B.C. First Nation files Aboriginal title claim challenging fish farms in their territory

The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation of Kingcome Inlet filed a claim of Aboriginal title in British Columbia’s Supreme Court that affects ten fish farms in their traditional territory that they say are operating without their consent.

(Dzawada’enuxw leaders outside BC Supreme Court in Vancouver. Photo courtesy Lindsey Mae Willie)

Laurie Hamelin

APTN News

The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation of Kingcome Inlet filed a claim of Aboriginal title in British Columbia’s Supreme Court that affects ten fish farms in their traditional territory that they say are operating without their consent.

“We have been saying no for 30 years,” says Lindsey Mae Willie of Dzawada’enuxw First Nation. “We have always said no and they just plunked themselves into our territory anyways.

“By going for title they will have to listen to us.”

Jack Woodward, the nation’s lawyer, is a leading expert in Aboriginal law.

Woodward represented the Tsilhqot’in Nation in the first successful claim of Aboriginal title in 2014.

“Once a precedent is set the procedural barriers are largely eliminated,” says Woodward. “It’s very much like an icebreaker clearing a path through the ice.

“The Tsilhqot’in did that and it now makes it much easier for those First Nations that follow.”

Although this new claim could take years to go through the courts, filing now puts added pressure on the provincial government, who has the power to grant fish farm tenures.

Most of the ten fish farm tenures involved in the claim, along with others in the Broughton Archipelago, are up for renewal in three weeks.

“Certainly one of the motivations is to file a claim prior to the June 20 expiry of the tenures,” says Woodward. “The Dzawada’enuxw want to clearly signal that they will not tolerate the renewal of those tenures.

“The province should not consider renewing in the face of this competing claim of ownership of the territory.”

The Dzawada’enuxw believe that open-net fish farms pose a serious threat to wild salmon and have been actively protesting against the industry since last year.

“We have tried everything we can to protect our salmon,” says Willie. “We’ve had marches, demonstrations, handed out eviction notices, we even occupied a fish farm, Midsummer Island, but got kicked off through an injunction last December.

“Now, that same fish farm company is trying to keep First Nations and everyone else 20 meters away from all of their farms.”

In early May, Marine Harvest Canada applied for an injunction that would prevent the public from coming within 20 metres of its 34 fish farm facilities on BC’s coast.

In legal notices, Marine Harvest alleges that Alexandra Morton, an independent biologist, and protesters “combined and conspired with each other with the intent to injure Marine Harvest by entering into an agreement to interfere and disrupt Marine Harvest’s business and to intimidate Marine Harvest and its employees to destroy the business of Marine Harvest.”

The injunction hearing is adjourned to June 25.

Greg McDade, the legal council for Morton, warns that Marine Harvest is trying to control the open ocean.

“They are asking for something fish farms should not have the right to do,” says McDade. “Which is the ability to control the public at large, and scientists and divers, from observing while outside the pens.

“Nobody can give ownership of the ocean, this isn’t like land. Under English Law going back to the Magna Carta, public access to water was always guaranteed.”

Molina Dawson, who grew up in Kingcome Inlet and occupied Midsummer Island fish farm for several months, says Marine Harvest’s desire to keep people away is concerning.

“Why don’t they want eyes on them,” asks Dawson. “The industry says their farms are not affecting wild fish, but the fact that they are trying to take measures to prevent people from observing from on and under the water, to prove or disprove that fish farms are doing or not doing something harmful, well that says a lot.”

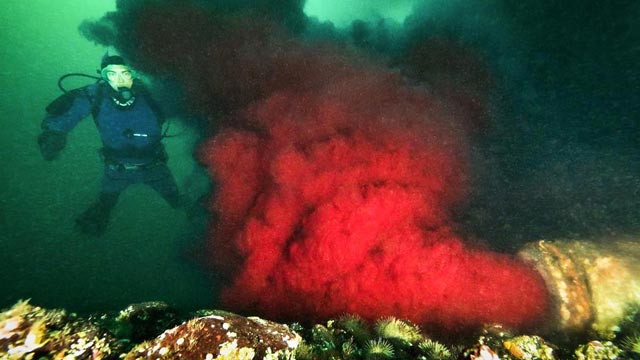

Dawson is referring to underwater footage recently shot by Tavish Campbell.

Campbell’s images of bloody effluent billowing from pipes at two fish processing plants off Vancouver Island went viral last November.

And in April, Campbell’s footage of a rare glass sponge reef smothered by fish farm waste, owned by Cermaq Canada, was released.

“That’s the real target of the injunction,” says McDade. “I think it’s underwater photography that’s starting to get to them.”

This month is a crucial time in the fish farm dispute.

If First Nations opposed to salmon farms don’t come out on top, the Dzawada’enuxw are confident they will finally win the battle in their title case.

“If we don’t stop the fish farms this month,” says Willie. “They’ll eventually see that we’re the rightful owners of our land and waters in the court decision.”

As a fly-fishing angler, I have practiced my sport along the south western BC coastal beaches, for the past forty years. I have watched the rapid decline of salmon and sea-run cutthroat trout, especially within the last fifteen years. I have noted the same decline in in my native Ireland, Scotland and Norway, when open-net fish-farms were introduced in the early ’80’s. Regardless of claims made by the fish farming community, they contribute very little to our economy, while anglers like myself, who release 90% of our catch do, by our travel, accommodation and other expenses. The negative impact from fish farms cannot be underestimated.

As a fly-fishing angler, I have practiced my sport along the south western BC coastal beaches, for the past forty years. I have watched the rapid decline of salmon and sea-run cutthroat trout, especially within the last fifteen years. I have noted the same decline in in my native Ireland, Scotland and Norway, when open-net fish-farms were introduced in the early ’80’s. Regardless of claims made by the fish farming community, they contribute very little to our economy, while anglers like myself, who release 90% of our catch do, by our travel, accommodation and other expenses. The negative impact from fish farms cannot be underestimated.

You don’t own the water you don’t own the ocean

You don’t own the water you don’t own the ocean