Gerald McIvor’s brother Michael was just four years old when he was sent off to Manitoba’s Ninette Tuberculosis Sanatorium in 1952. He spent four years there, mostly on bed rest.

Shortly before Michael McIvor died in 2000, Gerald McIvor vowed to help uncover what happened to him there.

“I promised my brother,” he said. “Our brother was our protector but he didn’t have a protector.”

Gerald McIvor started a Facebook group to gather alleged victims of medical experimentation and said he is in the first stages of organizing a class action lawsuit.

“It is really driving home my ambition to see that these people have answers – they get some closure,” said McIvor. “More importantly they get judicial redress for what was done to them. These are little children, humans, not guinea pigs.”

APTN Investigates travelled across the country, digging through archives and visiting the sites of former so-called Indian hospitals and tuberculosis sanatoria.

McIvor recalled his brother describing procedures that sounded to him, like medical experiments.

“He would share vivid details of what happened,” he said. “Carts brought into the dormitories with little bottles of different coloured liquids, with medical staff standing around them with clipboards, documenting every reaction.”

“It brings us a lot of memories,” said McIvor in an interview with APTN at the old site of the sanatorium site just south of Brandon, Man. “It is very peaceful but deceiving.”

The hilly seven-acre Ninette site is surrounded by a trailer park and other private homes, making it difficult to find.

Six of the original 12 buildings still stand, though just the administration building was open at the time. Inside, examination tables, machines and even medical instruments still stand.

“I call this my summer cottage,” laughed Ronnie Aschenbrenner, the current owner who bought the property from a local man in 2008.

She intended to open it up as a retreat for artists and writers but the cost of restoring and maintaining the century-old buildings was too high

Aschenbrenner is now selling the huge complex for just $575,000.

McIvor said it should be declared a historical site.

“This is a painful historical place for our people,” he said.

The sanatorium opened in May 1909 and according to archival records, the Sanatorium Board of Manitoba took over the epidemic of tuberculosis amongst the Indigenous population starting with a survey of reserves in 1937.

Click here to read letter from Dr. Edward L. Ross, Sanatorium Board of Manitoba

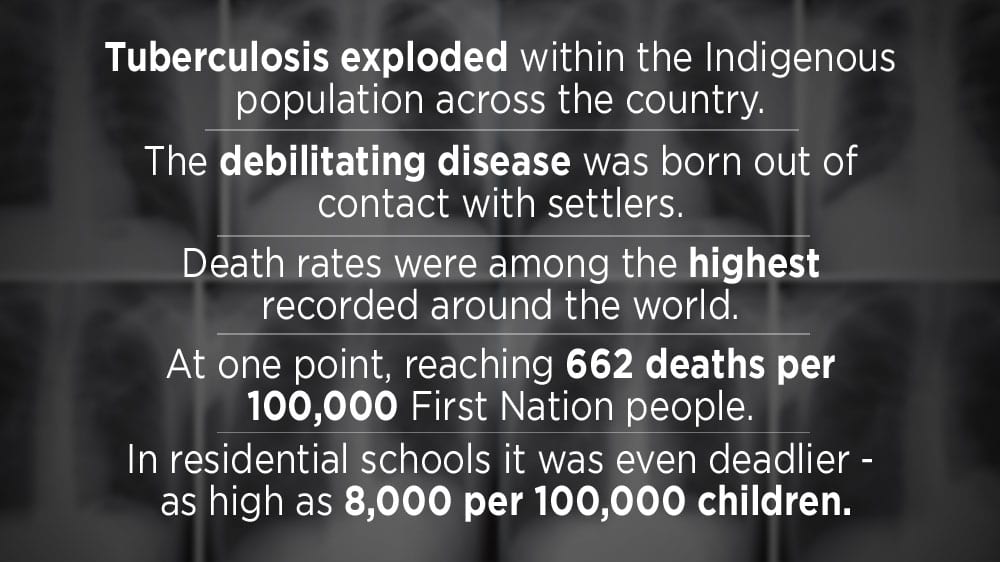

Tuberculosis is bacterial infection that spreads easily through the air. It had decimated the Indigenous population in Canada from the time of contact. Wracking coughs, fatigue, and weight loss are all symptoms. It can also lay dormant for years and then re-emerge. Advanced TB can cause holes to form in the lungs but it can also affect other parts of the body.

Antibiotic drugs were eventually developed but until then, the only cure was sanatorium rest. Surgeries like rib and lung removal would also be used in advanced disease.

“There’s a lot of trauma that communities and individuals experienced at these institutions about residential schools,” said Ian Mosby, a Toronto-based researcher. “Where I’ve been spoken at events and been at events where survivors are speaking, Indian hospitals invariably come up.”

He uncovered evidence of shocking nutritional experiments on Indigenous children at residential schools and points out that a full inquiry should be called into Indian hospitals and TB sanatoriums.

“Because the barrier between Indian hospitals and residential schools was very fluid.” he added. “It’s important that we listen to survivors.”

(The Road to Recovery was a film produced by the Sanatorium Board of Manitoba, 1950. Archives of Manitoba)

“I guess my worst fear is the memories coming back…”

Alberta Families searching for tuberculosis hospital records

Dorothy Wanihadie has a hard time remembering her time at Edmonton’s Charles Camsell Hospital but her daughter Victoria is determined to find out what happened.

Wanihadie was just three years old in the 1950’s when she was taken from her family home on Alberta’s Horse Walker First Nation, about 400 km north Edmonton.

“My mother said I wasn’t sick,” she said. “’They just took you.’”

“I guess my worst fear is the memories coming back,” she said. “I don’t think I can handle that.”

Wanihadie was one of the thousands of First Nation and western Inuit patients treated at Charles Camsell Hospital.The hospital had been a Jesuit College and then briefly a veterans’ hospital before becoming in 1946 the largest medical referral centre for Indian and Inuit, mostly diagnosed with tuberculosis.

She said she knows she was treated for tuberculosis but other details elude her.

“I called and they said they didn’t have any record of me and that was it,” she said, referring to a call she made to the Alberta Health Service.

But that’s not good enough for daughter Victoria.

“These people they need to heal, they need to find out what happened to them,” she said. “They need to start healing.”

Planes equipped with X-ray machines would fly to remote communities and screen for the disease. If tuberculosis was detected, patients were shipped to the hospital from all over the north and the prairies.

A new building was completed in 1964-65 and then condemned in part due to asbestos in 1996.

Click here to read a patient’s account at the Charles Camsell Hospital

Marilyn Buffalo’s grandmother Harriet Buffalo was a hospital patient and then an employee in the food service area in the hospital.

She wants the federal government to turn over the hospital records of her grandmother and great-grandmother as well as all the other patients of the federal hospitals.

“It was very hard for the staff,” she said. “One day the patient would just be gone and no one would be told what happened. There was no closure for them.”

Until 1990, the graves of Inuit patients who died at Camsell Hospital were unmarked. Buffalo’s step-father recalled digging graves there when he was a student at the nearby Edmonton Residential School.

Buffalo spent a lot of her childhood at the hospital and related that the patients were often isolated, confused and homesick.

“Very few families had the means to come and visit them, especially from the north.” She said. “It’s wrong. Very wrong.”

From the North to Hamilton, Ontario

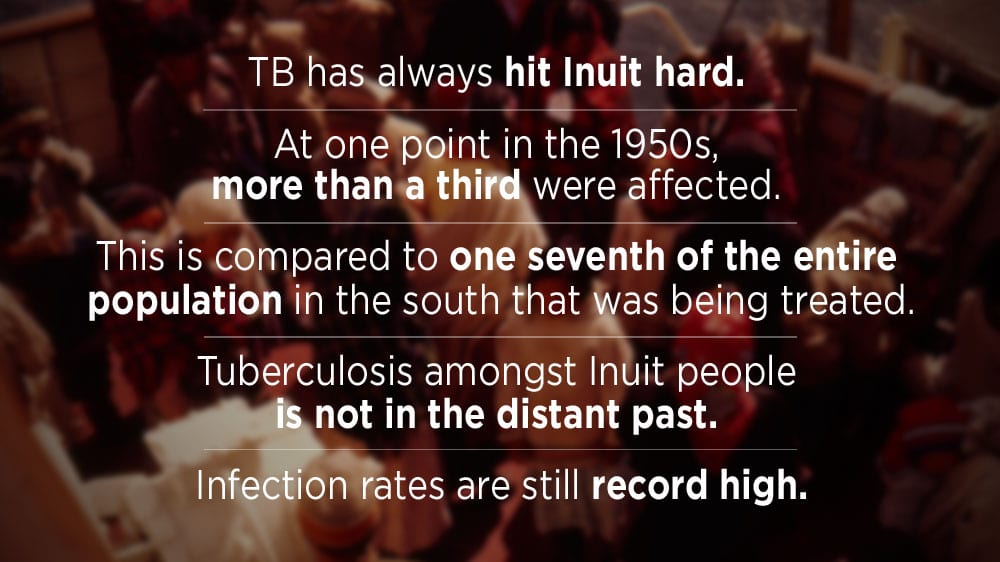

At least 1,200 Inuit from the Eastern North were shipped to Hamilton’s Mountain Sanatorium between the 1950s and early 60s.

They made a months-long journey aboard the C.D Howe ship, an ice-breaker, where living conditions were cramped and often smoke-filled. Bags filled with potentially TB infected spittle would hang over the side of their bunk beds

Once admitted, patients were confined to bed rest, often for years and produced a remarkable collection of more than a hundred Inuit sculptures now part of an Art Gallery of Hamilton exhibition.

Author Shawn Selway’s book, “Nobody here will harm you- Mass Medical Evacuation from the Eastern Arctic” chronicles the ship’s perilous route from the far north to Montreal and then by train to Hamilton.

“If you were diagnosed with Tuberculosis in Cape Dorset and returned by ship all the way to Montreal,” he said. “You would be quite a while down below deck,”

Inuit patients were assigned an identification disc.

“To make it easier for the administration, Selway explained. “People had a number so one person one number, it was one name, one number and you can see that there is a hole there, so you were supposed to wear that around your neck.”

McMaster University records show that Inuit patients were also good for business.

Filling beds left empty by cured Caucasian patients.

Dr. Hugo Ewart worked at the Mountain Sanatorium for decades – and left behind a memoir found in the archives of McMaster University.

“Just as the decline took place, we got a call from Ottawa asking if we could take a few Eskimos. We said how many? They said about 50 patients probably. We ended up with 352 – I think that was the high point.” the memoir stated.

“When they were bringing people out very rapidly without an opportunity to make arrangements for those people left behind, and those communities are very tight-knit, with lots of adoptees, and so when you start taking people out of there is caused a lot of problems and it caused a great many problems for the people who were moved because they didn’t know what was happening back home,” Selway added.

Men were given soapstone to carve – women made dolls.

“The depth and intensity of pain and anguish which they expressed I wasn’t prepared for”

International Aids advocate Stephen Lewis has seen a lot in his political and activist career.

But he was shocked by the history of Nunavut. He went to the north in his capacity of Director of AIDS-Free World because TB is a common secondary infection to HIV/AIDS.

“I wasn’t prepared for the outpouring, the emotional outpouring from the elders about what they had experienced with the sanatoria in the 50s and 60s,” Lewis told APTN. “The depth and intensity of pain and anguish which they expressed I wasn’t prepared for.”

“I wish there were ways of taking crimes against humanity into court because I think what the Canadian governments have done cumulatively against Indigenous persons across this country is a crime against humanity, I don’t know how else to characterize it.”

“They were swept down to the sanatoria and didn’t return, so the gnawing desperation of what was said, was rooted in the loss of family members, they didn’t know when they died, they didn’t know when they were buried, and they know the records exist but no one will tell them, So there is a kind of angry bewilderment.”

Lewis said he intends to bring the TB situation in Canada’s north into the international spotlight.

“The excruciating violations the racism around tuberculosis in the 50s and 60s has so traumatized the people to this day that it is part of the stigma, they don’t want to come forward and be tested and talk about TB they are afraid of the legacy the inheritance of what their parents and grandparents experienced.”

And like patients at the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton, those who died were buried thousands of kilometres from home. Many ended up in Woodlands Cemetery in Hamilton.

Families back home wouldn’t always be told when someone died and many still don’t know where their loved ones are buried.

But a fall 2017 task force announcement by Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott seems to offer some hope to Inuit. They have been working on a database of missing Inuit for a decade.

“This is not a new problem, Tuberculosis has been present in Canada’s Inuit for more than a century and we have seen not only those very high rates we have seen these terrible circumstances where people have had to leave their homes in the 1940, 50s and 60s that they were sent thousands of kilometers from home and their families many time s never knew what happened to them. And buried in graves that are unmarked. ” she said.

What about the other First Nation people sent to hospitals?

Indian hospitals and sanatoriums were left out of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement which is now winding down.

Joan Morris’ mother Mary spent 17-years at the Nanaimo Indian Hospital on Vancouver Island.

Doctors told her she had TB.

“They did mass experimentation on our people,” she said. “Lots of lost lungs and ribs.”

It was her testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that inspired author Gary Geddes to write Medicine Unbundled.

“Hearing that her mother had spent 17 years at the Nanaimo Indian hospital just staggered me,” he said. “I couldn’t get it out of my mind and when I had a chance to talk to her, and got even more of the information, It just seemed to me the story needed to be told.”

“She said the needle was that long, they put it directly in the belly button and injected them and an hour later, they blew up.”

And it was a point of pride for the government that care for Indigenous patients cost less.

“The government was quite happy to brag that they were able to handle Indigenous costs at 50 per cent of cost for the rest of the population,” he said.

“The wound is not healed …

But nothing is planned for other Indigenous patients who suffered.

Gerald McIvor said he hopes his lawsuit will spread across the country.

“The wound, the wound is not healed, It may be covered with a scab at the top but it is still festering inside,” he said.

Please don’t forget about NWT. My Grandfather was taken in the 1945-55 from Phedze Ke, NWT. He never came back home. Does Charles Camsell Hospital look familiar? Why always leave out the Dene from the North out.

Excellent reporting on this issue. Woliwon for those involved to bring this message forward. Woliwon Gerald McIvor for telling your story and bringing the truth to the table.