A Potlatch held at the old Parish Hall behind the Anglican Church in Alert Bay in 1922. Photo courtesy: B.C. Archives

Almost 100 years ago, while many gathered with family members to exchange Christmas presents, several dozen Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people were arrested for holding a winter gifting ceremony of their own.

ʼNa̱mǥis Hereditary Chief Bill Cranmer says it was December of 1921 when his father Dan held a large Potlatch at ʼMimkwa̱mlis (Village Island) off Northern Vancouver Island that was interrupted by Indian Agents.

Under Canada’s Potlatch ban, holding the ceremony involving gifting, speeches and dancing, was illegal under the Indian Act between 1884 to 1951.

“What they were trying to do was destroy the structure of the society of our people by stopping us from carrying on with our ceremonies, our languages or songs and our history,” Cranmer says.

“That was the main reason why they banned the Potlatch and our peoples, the Kwak̓wala-speaking peoples, were the last ones to throw in the towel.”

The word ‘potlatch’ comes from a trade jargon, Chinook, and is used to describe a community feast held for a variety of reasons — the naming of children, marriage, transferring rights and privileges, mourning the dead, to name a few.

After the 1921 Potlatch was raided by Indian Agents, 45 people were arrested and charged, according to the U’mista Cultural Centre. Twenty community members were sent to Oakalla Prison Farm, outside of Vancouver to serve two or three-month sentences.

Cultural objects such as masks and regalia were confiscated and put into museums or private collections.

“It was pretty bad for our people to be taken from our community to be shipped down to a prison farm,” Cranmer says.

After the arrests, people in his community stopped gathering for Potlatches, he says. However more remote Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw communities continued to hold ceremony in secret, knowing it was difficult for Indian Agents and police to get to their territories.

Three decades after the arrests, the Potlatch ban was lifted. In 1952 Cranmer was able to attend a ceremony alongside his father at the first public Potlatch at the Mungo Martin House in Victoria.

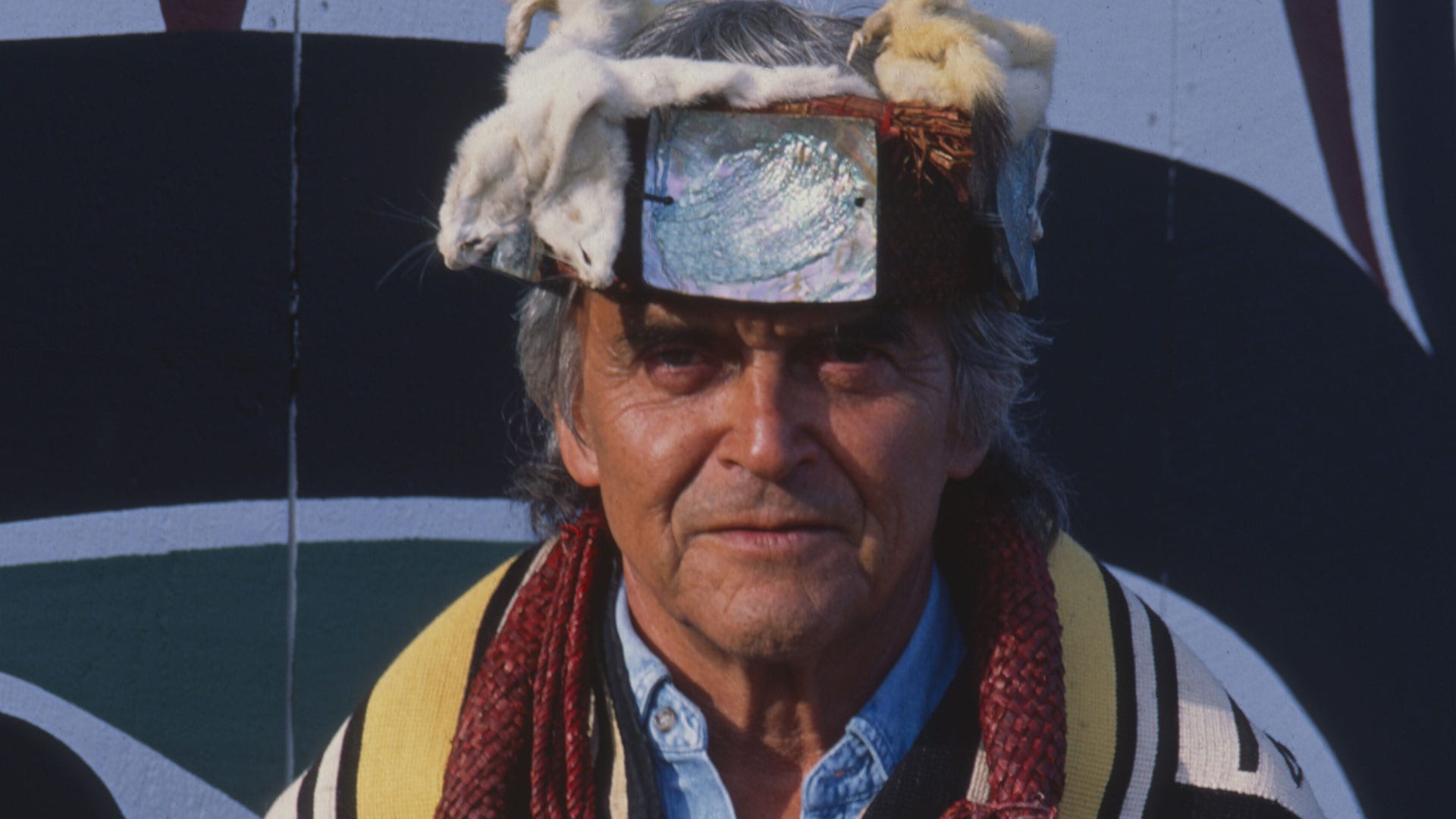

Now, Cranmer is the chairman of the board of directors for U’mista Cultural Centre, which was founded in 1980 as a place to house and preserve Potlatch artifacts seized by government agents during the ban.

Cranmer has been instrumental in repatriating these cultural objects back to his community and received a Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers from the Governor General in 2017 for his work.

Cranmer says there were various attempts in his community to see the ban lifted sooner.

At one point, he says, chiefs invited members of Parliament to witness a Potlatch so that they could see for themselves that there was nothing wrong, but no one showed up.

He says people in his community also drew comparisons to Christmas and the exchanging of gifts, but Indian Agents disagreed, saying Potlatch was different because it was ceremonial.

“When a chief has a Potlatch and invites guests, his guests are invited to be witnesses and the witnesses are given gifts for being there,” Cranmer explains. “It’s to mark certain special occasions.”

He says many fear-based misconceptions were spread about Potlatches by the church — including wrongly stating that cannibalism was practiced or young women were “given away.”

“They were the ones that were responsible for spreading all kinds of wrong things about our people to the government of Canada at the time,” he says, adding that it was all part of a wider assimilation effort.

“When our people were feasting and carrying on with our ceremonies they didn’t really have time to be converted to Christianity.”