handed out more emergency protection orders, a form of restraining order, over the same time frame than previous years.

The report also stated a decline in admissions to family violence shelters in 2020 than in previous years, but cautioned careful interpretation of the data as there may have been confusion around whether shelters were open or not along with uncertainty around the safety of shelter as the public health orders recommended residents to stay in their homes.

“When individuals are under constant surveillance from their abuser, they are less able to reach out for help and to get to safety if need be. The orders also keep people isolated from friends and family meaning that there are fewer opportunities for informal support as well,” as stated in the report.

Shelters were also made to comply with public health orders around physical distancing which resulted in reduced capacity and ultimately affected the overall numbers of women using the space. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical associations and women’s social support organizations have reported higher rates in domestic violence due to self-isolation measures and economic instability.

In the N.W.T., there was already many social and physical challenges for women fleeing violence: remote communities with far distances in-between shelters, lack of housing options, high cost of living, food insecurity and much more.

Dr. Pertice Moffitt of Yellowknife spoke about domestic homicide at hearings of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and is wrapping up her work researching domestic violence in vulnerable populations in Canada.

She interviewed families involved in domestic homicides in Canada in an effort to uncover the unique needs of Indigenous, rural, remote and northern communities and children exposed to this violence.

“We don’t have police in every community. Some of the communities are very small and we don’t have victim services in every community. We don’t have shelters, and we don’t have safe houses – so those right there are huge,” Moffitt said.

One of the main objectives of the project is to assist in the development of a national database on domestic violence homicide.

“A database for domestic homicide was one of the TRC’s (Truth and Reconciliation) calls to action. We will never know if we are improving if we do not have databases to understand the circumstances – and how loved ones are surviving after it,” she said.

Anonymity in remote communities has always been a common concern facing Indigenous women in northern communities, according to Moffitt.

When the only social and health support worker available is a relative to the victim and their family, a relative to a victim is the local go-to for social and health supports, there may be hesitation to access services.

In autumn 2020, the territorial government set up an interdepartmental working group to review programs providing family violence supports.

Moffitt was pleased with this development, but noted immediate action is necessary to help families in the immediate – like implementing screening questions in government facilities such as emergency departments at hospitals and health clinics.

“It could be for every pregnant woman at every visit. Because people could be very reluctant, but if you ask the question every time and people may become more trusting of the healthcare professional,” Moffitt said.

Kuneyuna agreed that health workers could and should assist in intimate partner violence. After all, she herself turned to a doctor for help.

In 2017 when she endured a stroke, Kuneyuna was medevacked from her home of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut to Stanton Territorial Hospital in Yellowknife, N.W.T.

She told APTN News her abuser was permitted to travel with her as a medical escort, despite RCMP having recently responded to a call of that same abuser threatening to kill Kuneyuna.

But the trip to Yellowknife turned out to be a blessing in disguise. On the following day in the hospital when Kuneyuna had rested up and had regained the ability to talk – she told the doctor of her abuser’s past.

Victim services were involved, her abuser dismissed of escort duties and sent back north while Kuneyuna transitioned into a Yellowknife YWCA women’s shelter.

She showed APTN the quilt she made during her first few weeks in Yellowknife a project she completed with other residents as each helped one another get back on their feet.

“This was my healing project; I literally stitched my heart back together with every square. I didn’t want to be a victim any longer. I wanted to be a survivor I want to help women, victims of abuse,” she said.