For the Abenaki, the black ash tree is sacred.

This has been true from time immemorial, but perhaps even more so today because black ash is also endangered.

The wood from the black ash is so precious, Chief Rick O’Bomsawin keeps Odanak First Nation’s supply in a vault.

“This is the ash after it’s been pounded,” explains O’Bomsawin, taking some off of a shelf as an example, “The men have cleaned it and from here the women will take this and make the baskets from it.”

For the Abenaki, the black ash tree’s importance goes beyond the material. A creation story describes the tree’s history with the Abenaki as literally intertwined.

“The Creator created the world,” explains O’Bomsawin. “There were flowers, there were plants. It was just a beautiful place. But there was no sound, there was no one to enjoy it. The Creator thought, ‘how do I create something beautiful, a beautiful people that can roam and dance and sing?’ He looked at his ash tree and he thought ‘wow, this is gorgeous. It’s blowing in the wind. It’s like it’s dancing.’ So he breathed life into the ash tree and created the Alnôbak, the Abenaki people. And to this day we still dance and sing along with the ash trees.”

In some ways, this creation story harkens back to simpler time…when it was easy to know who is Abenaki … and who isn’t.

In southwestern Vermont near the New Hampshire border, Rich Holschuh turns down a path into a wooded area.

“We’re going to walk down to the water there,” Holschuh explains. “The Abenaki name for this river is the Wantastekw, which translates as the river where something is lost.”

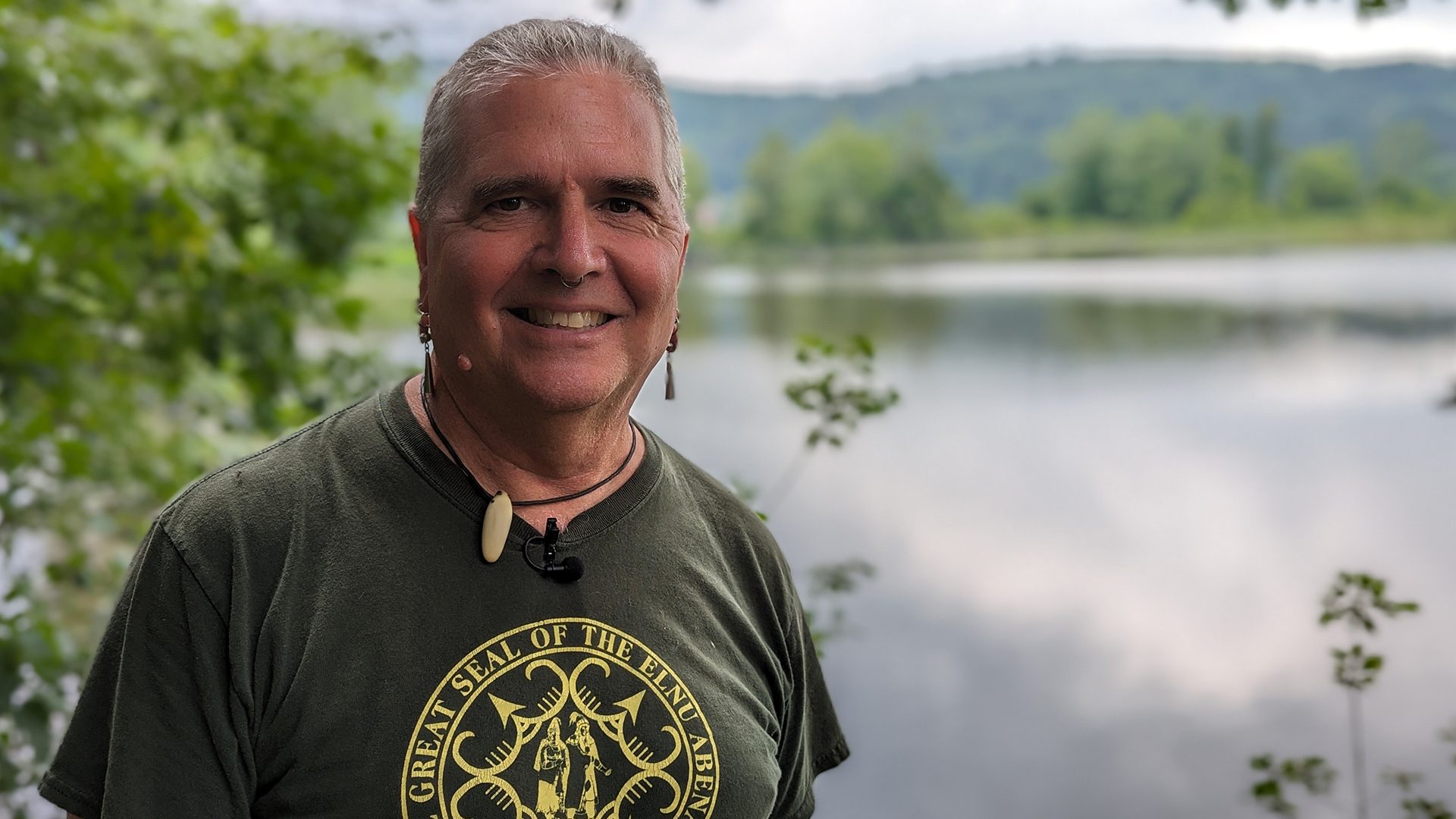

Holschuh is part of the Elnu Abenaki tribe, one of the four state-recognized Abenaki groups in Vermont. He says that prior to the construction of a nearby dam, this river was home to a whirlpool, which explains how Wantastekw became the “river where something is lost.”

Recently it became famous for something that was found … specifically a set of underwater petroglyphs.

“If you know a little bit about petroglyphs, they are placed in certain spots for certain reasons, the symbols that are down there are responding to the characteristics of this spot,” says Holschuh.

As a result, the Elnu consider this area a place to be safeguarded. Recently, the Elnu fundraised to buy a nearby property, with the goal of turning it into an Abenaki cultural centre.

A place to teach, learn, and grow their presence.

“The Abenaki were basically written out of history here, and in most people’s minds they’re gone and they live somewhere else,” says Holschuh.

This is where a quick history lesson is in order.

First, the section that most can agree on. Prior to European contact, the Abenaki were a loose collection of family bands. Their ancestral lands, Ndakinna (“Our Land”), bookended with Maine in the east and Vermont in the west, then went as far north as Quebec and stretched south to Massachusetts.

They are part of a larger confederacy of eastern First Nations, the Waban-aki confederacy. In the Abenaki language, they call themselves “Wôbanakiak,” loosely translated as: people of the dawn.

Aside from run-ins with the Mohawk, they are depicted as mainly peaceful, until their ancestral lands became the frontlines of warring colonial powers.

In the 1600s Abenaki mainly allied themselves with the French over the English, fighting six separate wars against the British in less than a hundred years.

But there’s a reason why a large chunk of Ndakinna is now called New England. In the mid-17th century, Abenaki began moving en masse to Quebec to flee wars and disease.

In 1700, Odanak was established in southeastern Quebec, followed eight years later by nearby Wôlniak. Back in New England, cunning Abenaki Chief Gray Lock won some victories against the English in the early 18th century. By 1725, some measure of peace was achieved.

But it was not to last. The late 18th century was marked by France ceding Quebec to the British and eventually, the American Revolution. Decimated by decades of war and disease, Gray Lock’s community of Missisquoi, located in Vermont just a few kilometres from the Canadian border, was abandoned by 1800.

Historians say that save for a few stragglers, the Abenaki of Missisquoi moved north to Odanak.

But here’s where opinions begin to differ.

Some say Abenaki communities continued to live on in the then-fledgling state of Vermont.

Nowadays, about 400 Abenaki live in Odanak and Wôlinak, about 130 and 160 kilometres northeast of Montreal respectively. But their approximately 3,000 members live all over Canada and the US, and many of them feel people like Holschuh have no business safeguarding petroglyphs or any other aspects of Abenaki heritage.

“To have an ancestor from 14 generations ago does not make you an Indigenous individual today. They played on the fact that ‘you just had to feel it in your heart,’ but that’s not how you become an Indian,” alleges Odanak band councilor Jacques Watso “If I like rice and Bruce Lee movies, that does not make me Chinese.”

The current dispute is going on 20 years, but initially when self-identified Abenaki from Vermont met Abenaki in Odanak in the 1990s for a cultural exchange, there was a honeymoon period.

“When they came to our community, we welcomed them with open arms and we taught them our culture, our language, our stories, our heritage,” alleges Watso. “When we started to ask questions on ‘who are you? How are you related It to people in Odanak, how are you related to the Abenaki Nation?’ They had no answers.”

Others from that period say it was a mutual exchange, that the late Homer St. Francis, a leader of the St. Francis/Sokoki Abenaki band, made lasting inroads with Abenaki from Quebec.

“He worked with people from Odanak. He had agreements with chiefs from Wôlinak and from Odanak,” says Chief Don Stevens of the Nulhegan band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation, one of the four Vermont-recognized Abenaki groups.

What is undeniable is that St. Francis, who died in 2001 at the age of 66, has a left legacy in Abenaki politics.

In the 1970s St. Francis helped launch the first self-identified Abenaki group in Vermont into the public eye. Located in the town of Swanton, near where the Abenaki community of Missisquoi once stood, the St. Francis/Sokoki band eventually won hunting and fishing rights for their members.

And while in 2007 they failed in their bid for federal recognition, they rebranded as the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi and eventually won state recognition in 2012.

Something that leadership in Odanak opposed from afar after their request to testify in front of state government was denied.

The reason? They weren’t citizens of Vermont.

“We didn’t have a voice on our traditional homelands, we were just basically pushed aside because we were a nuisance to the whole process,” fumes Watso.

The Abenaki at Missisquoi weren’t the only ones recognized. The Koasek Abenaki Tribe joined them in 2012, while the aforementioned Nulhegan band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation and Elnu Abenaki tribe preceded them in 2011.

Odanak’s band council passed a resolution in 2003 saying they no longer recognize self-identified Abenaki groups in Vermont. Their main gripe: they say the Vermont groups haven’t been transparent about their genealogy.

“If you ask an Indigenous individual in Canada or anywhere else, where are you from? He will tell you. He won’t tell you a story. He won’t tell you ‘it’s complicated’ each time,” says Watso.

Odanak leaders aren’t the only ones to raise red flags about the Vermont recognized Abenaki.

“The main dispute is that they aren’t related to who they say they are,” says Darryl Leroux, an author and professor at the University of Ottawa. Leroux’s work focuses on “race shifting,” a term for when a person claims an ethnicity that isn’t theirs.

He recently published a peer-reviewed paper about the four Vermont-recognized Abenaki groups where he did the genealogy of many of their members using a list of family names the Missisquoi group provided for the rejected 2007 US federal application for recognition.

“I think there are records for about 150 descendants,” explains Leroux. “And then I looked at their ancestors, so I went in both directions. And the results are that their ancestors are all from Europe. Except for a couple cases where people have some of the same ancestors I have, one of them is an Algonquin woman from the 1600s.”

The Algonquin ancestor Leroux shares is common amongst French Canadians, and he’s not the only one: about ten million Canadians have a small amount of Indigenous ancestry that can be traced to the same five to 10 First Nations women.

Leroux says about 60 years of census records also paint a monochrome portrait.

“What you find out is that every single time in every record where someone’s race is identified, everybody is identified as white,” says Leroux.

As for the 2007 Missisquoi federal application for recognition that Leroux gleaned the names from, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs determined that less than one percent of the membership had Abenaki ancestry.

“We grew up knowing we were Indigenous and Abenaki yes, we did some things together as family units but not in the public,” says Don Stevens, who has been chief of the Nulhegan for 13 years.

Stevens says he was formerly a member of the Missisquoi Abenakis, but only through marriage.

He says that it’s overly simplistic to say that today’s Vermont groups are offshoots of the group that was denied federal recognition.

He also resents Odanak’s accusations that he is not Abenaki.

“They’re not the only tribe. I mean if you look at things historically, there were 20 Abenaki tribes throughout history throughout New England. And so, they have no ultimate authority over who is Abenaki or who isn’t,” says Stevens. “I have enough people that recognize me as being an Abenaki and my mother and my grandmother made me an Abenaki. So, I’m saying, I don’t have to listen to what other people’s opinions are,” he adds.

Stevens points to a dark period in Vermont’s history as proof of his own indigeneity.

“So, if you look at my great great grandfather Antoine Phillips, it clearly states that Antoine had French and Indian blood in the eugenics records,” says Stevens, pointing to a highlighted section of the records in question.

“My family was one of the targets of this eugenics, which is public record and the only reason why I’m sharing this,” Stevens adds.

In the early 20th century eugenics was a practice concerned with so-called improving the gene pool of humanity. To achieve this, eugenicists sometimes encouraged techniques such as forced sterilization.

Nowadays eugenics is widely considered unethical and racist, and Stevens says the movement is a reason why there was little to no public record of Abenaki communities in Vermont from the early 20th century until the 1970’s.

“Did we all intermix? Yeah. I mean people intermarried, but when you say hiding, I’m just saying we worked within our groups and we worked along our family units and we weren’t out there parading around,” says Stevens. “People wonder why people go into hiding or they’re not very vocal about it. Look what’s happening today. We’re under attack today just like our ancestors were under attack previously. The difference is they were being sterilized.”

Stevens says that his grandmother went to great lengths to hide her identity to avoid forced sterilization.

“She was born as Lilllan-May and she got married as Pauline and died as Delia because she was affected. My uncle even mentioned that she went to live with an aunt of hers to avoid it in DC,” says Stevens.

But some say public records from that era tell a different tale.

“I’ve never seen any big smoking gun file where the eugenic survey or the law targeted Native Americans or Abenaki,” says Richard Witting, a Master’s student of history at the University of Vermont. “I see nothing that says that, right, because at the time the state of Vermont didn’t believe there were any Abenaki here. And that holds true from the founding [of Vermont] to you know, the 1960s.”

Witting’s thesis is researching people who were sterilized as a result of the Vermont eugenics movement. He says he’s seen brief references to Indigenous ancestry in only a few records that discussed surveillance, and that none of the 44 sterilized people whose names that have been made public could be classified as Abenaki in terms of genealogy.

“I think we should see the eugenics survey and sterilization law as a really terrible time in Vermont history, but to imagine it as a genocide against Indigenous people who are Abenaki is, I feel, really repurposing the story to do something else,” says Witting.

Witting’s research suggests that the law mainly targeted the poor using outdated clinical diagnoses such as “imbecile” and “feebleminded” that would now be considered vague and offensive.

However, Witting says that there is evidence some family members of Vermont-recognized Abenaki groups may have been surveyed for possible sterilization…but not because they were Abenaki.

“If you were a poor French Canadian in Vermont, you were more likely to be in these institutions in the eugenic survey,” says Witting.

However, of the 256 documented people who were sterilized over three decades, more than 200 of them have yet to be identified due to Vermont privacy laws.

The state of Vermont has apologized for its role in the eugenics movement, although the 2019 resolution uses some verbal gymnastics, saying they apologize to: “…persons whose extended families’ successor generations now identify as Abenaki.”

Meanwhile, the state governor, Phil Scott, has declined to meet with Odanak.

Jacques Watso says if nothing else, the state should rescind recognition for its own citizen’s sake.

“They are claiming history that is not theirs and it’s very frustrating because a lot of people are trying to do good. The white settlers are trying to do good with the past and trying to heal this past and these individuals they took our place in history,” says Watso.

The four state recognized Abenaki groups receive property tax breaks. They are allowed to market arts and crafts as Indigenous made, and they have several registered charities, some with budgets in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Stevens says it isn’t a lot of money when considering it’s earmarked for services for several thousand people.

“We get our funds, if we get them, from donations and grants that are here, which are eligible for any nonprofit who applies for them. We don’t have a stipend that they, the government, pays us for being chief like they do in Canada, you know, where they give them a certain amount every year. We don’t get that,” explains Stevens.

Stevens may have had his Abenaki ancestry called into question, but spend any time with him and it’s clear he is knowledgeable in Abenaki culture and lore.

The Vermont recognized Abenaki groups are celebrated by the state with numerous cultural festivities, and are lauded for their work in Abenaki language preservation.

But Odanak community members like Suzie O’Bomsawin are concerned about what this means for the future of Abenaki culture.

“It’s kind of like really uncomfortable to be here today and see that they [Vermont recognized Abenaki] are becoming the reference of our culture in Vermont and elsewhere, they are publishing books and stuff like that. So, it’s getting to be their culture, like it’s their own now and I struggle with the fact that if we don’t fight what’s happening right now, my children will have to have that battle over time,” she says.

She also points to the fact that Abenaki from Odanak never stopped going to Vermont.

From 1870-1920 Abenaki black ash baskets were a huge part of Odanak’s economy, allowing them to offset the loss of hunting land to encroaching settlers.

Many of the best customers were Americans on holiday in New England, giving Abenaki in Quebec a reason to keep in touch with their ancestral lands by returning every summer to make sales.

“These people [selling baskets] always came back to the community over wintertime,” says Suzie O’Bomsawin. “They were telling stories in the community. They were sharing what happened. They were telling [stories] like, oh I met that family or that other family.”

O’Bomsawin says the Odanak basket trade raises a question: if there were Abenaki groups in Vermont the whole time, why didn’t they connect with basket makers from Odanak?

“At no point in time, or very on rare occasion did they say that they met people they didn’t know on the territory that were speaking Abenaki or that were referring to themselves as Abenaki,” says Suzie.

The state of Vermont has not responded to our interview requests regarding recognition of the four Vermont groups.

However, an access to information request shows that the state did leave the door open a crack for Odanak, by recommending they speak with both their house and senate about the recognition question.

“We’re only asking for those rights to go to those who rightfully deserve it. That’s all we’re asking,” says Odanak Chief Rick O’Bomsawin.

Several independently done genealogies by other media appear to show that Don Stevens has no Abenaki ancestry. A genealogist that APTN consulted says that Stevens has a distant First Nation ancestor who is not Abenaki.

But to say he and other Vermont recognized Abenaki have no Indigenous allies would be wrong.

In the past, members of the Wolastoqiyik nation have expressed support, and others say Odanak is putting too much emphasis on blood quantum.

“To me it comes down to a very simple argument which is a little bit terrifying and the argument is that being Indigenous is a bit like having a credit card or a can of Campbell’s soup, it has an expiration date on it,” says Randy Kritkausky, a retired academic and author who wrote a book about rediscovering his Native American roots.

An enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Kritkausky now advocates for environmental issues and splits his time between Vermont and Montreal. He has been an outspoken advocate of the Vermont recognized Abenaki, saying that culture isn’t necessarily taught, but lies within.

“Ancestral memory, cultural memory can re-emerge. I’ll give you a biological analogy, monarch butterflies leave California, they fly south, take some two generations to get where they’re going. Three generations down, they come back to the exact same place. They don’t have a GPS system. They don’t have anything other than something that got imprinted in their DNA,” explains Kritkausky.

Others say Kritkausky is pushing the limits of logic.

“Well, you can only water down a glass of milk so much until you got a glass of water. That’s native ancestry,” says Chief O’Bomsawin.

That being said, Chief O’Bomsawin is attempting to cool down the heated rhetoric around the debate.

This past spring, he invited the leaders of the Vermont-recognized Abenaki to have a meeting in Odanak.

“I’m not denying any of them. I’ve only asked whose family they’re part of, and if they are part of our families, we will welcome them with open arms,” says Chief O’Bomsawin.

To date, no meeting has been arranged, but Rich Holschuh says he’s open to the idea

“I trust that there can be a restoration of relationship there,” says Holschuh. “I think it needs to be conducted on equal terms in a place that everyone agrees to, dynamics being what they are right now.”

When he’s not working to build Abenaki cultural centres, Holschuh is chair of the government-appointed Vermont Commission of Native American Affairs.

But not without some controversy.

From a genealogy perspective, Holschuh’s Indigenous ancestry is distant. When questioned, he said he is related to the Abenaki through “kinship.”

Holschuh says he doesn’t dismiss the work of people like Leroux and Witting as invalid but rather sees them as “working within a constructed framework of colonial recognition.”

“Traditional teachings as I have been taught and as I am learning show a very different way to be in the world. It’s not about locking knowledge down in black and white, somebody says this and someone says that all experiences are valid, all realities are valid. There are multiple realities,” says Holschuh, who pauses to smile before adding “It’s a very freeing way to be in the world.”

The idea of multiple realities seems to be gaining ground in the internet era.

One reality: Vermont recognized Abenaki work hard to preserve language, share culture, and even have food banks for the less fortunate.

Another possible reality: they have used claims of indigeneity to obtain hundreds of thousands of dollars, tax breaks, and cultural cachet.

Perhaps those realities themselves aren’t so important as to who gets to decide the future of the people of the dawn.

Editor’s Note about Don Stevens’s ancestry.

With regard to his Abenaki ancestry, there are some details that require further explanation. According to Quebec archives, there is a deed of sale from 1664 that describes his ancestor, Marie-Olivier Sylvestre, as Algonquin. Sylvestre was born around 1624 to a mother, Outchibahabanoukoueou, and a father, Roch Manitouabeouich, both of whose origins have been called into question. Manitouabeouich is often considered Algonquin or sometimes Huron-Wendat, however, The Algonquin Nation Secretariat (who represent three Algonquin First Nations in Quebec) says that Roch Manitouabeouich was “likely Abenaki.” Some places list Sylvestre’s mother as unknown, others say Outchibahabanoukoueou was an Algonquin name, while some sources say she was born in an Abenaki village. It is also worth mentioning that Abenaki is part of the Algonquin linguistic tree, and it is unknown how well Europeans in the 1600’s were able to differentiate between the eight First Nations in Quebec that speak an Algonquin-rooted language. Whether she was of Abenaki, Huron-Wendat, or Algonquin origin, Marie-Olivier Sylvestre is thought to be the first Indigenous person in Canada to marry a European and it is estimated that she has 800,000 descendants spread out over 13 generations. With regards to Don Stevens’s ancestry, in addition to Marie Sylvestre and his great-great-grandfather Antoine Phillips listed in the Eugenics records (previously discussed in this story), there is also mention of a Delia Bone, said to be “part Indian and part French…from an Indian reservation near Montreal” that married his great grandfather Peter (son of Antoine).