Seamus O’Regan is marking World Water Day with a tip of the hat to the Liberals’ work on eliminating long-term boil water advisories in First Nations communities.

“Everyone should have access to safe, clean, and reliable drinking water,” the Indigenous Services minister said in a statement released Friday. “Today, on World Water Day, we reflect on the progress that has been made toward that goal, both in Canada and around the world, and acknowledge the important work still ahead.”

The Trudeau government has pledged more than $2 billion to lift all long-term drinking water advisories on reserves. To date, 81 of those advisories have been lifted, while 59 remain.

But while the government is noting its achievements this March 22, a leading human rights organization is using the occasion to highlight federal government policies and resource development projects that harm Indigenous communities’ water and contribute to environmental racism in Canada.

“Far too often, governments in Canada have demonstrated that they place little value on the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples and the revitalization of their cultures and traditions,” Tara Scurr, business and human rights campaigner with Amnesty International Canada, said in a statement Thursday.

“That’s why we are marking World Water Day by renewing our commitment to support the Indigenous water defenders leading these crucial and inspiring human rights struggles.”

Amnesty says the 2014 Mount Polley mine disaster in British Columbia, the ongoing harmful impacts of industrial pollution at Grassy Narrows, and the construction of the Site C dam in B.C.’s Peace Valley all represent instances of environmental racism and threats to fresh water.

In August 2014 the collapse of a tailings pond at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley copper and gold mine sent roughly 25 million cubic metres of water and toxic mining waste into Quesnel Lake and other nearby waterways, where Amnesty says up to 25 percent of salmon in B.C. return to spawn each year.

The long-term and full impacts of the 2014 Mount Polley mining disaster in Secwepemc territory is not yet known. File photo.

On unneeded Secwepemc territory, the event represented the worst mining disaster in Canada’s history.

“The loss of the salmon, for us as Secwepemc, is a matter of life or death for our culture,” Secwepemc Elder Jean Williams has said.

Almost five years later, charges have yet to be laid and locals are still fighting a discharge permit that allows Imperial Metals to dump 10 million cubic metres of treated mining effluent into Quesnel Lake, even though the impacts of the 2014 disaster are not yet fully known.

“We have already lost access to our land, traditional foods and medicines,” says former Xat’sull First Nation Chief Bev Sellars, who fight and lost a case against Imperial Metals subsidiary Mount Polley Mining Corporation, which operates the mine.

“We can’t afford to sit back and watch more toxic waste being dumped into our sacred waterways.”

Meanwhile, several hundred kilometres north, First Nations say the Site C hydroelectric dam threatens fresh water, fish and their communities’ livelihoods in the Peace Valley.

In December the United Nations’ Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (UNCERD) wrote a letter to Canada’s ambassador to the U.N., Rosemary McCarney, calling on the federal government to halt work on the controversial dam pending the outcome of a First Nations-led legal challenge to the project.

“The Committee is concerned about the alleged lack of measures taken to ensure the right to consultation and free, prior and informed consent with regard to the Site C dam, considering its impact on indigenous peoples control and use of their lands and natural resources,” CERD Chair Noureddine Amir wrote in the Dec. 14, 2018 letter.

The Prophet River and West Moberly First Nations launched a treaty rights challenge against the project in January 2018.

The two Treaty 8 Dane-zaa Nations also applied for an injunction to stop work on the project in order to protect 13 site of cultural importance, but were rejected by a B.C. Supreme Court judge last October.

Justice Warren Milman said in his ruling, however, that the treaty challenge trial be concluded by 2023, prior to the earliest possible date for reservoir flooding on the Peace River.

West Moberly Chief Roland Willson has called Site C’s impacts cultural genocide.

In Thursday’s Amnesty release he says his people are already “living with the harm caused by previous dams on the Peace River and now the B.C. government wants to take away some of the most critical cultural and ecological areas that are left for us.

“There’s a good reason that this project has been condemned by the UN’s top anti-racism body. The only question now is whether the federal and provincial governments will listen and act.”

CERD has given the provincial and federal governments until April 9 to show what it’s doing to halt construction of the $10.7 billion project.

“It is the responsibility of resource development companies to respect human rights – and for our governments to swiftly act when they do not,” Amnesty said in its statement Thursday.

Amnesty calls Site C a “planned disaster,” the Mount Polley mine disaster a “preventable disaster,” and the mercury poisoning in Grassy Narrows “a disaster ignored.”

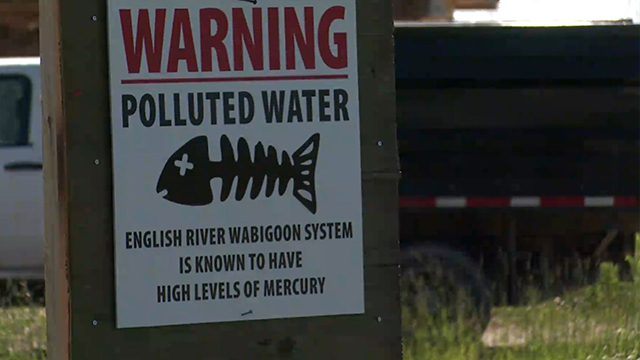

A health study released last year links the effluent dumped by the operators of a mill in Dryden, Ont. into the English and Wabigoon river systems in the 1960s and ‘70s to a multitude of physical and mental health illnesses and conditions.

“Despite the impacts on our community of decades of mercury poisoning, our incredible children and youth have demonstrated their resilience by drawing so much public attention to our struggle,” Grassy Narrows First Nation Chief Rudy Turtle says in Thursday’s release.

“We need Prime Minister Trudeau to do everything in his power to join us in preventing more generations from bearing the brunt of this environmental crisis.”

“It’s no coincidence that three of our highest priority human rights cases in Canada all revolve around contamination and threats to the rivers and lakes on which Indigenous peoples depend for their livelihoods and ways of life,” Scurr says.

Amnesty says “it is the responsibility of resource development companies to respect human rights – and for our governments to swiftly act when they do not.”