Everything about the world’s first national Indigenous television network seemed destined for failure.

Asking the public to name it (the lucky winner received a Sony VCR), petitioning the Canadian Radio Television Commission (CRTC) for mandatory carriage and subscriber fees, producing only a weekly (not nightly) newscast.

Yet, the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) continues to defy critics as it celebrates 20 years this month.

“Remember, we weren’t supposed to succeed,” says Dan David, the first news director.

“We were supposed to fail. It wasn’t supposed to exist.”

The network was founded Sept. 1, 1999 in Winnipeg, Man., where it broadcasts a now-daily newscast to more than 11 million subscribers.

It produces a variety of news and current affairs content on air and online, operates two radio stations (in Toronto and Ottawa), while its reporters regularly win national journalism awards alongside Canada’s mainstream media outlets.

Failure, it seems, was not an option.

“The stakes were so high,” said David, an award-winning journalist and media trainer.

“We knew that if we failed… we wouldn’t be failing a network, a corporation, a company, we would be failing all Indigenous people – not just for now but for generations to come.”

It was against that backdrop that APTN unveiled its original broadcast schedule in April, 1999 on two channels: APTN North and APTN South.

“It was a combination of ancient classics from the National Film Board, re-runs of movies featuring any Indigenous actor in any role, and Northern Native Broadcast Access Program (NNBAP) programs – some of the first original Indigenous programming produced in Canada,” recalls Jean LaRose, APTN’s CEO since 2002.

Timeline: A look at APTN over the past two decades

If timeline does not appear, click here

It was NNBAP – a federal government initiative that funded television and radio stations run by 13 Indigenous communications societies across the North – that helped pave the way for APTN.

It lobbied hard for money and equipment to make its own programs – the way it was done in the South –claiming shows pnly in English with mostly white faces was helping erode Indigenous culture.

But they needed a cable operator to carry their shows.

– Jocelyn Formsma.

After years of meetings and negotiations (and tears, according to some), a new organization called Television Northern Canada (TVNC) was formed, which eventually applied to the CRTC to establish an Indigenous broadcaster.

“However, it did not come without a fight,” notes Jocelyn Formsma, chair of APTN’s board of directors.

“They had to convince the CRTC that Indigenous broadcasting was vital to Canadian broadcasting.”

In 1998, the commission was convinced.

It approved a national broadcast licence with a distribution model never granted before – making APTN a mandatory service and allowing it to collect subscriber fees.

(In 2018, APTN was instrumental in launching two radio stations. One in Toronto and the other in Ottawa)

Something a CBC executive (and former commissioner with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada) opposed.

“Marie Wilson, Director of CBC North, was dubious about the potential for revenue generation,” writes Jennifer David, the network’s first director of communications in her book “Original People. Original Television: The launching of the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network.”

“She pointed out that CBC was considered a public broadcaster with a nationally licensed network on basic cable, but didn’t collect subscriber fees. ‘How can TVNC become a public, national network,’ she asked, ‘and at the same time ask for subscriber fees?’”

The answer was that TVNC – and ultimately APTN – would set a precedent and do both.

There was no doubt, APTN benefited from and would later improve upon the southern programming being beamed into northern communities via satellite.

Rosemarie Kuptana, an early member of the Aboriginal broadcast movement, described the introduction of television to Inuit communities as a “neutron bomb – one that leaves the outer shell of the people walking around but kills the soul.”

Jennifer David, in her book, says the new medium was completely disconnected from northerners, with “only the rarest glimpses of themselves – and always through southern eyes.”

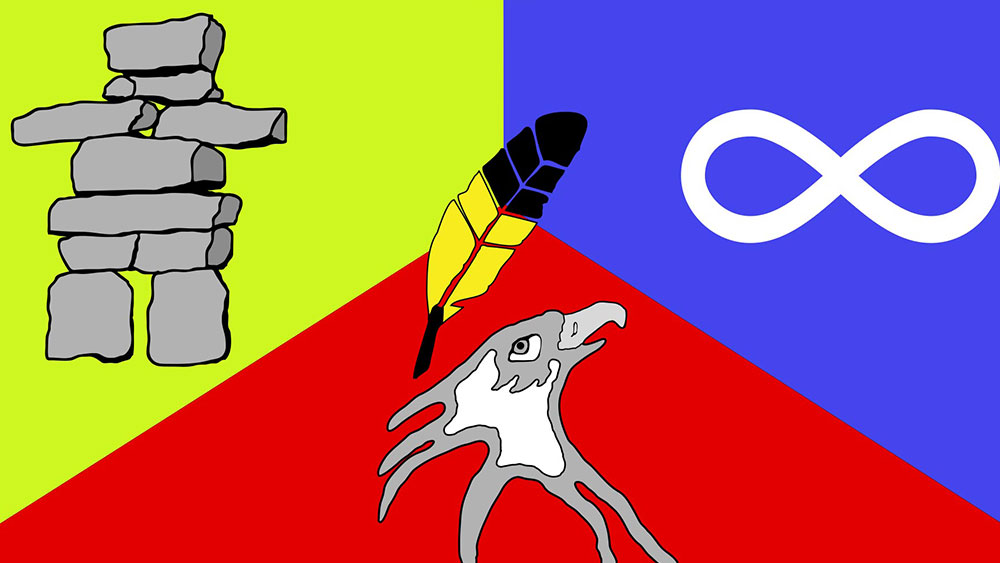

“Aboriginal people are the original inhabitants of the land we now call Canada. So how did Aboriginal Canadians become the outsiders?”

(Indigenous Day Live shows run across the country and the network)

APTN’s future was never assured or secured. It still appears regularly before the CRTC to defend its mandate and, sometimes, very existence.

But it is no longer a baby.

It is a 20-year accomplishment representing a generation of Indigenous television, with a core audience in thousands of Indigenous communities.

“If you want to look at numbers,” wrote its editorial employees in a submission to the CRTC in 2005, “then what you should look at is the number of communities that have been enfranchised with access to a mass medium free press through the arrival of APTN.

“In fact, in our opinion, the sheer number of communities where people are tuning in to a directly relevant national media – and the possibility of local coverage – has grown more through APTN‘s first licence period than at any time since CBC first went on the air.”