In Quebec, they’re called “Bebes Fantomes,” or ghost babies – dozens of Indigenous infants who disappeared without a trace after being displaced thousands of kilometres for hospitalization outside their home communities.

Fingering a threadbare tikanagan – or cradleboard – Manon Ottawa thinks of the uncle she never knew.

Paul Joseph Maxime Ottawa was born in Manawan in 1954. Though he would’ve been 67 this year, he’s still referred to in conversation as “Bebe Maxime.”

At six months old, the village priest requested that Maxime be transferred to a hospital in Quebec City to assess his eczema – a normally treatable skin condition.

“In Manawan, there were no phones,” Ottawa told APTN’s Nouvelles Nationales. “There was nothing to communicate with, no way to receive communication from the hospital. Only the priest had a phone.”

After two years without news, the family was informed that Maxime had died.

They never recovered his body; no death certificate was provided. But Manon Ottawa continues her search, compelled by a promise she made to her father while he was dying.

“He made me promise to search for him,” Ottawa explained. “To find or to trace his little brother.”

“What really happened to them remains a mystery”

A 175-page supplement to the MMIWG inquiry’s final report addressed the testimony, and chief concerns, of First Nations, Metis and Inuit people living in Quebec.

In the 1950s and 1960s, several Atikamekw families expressed similarly distressing circumstances.

In Manawan alone, an estimated 47 children went missing or were pronounced dead within this time period.

But the examples of missing children extend into other communities in Quebec; in a one year period, between 1971 and 1972, for example, eight children from the Innu community of Pakuashipi disappeared after admission to a hospital in Blanc-Sablon.

“The impact on the families is tremendous: depression, suffering, constant questioning, guilt, addiction, and more,” an excerpt from the Quebec report reads. “The families want answers and assistance. Today, the families feel a deep sense of injustice and want their stories to be heard.”

“The fate of these children, and what really happened to them, remains a mystery,” according to the report.

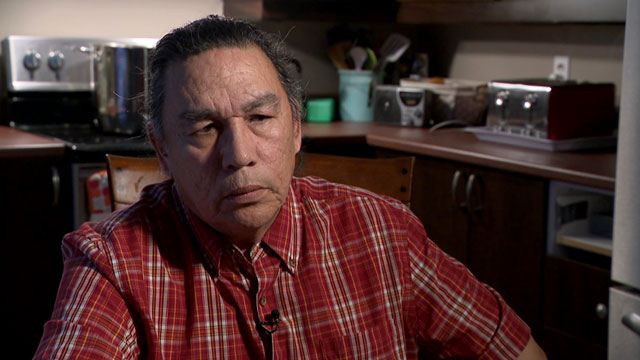

(Manon Ottawa holding the tikinagan – or cradleboard – that represents her missing uncle, Bebe Maxime. She says it will not be wrapped until they have news of him)

The commission heard several of these stories from parents in the Atikamekw communities of Manawan, Obedjiwan, and Wemotaci in the Mauricie region of Quebec.

Baby Pierrette, born in 1964, was hospitalized in La Tuque for digestive issues, but visited frequently by her parents.

Pierrette was transferred to Sainte-Justine hospital in Montreal without their consent.

When her parents returned to Wemotaci from a visit, the village priest informed them that Pierrette had died, and there was “no point” in trying to recover the body, according to testimony included in the report.

When baby Alice was born in the early 1950s, her mother heard the first cries and saw what appeared to be an overall healthy baby. But hospital staff took Alice to another room, and returned shortly to say that the child was dead.

Alice’s body was returned to her family in a casket with the top screwed shut. Other families received little more than a photograph of a closed casket as proof their child had died.

Baby Boivin, born in 1952, cried at birth. But doctors told his mother that he had died. A death certificate later listed baby Boivin as a “stillborn.”

These stories, according to the report’s authors, are “not unique.”

“Some witnesses are convinced that the babies were kidnapped to be used in medical experiments or sold to non-Indigenous families,” the report outlines. “The testimonies concerning these disappearances of First Nations children in Quebec are a reminder that the actions of governments and churches at the time were aimed primarily at assimilating Indigenous peoples into Canadian society.”

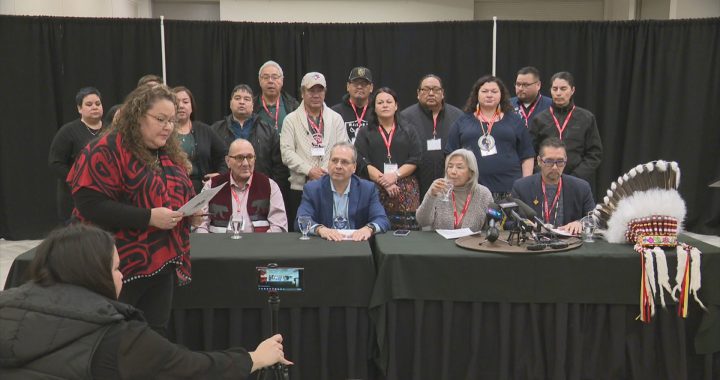

In the MMIWG inquiry’s calls to action, the Quebec-specific report directly addresses these concerns – calling on the provincial government to “establish a commission of inquiry” on children taken from Indigenous families.

It also calls upon the provincial government to provide Indigenous families with “all the information it has about children who have been apprehended following admission to a hospital or any other health center in Quebec.”

In November 2019, provincial Health Minister Danielle McCann tabled Bill 31 – an act meant, in part, to “[facilitate] access to certain services and to authorize the communication of personal information concerning certain missing or deceased Aboriginal children to their families.”

If passed in the National Assembly, it would facilitate access to health and social service documents for Indigenous children who went missing between 1950 and 1989.

While there is hope that this amendment will eventually bear fruit, Premier Francois Legault’s recent legal challenge of Federal child welfare legislation has shaken the confidence of First Nations leaders.

Still-grieving family members also say that even the hospital’s paper trail sometimes has a dead end.

“We say it has to change”

The Niquay household in Manawan is almost constantly in “investigative mode.”

Pierre-Paul Niquay – an outspoken advocate for the missing children in his community – lost two older brothers in unclear circumstances.

He has spent years poring over documents looking for answers. That is, when he can get his hands on them.

“When I called to obtain the documents, it seemed that everything was accessible. They told me to go to medical records,” Niquay explained. “When I arrived at the hospital in question, I went to medical records, and they told me it wasn’t possible to obtain the documents.”

His petition for release of the documents concerning his brothers’ hospital stays was denied, he says. Fighting these decisions normally requires a lawyer, paid for out of pocket – which, for many families, is not an option.

Even when obtained, records are often rife with inconsistences. Government-issued death certificates spread out on the Niquays’ kitchen table tout three different dates of death, for example.

(‘If there are deaths – where are they buried, our brothers and sisters? asks Pierre-Paul Niquay)

His wife, Viviane, also found out in adulthood that two of her siblings similarly vanished.

Her mother – forced to give birth in a sanatorium while being treated for pneumonia – delivered a boy and a girl, and always maintained that she heard two babies cry.

But the doctor at the time returned with bad news.

“My mother, from what she told me, never saw my sister’s body,” Viviane explained. “She asked the doctor to bring it to her, and he replied ‘it’s too late madame, we can’t do anything.’”

Together, the Niquays continue to advocate for the missing children, even holding a local forum in Manawan to address it. They’ve also advised other families in Manawan as to the resources available to them – but the research is long-winded, and the journey is arduous.

Delima Flamand, the proud matriarch of the Flamand-Dube family, today has six daughters.

She was supposed to have seven.

“It was vague, you know?” explained Denise Dube, one of Delima’s daughters. “We don’t know exactly what happened. What she had.”

Little Violetta, born in 1956, was taken from Delima shortly after birth, and pronounced dead. Her birth and death certificates, however, indicate that she died at almost a month old.

Carole Dube said they didn’t have any luck trying to obtain hospital records from Violetta’s stay.

“We left the hospital disappointed, because we had only one sheet. They told us the files were purged,” she explained. “We don’t know what happened. Medical files are usually kept for a long, long time.”

The Flamand-Dube family – who testified about their experiences at the MMIWG inquiry hearings in Montreal – also checked parish records and local cemeteries, and even the national archives in Ottawa.

(The Dube sisters all have matching tattoos (sister 2 of 7, and so on) But “1 of 7” is missing. Sister Violetta was taken from her mother’s arms in-hospital and pronounced dead. They still cling to the hope that she is alive and was adopted)

But all they found were Health Canada records, financial statements, and agreements – all written in English.

For years, this language barrier kept Delima – a first-language Atikamekw speaker – from finding out what happened to her child.

“She’d say ‘I don’t know what happened to my daughter. I never saw her again. They just told me she was dead,’” Denise explained.

“I said: they stole her. They stole her baby,” she added.

The remaining six daughters cling to the hope that their long-lost sister is still alive, and was adopted into a non-Indigenous household.

But without improved transparency and adoption of new legislation, dozens of families encounter the same roadblocks.

During the forum in Manawan in 2018, the community called for legal representation, psychological aid, and the creation of a DNA database to help with the search.

“For us, we say it has to change and address the family’s needs,” explained Pierre-Paul Niquay.

“We will look for certainties. Was there really a kidnapping? Or were there deaths?” he added. “And if there are deaths – where are they buried, our brothers and sisters?”

Manon Ottawa, for her part, says she continues to be affected by the unending thoughts of what the endless moments of anticipation must have been like for her grandmother in the days, months, and ultimately years following her child’s fateful plane ride away from home.

“My grandmother wrapped [Maxime] and gave him a blanket to board the plane,” she said. “The tikinagan was never returned to Manawan. They never received their baby’s personal effects. I always think of my grandmother checking for planes at that time.

“The mothers, every time a plane arrived, went towards the shore to see if their babies returned.”