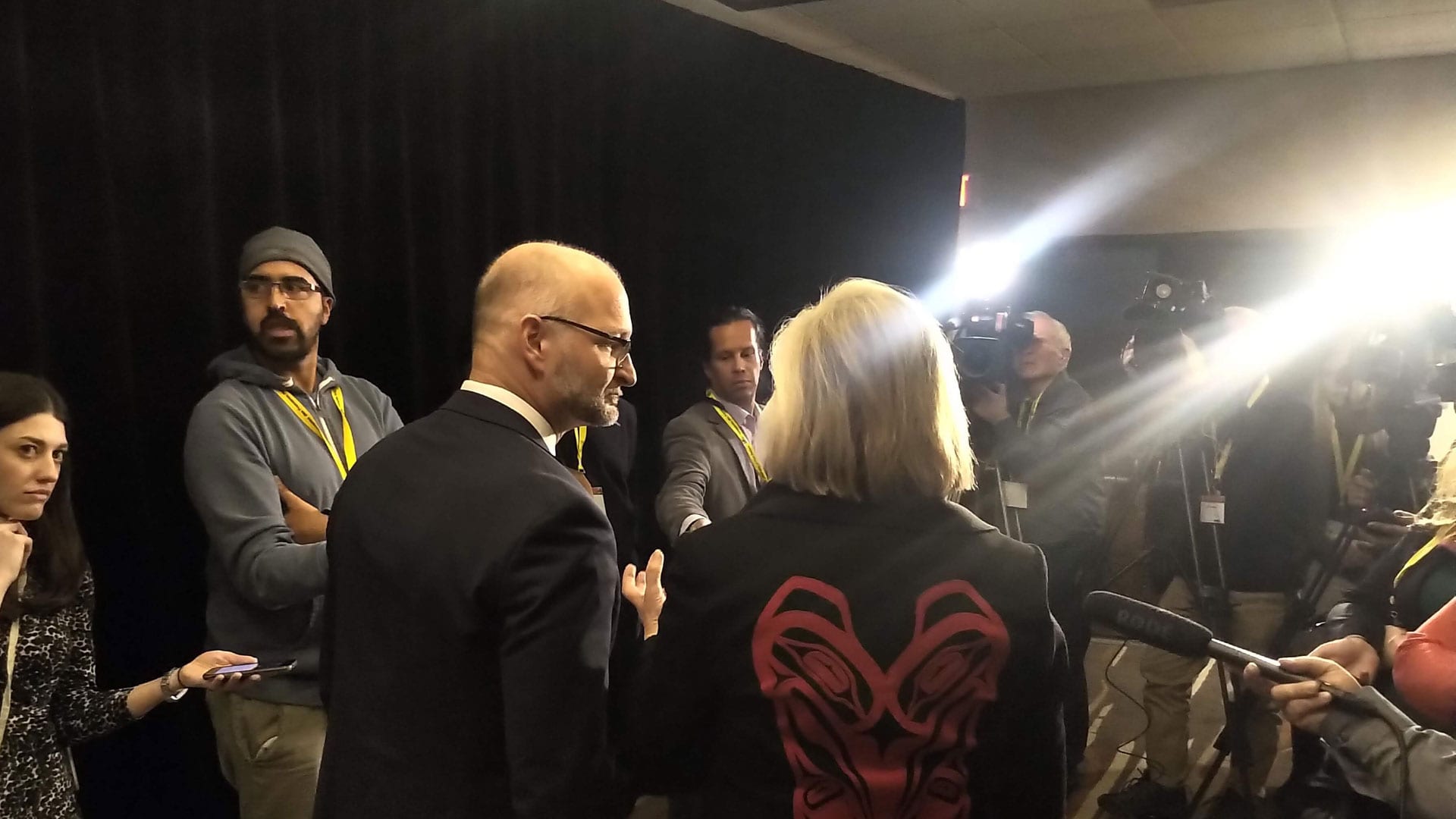

Many say Canada needs UNDRIP so protests like this one, which happened in Ottawa during the Wet'suwet'en pipeline standoff, don't have to happen. But not everyone is convinced C-15 will complete that objective. Photo: APTN

Five years ago, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called on all levels of government to “fully adopt and implement” the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).

Now, with much fanfare, the Liberal government has tabled legislation to do that. On the fifth anniversary of the TRC calls to action, APTN News digs into Ottawa’s proposed UNDRIP act.

Non-Indigenous opponents fear it would give First Nations, Inuit and Metis too much power. Indigenous opponents fear it won’t give them enough. Supporters tout it as a leap forward on rights, title and reconciliation. Detractors say it strengthens the shackles of the colonial status quo.

A battle is brewing over UNDRIP in and outside the halls of power – and a whole lot remains unclear.

“As with any law, there’s unknowns,” said professor and legal scholar John Borrows, reached by phone a day after Justice Minister David Lametti tabled Bill C-15 in the House of Commons.

“There’s unknowns with our Constitution. There’s unknowns with UNDRIP. But the fact that this has got a process to work through those unknowns is better than the free for all we have right now.”

Unknowns notwithstanding, here’s a primer on what we do know: what UNDRIP is, what the proposed law would do and what it could mean for First Nations, Inuit and Metis rights.

But first, the basics: What is UNDRIP?

UNDRIP is a “very important international document,” according to Carleton University scholar Frances Abele. “Canadian Indigenous people were a very important factor in that declaration ultimately being adopted by the UN.”

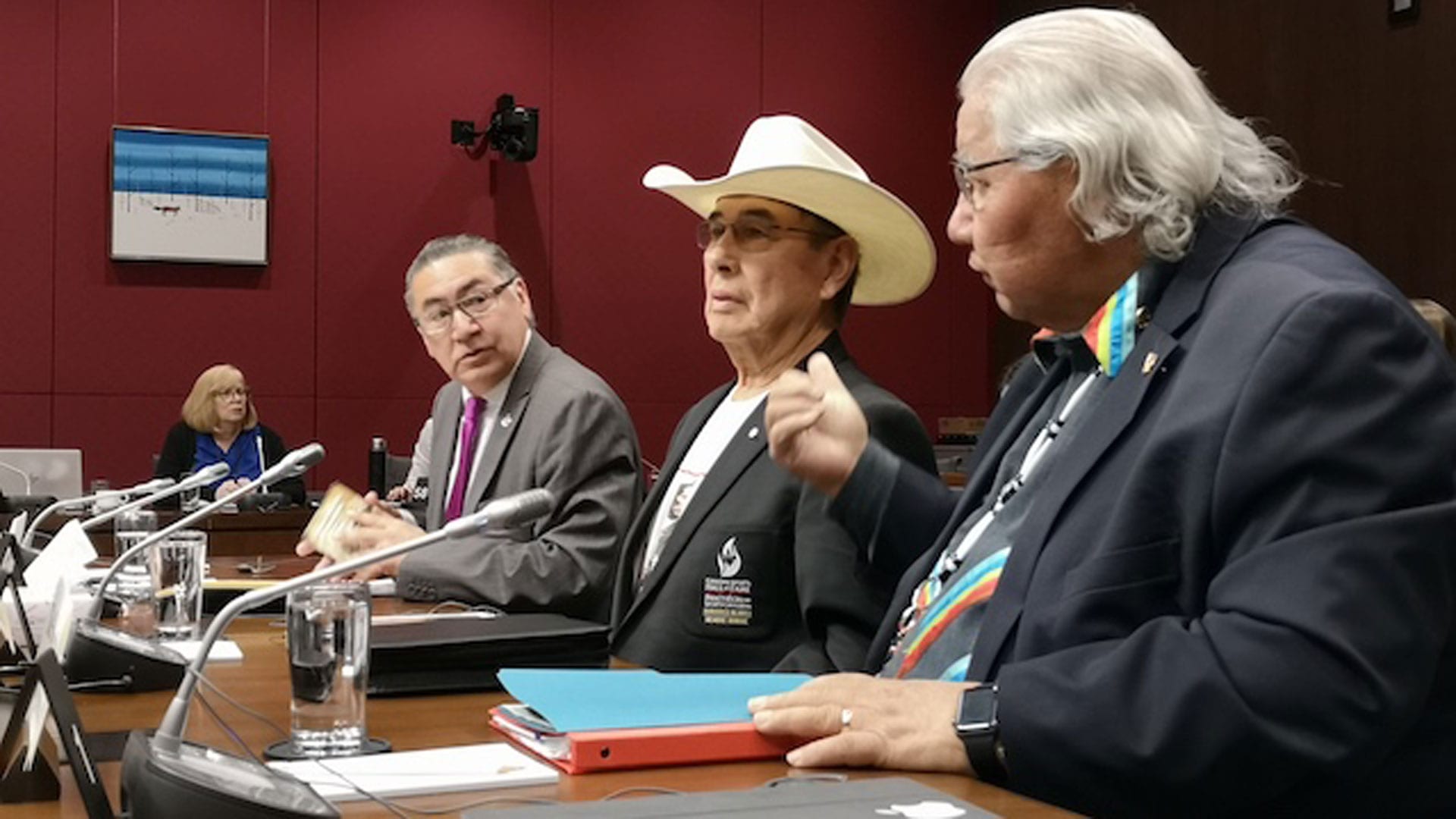

A residential school survivor, former TRC commissioner, grand chief, lawyer and politician, Wilton Littlechild was a big part of that factor.

He describes the declaration like a pipedream that began in 1977 when he was a member of the first-ever Indigenous delegation to the UN.

“It took us eight years to convince the UN we were human beings. Eight years,” he said during the 2020 Assembly of First Nations general assembly.

“As we sit here today, they’re still fighting us from participating at all levels of the United Nations in our own right as sovereign nations. So the battle is still on, and this is really only step one.”

That battle started in 1982. Twenty-five years later, 144 states adopted the finished, polished declaration.

But four with colonial histories of persecuting and dispossessing Indigenous peoples – Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada – did not.

“It was very important when, not so long ago, the Canadian federal government finally, unreservedly, committed to respecting the UN declaration,” said Abele.

That was in 2016 under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The Stephen Harper administration endorsed the declaration as an “aspirational document” in 2010. The other three states have now endorsed it too.

But what does unreservedly endorsing UNDRIP mean?

According to UN materials, it means committing to uphold the 32-page document’s 46 articles, which lay out universal human rights standards tailored to Indigenous peoples across the globe.

Says Article 7, for instance, “Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group to another group.”

A notable final clause for a country still reckoning with the devastating intergenerational impacts of residential schools. A country that, according to one watchdog estimate, owes First Nations kids somewhere between $900 million and $2.9 billion for scooping them from their families then placing them in a broken child welfare system outside their communities.

Some are overtly political, like Article 26, which says Indigenous peoples “have the right to own, use, develop and control” their traditional territories. Others are less so and deal with protecting, preserving and promoting culture.

The UN describes the document as a tool for ending human rights violations, a global commitment to move forward. But, ultimately, these articles are not legally binding.

What would this legislation do?

If passed, the statute would affirm UNDRIP applies in federal law – meaning people can cite it in court – and create the framework for implementing it.

Ottawa would have to “take all measures necessary” to ensure federal laws are consistent with the declaration. Government would have to table an action plan within three years and report annually on progress made implementing it. This all must happen in thorough partnership, consultation and co-operation with First Nations, Metis and Inuit.

Observers, experts and policymakers look for a bellwether in British Columbia, which passed a similar law in 2019.

The statute afforded little aid to the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who opposed construction of a pipeline through unceded territory. They never surrendered a hectare, fought decades in court for land title, won a favourable ruling in the watershed Delgamuukw case – yet they found themselves asserting jurisdiction through blockade.

As the experts explain, there are gaps. Important ones.

Outside the lofty preamble, it doesn’t directly address the underlying issues that pushed the Wet’suwet’en onto a snowy, remote logging road to fight for land rights, the Mi’kmaq onto the sea to exercise a treaty right, or the Haudenosaunee onto a muddy construction site to fight for restitution of lands and cash lost to colonialism.

“It doesn’t address the issue of self-government, and it doesn’t envision power sharing,” said Abele. “The responsibility is on the federal government to introduce an action plan, and the words are consultation and co-operation in the development of that action plan. It’s not power sharing.”

It won’t make UNDRIP itself a law, only create process to make Canada’s laws compliant with its articles.

“It doesn’t deal with any of the really outstanding sticky issues, such as free, prior and informed consent. Does that mean, in certain circumstances anyway, a veto? Or does that mean consultation?” Abele continued.

“If it means consultation, who decides whether the consultation has been adequate? And there is no guidance in this legislation on that point.”

Nor would the bill’s first draft create new ways for Indigenous people to hold governments accountable outside of the action plan and reporting, according to Borrows.

“The accountability mechanisms are more to Parliament and Indigenous peoples, as opposed to an accountability mechanism being with the court,” he said.

Borrows points to Native American gaming rights in the U.S. as an analogy.

“There was a recognition that First Nations have the right to engage in high-stakes gambling, and they could enter into negotiations with the states and federal government to get that recognized,” he explained.

“If the negotiations broke down there was a process where you could sue to say that things weren’t being done in good faith, and so that created some judicial mechanism for accountability. Here we don’t have a mechanism to sue if good faith is not being exercised.”

And where else, still, does it fall short? Borrows replies that an UNDRIP law, ideally, could create an independent framework of processes and rules that help resolve disputes and prevent blockades. But, as currently written, this one doesn’t.

Nevertheless, Borrows – an eminent legal scholar and member of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation – sees the legislation as a good thing. Another resource in the toolbox of Indigenous human rights.

“What we’ve got is a lot of blunt instruments: big, general constitutional provisions recognizing some vast but ill-defined ideas around rights and title,” he said. “This is going to probably create some more fine-grained, granular possibilities to get where we want.”

But not everyone sees it that way.

Bill C-15 is a normal statute of the federal Parliament, so it must comply with Canada’s “supreme law,” the Constitution.

Repatriated from England in 1982, the Constitution limits government power and guarantees baseline civil liberties through its first 34 sections, known as the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

It also recognizes the rights of First Nations, Metis and Inuit through Section 35, which declares, “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

Using this short sentence, in 1999 the high court overturned the conviction of a Mi’kmaw man named Donald Marshall Jr. who violated the federal Fisheries Act by catching and selling eels out of season, ruling a 239-year-old treaty of friendship still applied.

Twenty-one years later, the Fisheries Act says nothing about treaties, and the Mi’kmaq and Ottawa remain far apart, in some cases in active conflict, on implementing the treaty right.

So what happens to the Fisheries Act if C-15 passes? Or, for that matter, the Indian Act? Or any law that violates UNDRIP?

“Those laws would be considered inconsistent with this statute, and therefore they’d have to be repealed or amended to bring those laws consistent,” said Borrows, “and that repeal or amendment has to occur in consultation with Indigenous peoples. The government can’t just do that on their own.”

Why oppose it then?

According to the first draft, C-15 “is to be construed as upholding the rights of Indigenous peoples recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and not as abrogating or derogating from them.”

Critics say that this essentially “Canadianizes” or “domesticates” UNDRIP and waters it down. The Constitution, while recognizing Aboriginal and treaty rights, also places stringent limitations on them.

“It entrenches the status quo by blunting the force and effect that UNDRIP has as an international legal instrument,” said Grand Chief Joel Abram of the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians (AIA).

The organization, which represents seven nations in Ontario, vocally opposes the bill. A day after he called C-15, “another White Paper,” APTN News reached out to Abram to find out why.

“We just can’t agree with the way it is right now. There’s opportunity there for it to be good. But they’re domesticating UNDRIP, and it’s just going to entrench Canada’s control over First Nations people and the land and resources,” he answered.

“The Sparrow test will continue to apply in all instances related to Section 35 rights and UNDRIP articles can be easily overridden in the name of national interest.”

The Sparrow test flowed out of another 1990 landmark high court ruling that overturned Musqueam man Ronald Edward Sparrow’s conviction under the Fisheries Act. It lays out when Ottawa can justifiably infringe or impose upon Aboriginal and treaty rights.

In the 2014 Tsilhqot’in ruling – which granted the nation Aboriginal title to a swath of land in central B.C. – the justices said the provinces too can override Aboriginal rights if they have a compelling reason to do so.

In other words, Aboriginal rights, as enshrined in the Constitution, are not absolute. Canadian sovereignty underlies them and governments can override them if they have a good reason why, according to the courts.

UNDRIP’s final article raises a similar issue for some.

“Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, people, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act contrary to the Charter of the United Nations or construed as authorizing or encouraging any action which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent States,” it reads in part.

“Right there, you can see that Canada will exercise veto over our determinations and our decisions, which is inherent rights that we have,” Chief Dean Sayers of Batchewana First Nation told the AFN assembly. “So, I would look forward to more empowering our assertion of law, and we take the unextinguished position of the first laws on these lands.”

Read More:

Canada tables legislation to align federal laws with UNDRIP

UNDRIP bill becomes law in B.C. after it fails federally

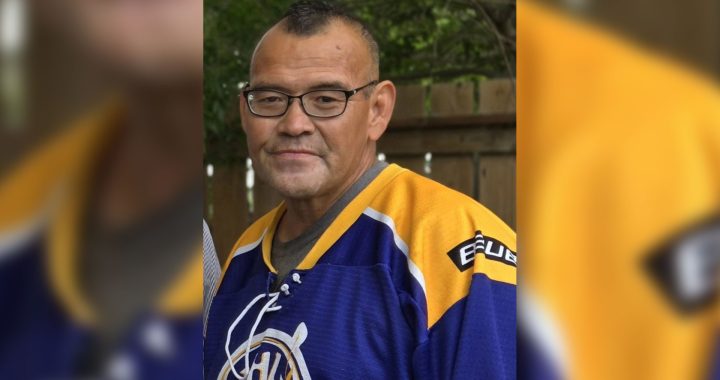

“I’m very careful in terms of what I’m going to accept from Canada, because historically they have not treated our people in a very good way,” added Chief David Monias of Cross Lake in Manitoba.

“Developing a legislative framework that applies to them – including all the provinces and the judicial systems that are in place – then yes I applaud them for doing that. But not, in any way, does this change any of our positions as sovereign nations.”

Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, a prominent lawyer and former judge who joined Littlechild at the assembly to address these concerns, acknowledged the trepidation.

“I am aware of the fact that there are some chiefs and organizations that reject Section 35 and reject the full box of Section 35 approach,” she said.

“I understand that there is great mistrust of the Crown – and so there should be great mistrust of the Crown – but there are courageous and important opportunities that are created by respecting and advancing the full box of Section 35, including absolute affirmation of treaties.”

What happens now?

The bill is only in first reading in the House of Commons. It has to be read another time, studied by the appropriate parliamentary committee, and read a third time. Then it must go to the Senate for consideration. After that it would go to the governor general, who can give it “royal assent” at which point it becomes law.

The government promised to table this legislation after a private member’s bill by then NDP MP Romeo Saganash passed through the lower house. It had a great deal of momentum before crashing into a wall of Conservative opposition in the Senate.

Many accused them of engineering the bill’s demise by preventing a final vote. When Parliament was dissolved for the 2019 election, Saganash’s UNDRIP bill dissolved with it.

Shortly after Justice Minister Lametti tabled the new bill, Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan released a joint letter they sent him and Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett urging them to delay.

“The draft bill can harm all communities, industry sectors, services, and Canadians,” said the letter signed by each provincial Indigenous affairs minister. “Canada needs investor confidence now, especially when so many people are depending on a decisive economic recovery.”

Lametti said the fears were misplaced when he announced the new bill. First Nations, Inuit and Metis leaders also brushed perceived “fearmongering” aside.

Added Abram, “A lot of the conservative provinces are against it because they think it goes too far – and we think it doesn’t go far enough.”

An UNDRIP law won’t overturn Supreme Court rulings on the duty to consult and accommodate. It won’t alter the “supreme law” of Canada, even though “amending the Constitution to bring it into conformity with UNDRIP” is what the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls inquiry actually called for.

The six provinces, all right-leaning, suggest it will afford Indigenous people too much power and create “uncertainty and litigation.”

But, suggested Bennett, a good deal of that already exists.

“The jurisprudence has been clear,” she said on the need for an UNDRIP law. “Way too much time and money has been spent by governments and industry to lose in court.”